[ad_1]

One of the benefits of working in a university with an agricultural school is the availability of meat. This is especially useful if you need something to stab the cactus spines.

Scientists were not as interested in meat as in determining the relationship between the structure of a cactus spine and the quality of its striking and anchoring inside the perforated thing. More generally, they hope to understand why cactuses develop different spines and, more generally, how the forms of thorns in nature, from one species to another, may depend on their functions.

And some thorns were really good at doing their job. "A spine really impressed us with the tenacity with which it clung," Stephanie Crofts, the author of the University of Illinois study, told Gizmodo.

Scientists first collected five spines from six cacti specimens. They performed tests to measure the force required to puncture the target material and determine the degree of compression of the spine on the surface of the material before drilling. They first perforated a laboratory grade polymer, but then wanted to work with something more biologically relevant. So they bought pork from the university's school of agriculture and store-bought chicken, Crofts said.

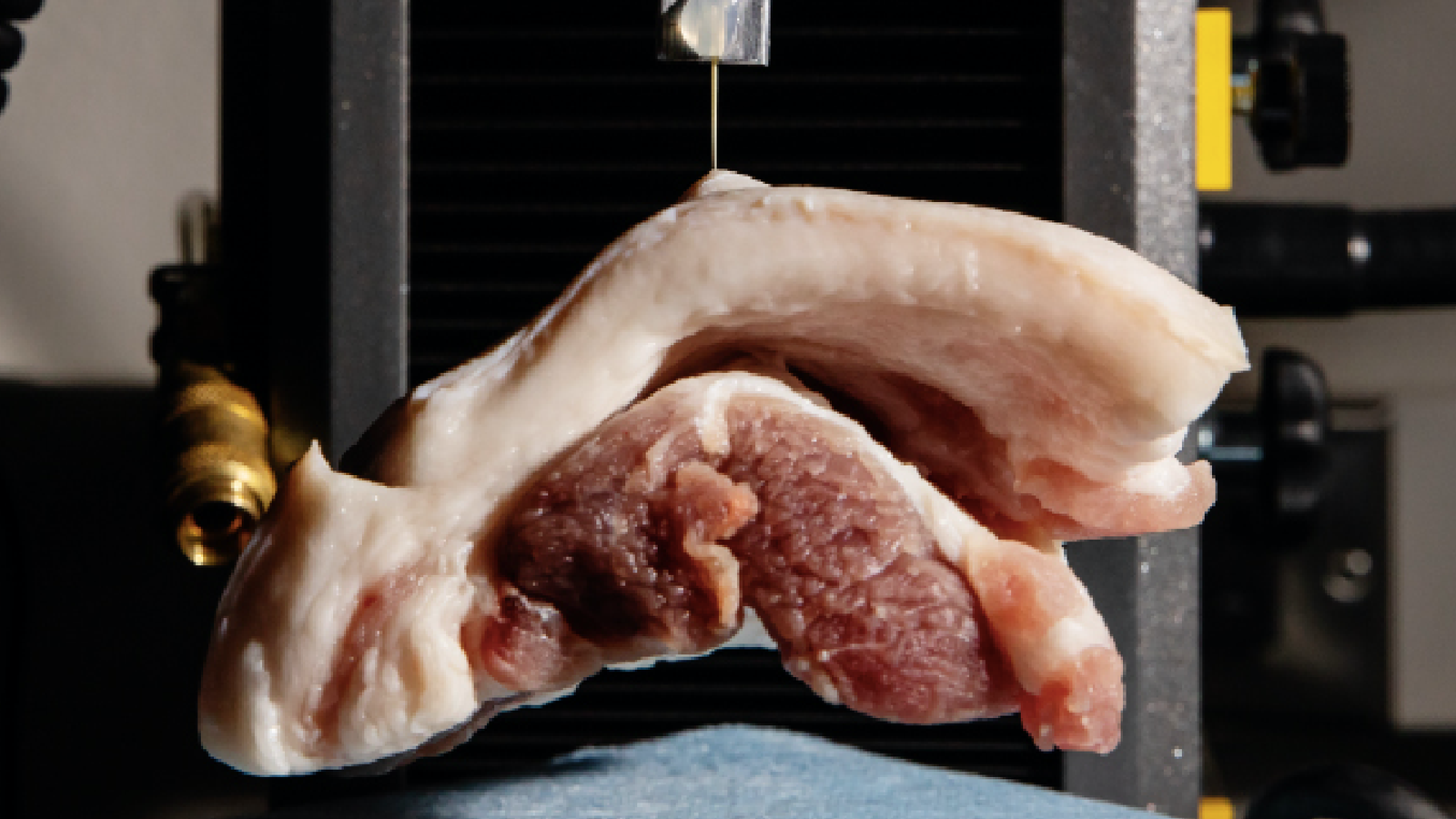

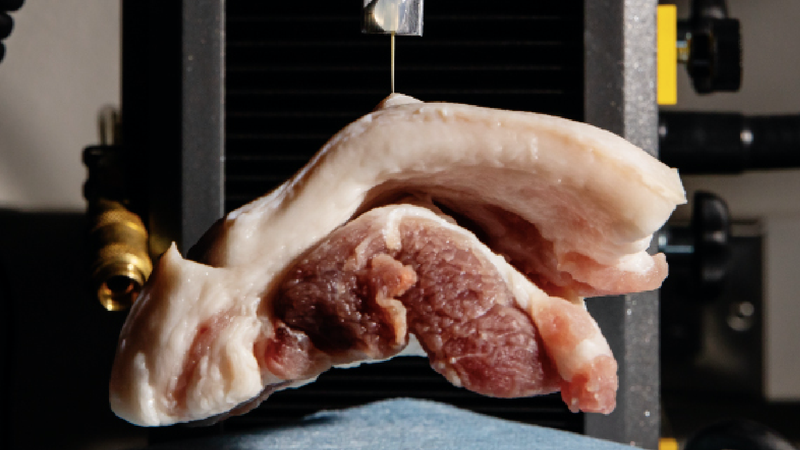

According to the study published in the Acts of the Royal Society B, thorns varied in their piercing abilities, but it turned out that barbed thorns put much less force in drilling a hole in a surface than unbarbed thorns. the barbed spines remained anchored. The spine of the jumping cactus even raised a pork plate half a pound from the work surface, forcing scientists to remove the meat.

Why should a spine be so thorny? Well, since new cacti can grow from some parts of the jumping cholla that come off, called cladodes, thorns that remain firmly attached to an unlucky passerby have a benefit in terms of evolution. And unlike animals with sharp parts, cacti can not decide who gets stung.

However, this laboratory at the University of Illinois is studying all kinds of pokers. Porcupines, for example, similarly have barbed spines, demonstrating that both seem to have evolved to perforate easily and remain housed within a victim. And it is wild enough to think of how two extremely different species belonging to different realms can evolve in the same way.

"The search for these systems gives us the opportunity to compare evolution and biomechanics both in plants and in animals," said Gizmodo's Phil Anderson, author of the study and assistant professor in animal biology. "You do not often have the chance to make a direct comparison like this."

It's more than just understanding animals. You have probably already heard of the use of gecko feet or octopus cupping to create a bio-inspired technology for humans. The study of a series of spines could allow engineers to develop the ideal machine for stabilizers and scales.

The study does not comprehensively examine cactus spines and researchers have other avenues to explore. But this gives an idea of why cactuses develop thorns.

But more importantly, pay attention to how you carry meat when you walk near a jumping cactus.

[Proceedings B]Source link