[ad_1]

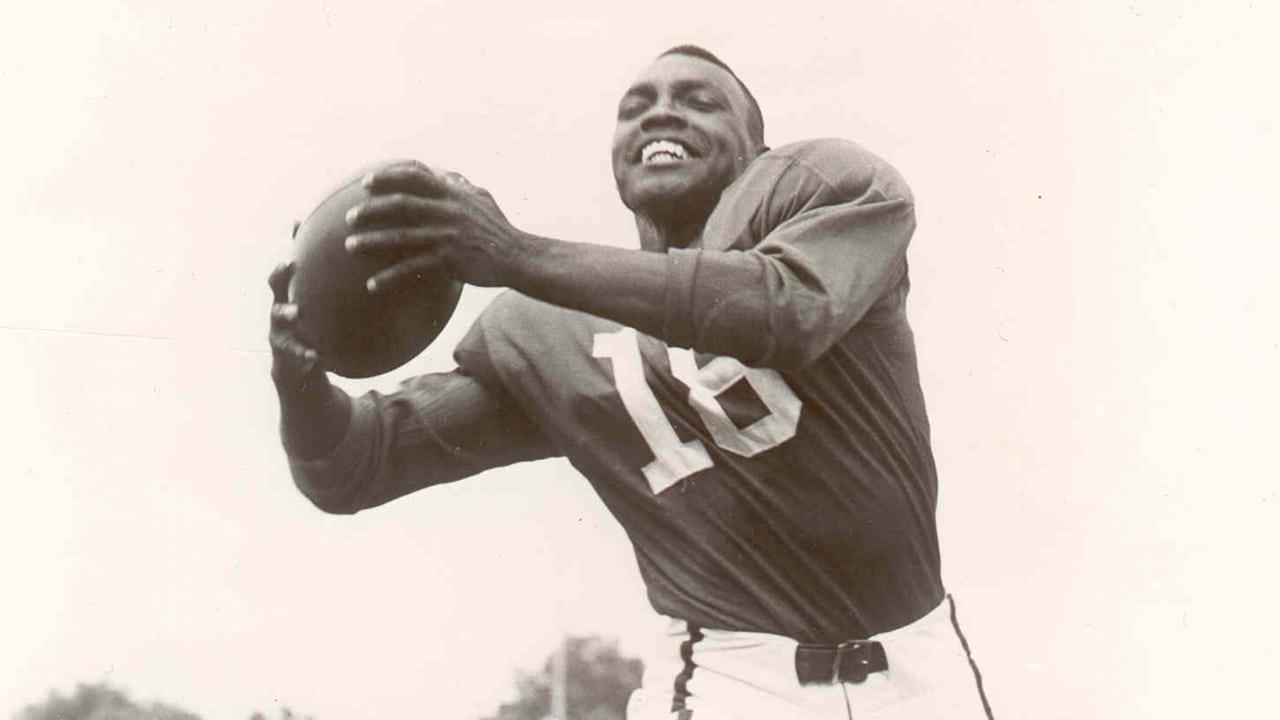

Wally Triplett’s impact on football and his place in the game’s history will be measured by more than the yards he gained and the length of his career.

Triplett was a running back and record-breaking return specialist on the field for the Detroit Lions and a pace-setter and historical barrier breaker in a period of racial segregation.

Triplett and others of his era opened the way for generations of African American players who followed the path to the National Football League.

Triplett, who began his NFL career as a rookie drafted by the Lions in 1949, passed away on Thursday, Nov 8, after a long illness. He was 92 and had been a long-time Metro Detroit resident.

Football was a different game in Triplett’s era, and not just because of roster sizes, helmets without face masks and domed stadiums with artificial playing surfaces.

Before he got to the NFL, Triplett faced blatant racial prejudice that was standard operating procedure, without fear of retribution or rebuke. The color line was guarded in some parts as fiercely as the goal line, until Triplett and others of his era crossed through it.

Triplett became the first African American drafted by the Lions when they took him in the 19th round in 1949 after a successful career at Penn State.

The 1949 draft class represented a culture change for the NFL. Three African Americans were drafted that year, the first in NFL history.

Triplett was the third, but he had the distinction of being the first African American draft pick to play in a regular-season game. George Taliaferro, a 13th-round pick by the Chicago Bears, was the first drafted.

Triplett spent two seasons with the Lions, 1949-50, as a running back and return specialist.

Triplett’s 1950 season, and his career, were interrupted when he was drafted into the Army on Nov. 15. He played seven of the 12 games that season. He served two years during the Korean War, missing all of the 1951 season.

He returned in 1952 and was traded to the Cardinals, then playing in Chicago, where he played his last two seasons.

He was a teacher and successful business man after the end of his playing career.

Triplett grew up in the Philadelphia suburb of La Mott, where he was an outstanding high school player. He was in high demand by college recruiters. The University of Miami (Fla.) offered him a scholarship, without having seen him play in person. The offer was withdrawn after it was learned that he was black.

Triplett went on to play at Penn State, where he got an academic scholarship, and entered school in the fall of 1945. In 1948 Triplett became the first African American to play in the Cotton Bowl. He caught the tying touchdown in a 13-13 tie with Southern Methodist.

When Triplett got to the Lions in 1949, Bob Mann already had broken the color barrier. The former University of Michigan star had made history as the franchise’s first African American player when he signed as an undrafted free agent in 1948 and made the roster.

Mann played seven NFL seasons as a wide receiver – the first two with the Lions and the last five with the Packers. As a Lion, Mann led the NFL in receiving yards with 1,014 in a 12-game season in 1949.

At 5-11 and 173 pounds, Triplett was slightly built, but his size did not hold him back in his primary role as a return man on punts and kickoffs.

He played 11 games with five starts in 1949 and rushed for 221 yards on 53 carries with a long run of 80 yards. He averaged 4.2 yards per carry and scored one touchdown. It was his best season as a runner.

As a return man, it was another matter. In Game 7 of 1950 against the Rams at historic L.A. Coliseum he set a franchise record for return yards that still stands.

Triplett returned four kickoffs for 294 yards – an average 73.5 yards per return. He had a 97-yard touchdown return and two other returns of 74 and 81 yards.

Triplett’s performance held up as the league record until it was surpassed in 1994, and again in 2009.

It remains the longest single-game individual record in the history of the Detroit Lions franchise.

Like his kickoff return record, Triplett’s legacy and historical impact have stood the test of time.

Source link