[ad_1]

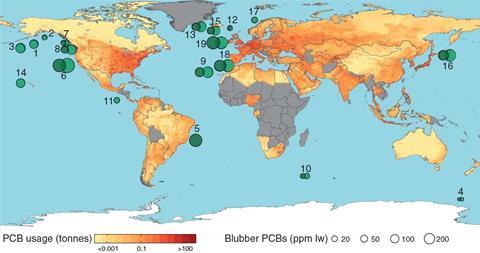

The survival of more than half of the killer whales in the world is at stake because of a very persistent and toxic class of chemicals. Despite an almost total ban on the production of polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) 30 years ago, these carcinogenic and reproductive toxins persist in the environment.

A new study of the effects of PCBs on these major marine predators over the next 100 years has revealed that many populations may decline – and some may even collapse completely in some areas.1

"The killer whale can absorb these compounds, but their metabolic system is not ideal for eliminating them," says lead author Jean-Pierre Desforges of the Arctic Research Center at Aarhus University in Denmark. & # 39; For [PCBs] do not decompose very quickly in the environment, they tend to accumulate in these animals throughout their lives. "

PCBs are organochlorine compounds that were first marketed in 1929 and then used in a variety of products during the 20th century, including electrical equipment, carbonless paper, and pigments and dyes. Once recognized the environmental hazards and carcinogenic nature of PCBs, they were banned in the United States in 1979 with other bans introduced around the world.

Today, however, PCBs persist worldwide, even in remote areas far from their manufacture. This is because these chemicals resist most forms of degradation, have a long half-life and low solubility in water that allows them to circulate freely in the world's oceans. It is estimated that few countries will achieve their goals of ceasing the proper use and disposal of PCB-containing equipment over the next 10 years under the Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants.2

The persistence of PCBs and the extent of contamination of the world's oceans have led to their accumulation in so many killer whales, as described by Bert van Bavel of the Norwegian Institute for Water Research as "an optimal cocktail. ". As killer whales are at the top of the food chain, they are among the most PCB-contaminated animals as a result of feeding contaminated fish and marine mammals. Their fat is also well adapted to the binding of the chemical, further concentrating the PCB levels.

"This is one of the first long-term PCB risk assessments," notes van Bavel, who was not involved in this work. "These are rough estimates and future scenarios are much less certain … but it tells us what we should do in terms of legislation."

Desforges and his collaborators predict that killer whale populations around industrial areas that once produced large amounts of PCBs, including the United Kingdom, Japan and Brazil, may disappear. "PCB levels are so high in these populations that we suspect there is large-scale reproductive failure," says Desforges. "As older animals die, there will be no new life to replace them … and there will probably be a significant immunosuppression that will expose them to more death." He adds that these two factors are responsible for the majority of PCB toxicity in killer whales. "What we hope to show in this study is that this problem has not disappeared and we still have to do more."

[ad_2]

Source link