[ad_1]

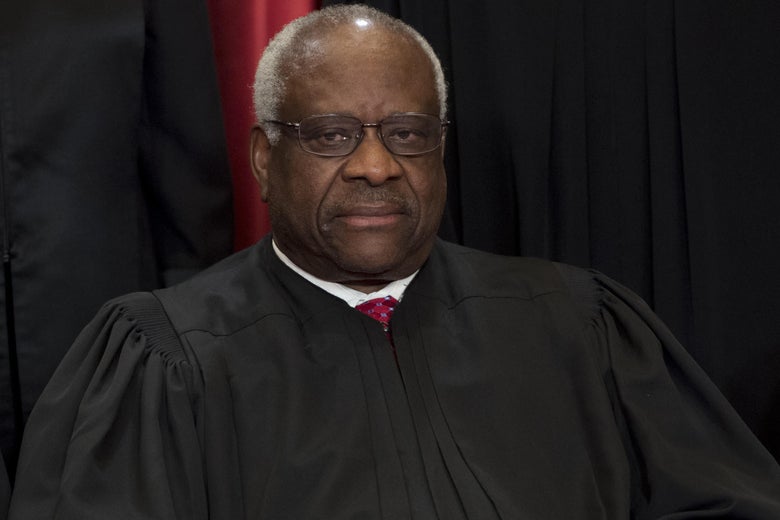

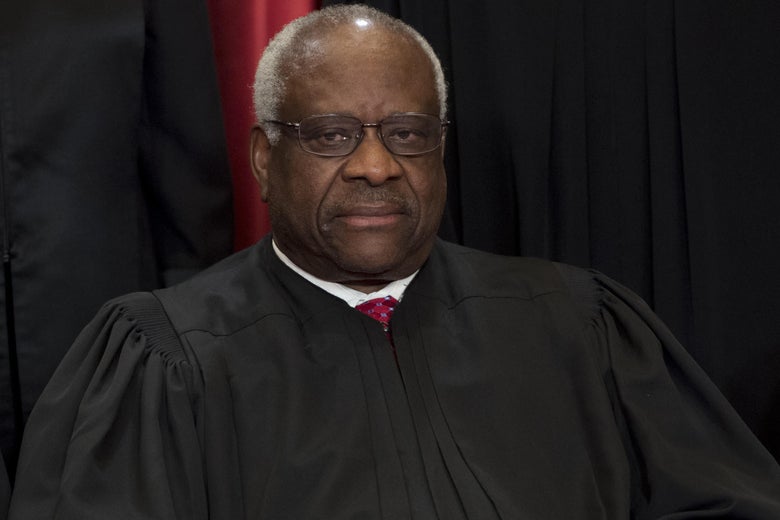

Judge Clarence Thomas sits for an official photo with other members of the Supreme Court in Washington on June 1, 2017.

Saul Loeb / Getty Images

In a 5-4 decision Tuesday in NIFLA c. Becerra, the US Supreme Court upheld the challenge of a 2015 California law that required California reproductive health clinics to provide certain information to clients. The court, in an opinion written by Judge Clarence Thomas, concluded that the Freedom of Reproduction, Liability, Comprehensive Care and Transparency Act, the FACT Act, was likely to violate the First Amendment and remanded the case before the lower courts for reconsideration. This represents a great loss for states trying to inform women of the full range of their reproductive options.

The FACT Act was promulgated in response to the emergence of crisis-affected pregnancy centers, often with religious affiliations, which presented themselves as comprehensive reproductive health clinics but opposed abortion and often provided pregnant women with inaccurate or misleading information about their options. The law provided for two sets of requirements: licensed clinics were to post notices to inform their patients that free or low-cost abortions were available in the state, and they had to provide the phone number of the public agencies can connect women to providers. Unauthorized centers were required to post disclaimers in their advertisements to specify, in up to 13 languages, that their services do not include authorized medical assistance. The clinics went on to argue that the law violated the first amendment. On Wednesday, the Supreme Court stated that they would probably override this claim.

Clarence Thomas, writing for the five conservative judges in the majority, found that these required opinions constitute a content-based regulation of speech. He notes that since the services must provide information on abortion – "the very practice that petitioners are bound to oppose" – the licensed notice "clearly modifies the content" of the speeches of the petitioners. He writes that the court does not have a special status for "professional speech" and that "the opinion at issue here is not a requirement of informed consent or any other regulation of professional conduct. By applying a "strict review" to the notice requirement – the highest level of judicial review – he finds the law inadmissible. Thomas goes on to note that while California's interest is in "educating low-income women about the services it provides, then the license notice is extremely sub-exclusive" , noting that many clinics are excluded from the requirements.

Justice Anthony Kennedy has written a distinct and dramatic agreement that strives to accuse California lawmakers of targeting these clinics "because of their beliefs". In a paragraph that deserves to be quoted in full, he writes that this is the mark of totalitarian governments:

The California Legislature has included in its official history the congratulatory statement that the law was part of California's "vanguard" legacy. App. 38-39. But it is not avant-garde to force individuals to "be an instrument to promote public acceptance from an ideological point of view." [they] fin[d] unacceptable. ") It is avant-garde to begin by reading the first amendment as ratified in 1791, to understand the history of the authoritarian government as the Founders knew then, to confirm that history shows since then to how relentless authoritarian regimes attempt to stifle freedom of expression, and pursue these lessons by seeking to preserve and teach the need for freedom of speech for future generations. be allowed to force people to express a message contrary to their deepest convictions Freedom of expression guarantees freedom of thought and belief This law endangers these freedoms.

In a dissenting opinion that he read, Judge Stephen Breyer notes that the majority approach targets virtually all disclosures required by professionals:

Because many, perhaps most, human behavior goes through the discourse and that many, perhaps most, regulates this speech in terms of content, the approach of the majority threatens at least the constitutional challenge of A good deal of government regulation. . Virtually all disclosure laws could be considered "content-based" because virtually all disclosure laws require that people "speak a particular message".

He goes on to observe that there are long-standing laws that regulate reproductive health disclosures and notes that "if a state can legally require that a doctor ask a woman to seek an abortion about adoption services, why could not it, as here? to ask a medical advisor to tell a woman who is seeking prenatal care or other reproductive health care about the services available to her. Childbirth and Abortion? "As he noted during the oral argument," the rule of law embodies uniformity ". gander. & # 39; "

Breyer concludes by pointing out that the majority seems to assume that the professional discourse on abortion is special, that it involves in this case not only professional medical issues, but also opinions based on deeply held religious and moral beliefs anchored in the nature of the practice He adds that this is one more reason for "interpreting American constitutional law so that it applies equitably within a nation whose citizens have strongly these different points of view.

Breyer seems hoping that this decision will invalidate the many state laws that force doctors – over and above their objections and medical reality – to warn women that their risk of suicide, breast cancer and depression will increase if they have an abortion. Judge Kennedy's agreement suggests that these misleading warnings are not a problem. But when the state demands that religious believers tell the truth, says Kennedy, it is authoritarianism.

Source link