[ad_1]

In recent years, doctors have explored an unorthodox way to treat cases of depression that have not responded to other treatments: send precise electric shocks directly to the areas of a patient's brain, also called Deep brain stimulation (DBS). Although the technique has been promising, its positive effects tend to be inconsistent.

But a new study from the University of California at San Francisco, published Thursday in Current Biology, seems to offer some interesting progress for DBS as a treatment for depression. Their research suggests that there is another possible target for stimulation, one that could provide more reliable improvements in mood. Better still, the new target could be released from the disturbing side effects seen with traditional DBS, like mania.

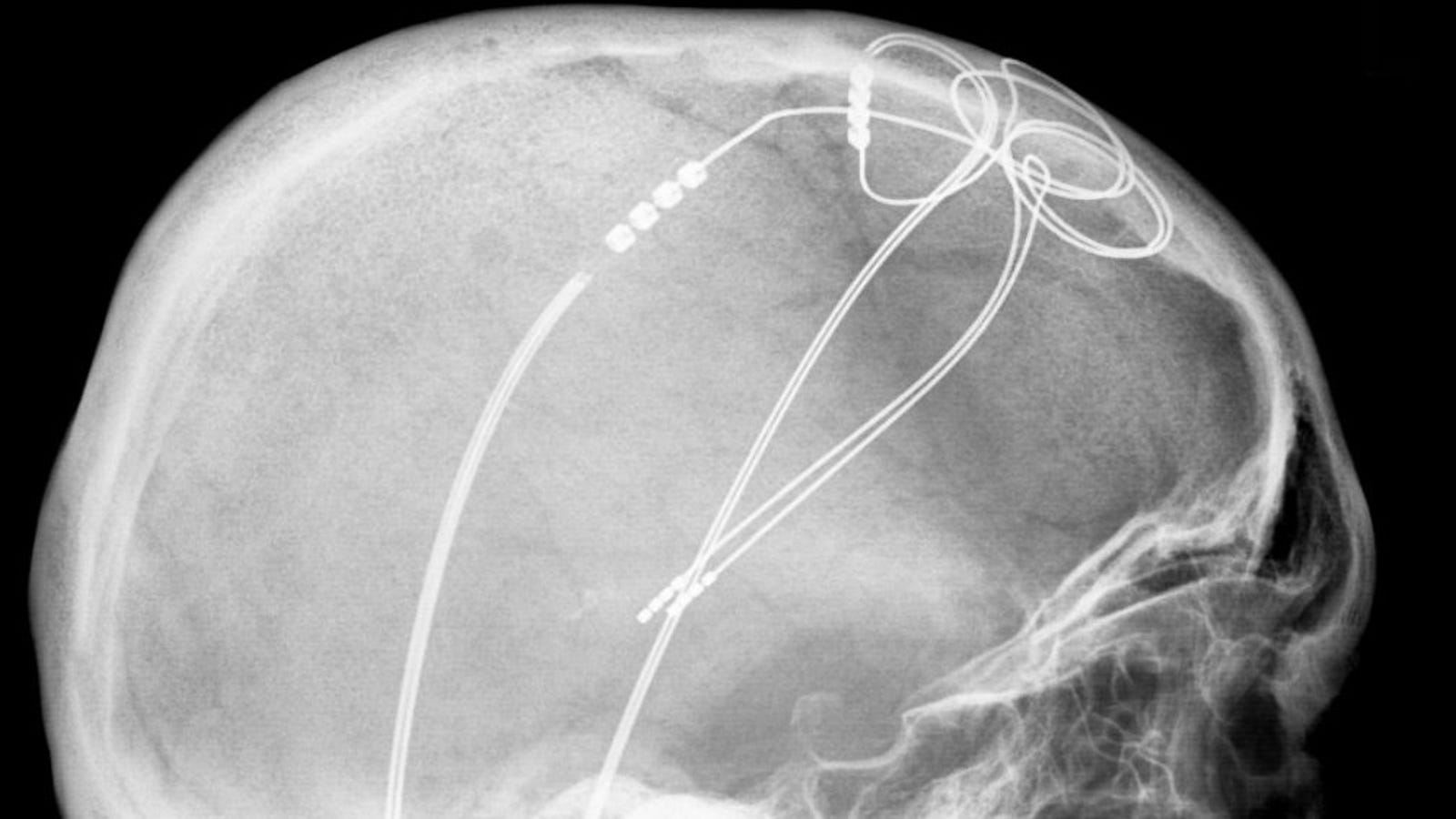

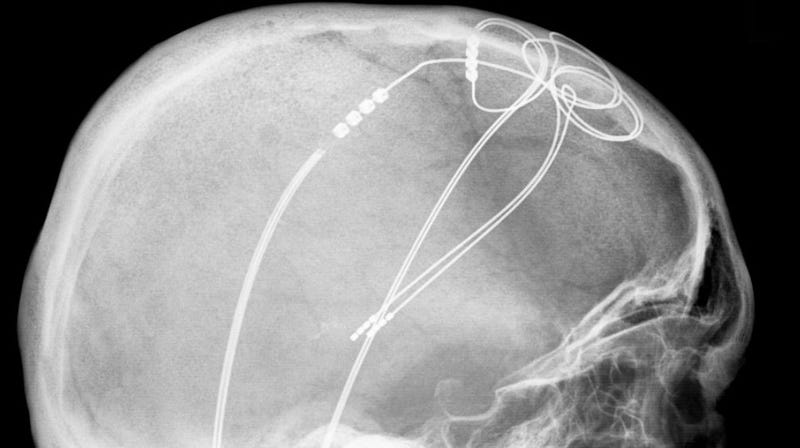

DBS is commonly used to manage neurological conditions such as Parkinson's disease and seizures. These conditions are characterized by irregular electrical activity in certain brain regions, and pulses used in DBS – sent via electrodes implanted into the brain via surgery and controlled by a device also implanted in the body elsewhere – are thought to act as a pacemaker, temporarily restoring a healthy brain pattern and relieving symptoms. People with depression also tend to have abnormal brain activity. It was therefore assumed that DBS could be useful in difficult cases of depression.

The researchers behind this study had the opportunity to conduct a unique experiment. They were able to study 25 patients with chronic epilepsy who planned to undergo surgery that would temporarily implant electrodes into their brains. Implants allowed doctors to know where the patient's brain seizures came from by recording the local neural activity of a targeted area of the brain (locating the seizures, doctors could then plan safe removal of the parts affected by the disease). the brain later). But for their experience, the researchers were able to use these same implants to essentially imitate a DBS session.

Patients had implants placed in various areas of the brain, including near the lateral portion of the orbitofrontal cortex (OFC), a region just behind the eye. OFC is known to play a role in decision making, emotion treatment and mood regulation. And although she is also involved in depression, she has not been studied extensively as a stimulation target.

Over the course of several days, volunteers had different brain regions stimulated via DBS, including OFC. Sometimes patients were given fictitious stimulation, which served as a control. And after each stimulation session, they explained how they felt and answered questionnaires designed to assess their state of mind.

Patients had symptoms ranging from minimal to severe (based on a screening test commonly used prior to surgery). Those who had little or no evidence of depression had no mood swings thereafter, regardless of where the stimulation had occurred or not. However, in people with moderate to severe symptoms of depression, their state of mind was improved only minutes after IOC stimulation. And compared to sessions where other areas of the brain associated with depression were stimulated, these mood improvements appeared to be more reliable, which meant that people experiencing larger shock felt greatly stimulated. .

"Our findings are important as they provide a potential new target for the treatment of mood symptoms through brain stimulation therapies," said Gizmodo, Heather Dawes, co-director of the Emerging Therapeutics-Based Neurotechnology Program. on UCSF systems.

The implants also allowed the researchers to record the brain activity of the patients outside the DBS sessions, which allowed them to better understand what the DBS could have done exactly at the OFC. In particular, the brain activity observed after a patient's sessions seemed to resemble the level of activity observed when the patient was naturally in a good mood.

"This indicates that stimulation can facilitate the natural brain activity underlying a positive mood, rather than inducing a type of abnormal activity," Dawes said.

And it did so without the pendulum turning too far and making patients hyperactive or manic, a side effect sometimes seen with SCP.

Some targets have already been defined for the treatment of depression by SCP, such as the sub-sexual cingulate cortex, a region of the brain usually related to the regulation of emotion and mood. But studies have shown no consistent benefit of DBS treatment. More specifically, a major clinical trial of DBS was completed in early 2013, after an initial analysis that showed that the first wave of patients did not improve as much as expected by the researchers; some people even got worse.

This trial, although technically a failure, did not close the door to DBS treatment. Many patients in the trial who did not respond to PCS in the first six months (the threshold for deciding if the trial should continue to recruit more patients), for example, showed significant improvements in the long-term . And other clinical trials of DBS are already underway. But this led to wondering if there were ways to better refine the treatment.

The OFC theorizes, because it interacts with other areas of the brain that coordinate aspects of mood and emotion, could provide a more consistent benefit when stimulated. There is even limited evidence that non-invasive forms of stimulation (involving electrodes placed on the surface of the head) involving OFC could also help people with depression.

But for now, there is still a lot of work to be done before we can be sure of anything.

"We're really excited about the promising results presented in this article, but there is still a long way to go before it becomes a clinical treatment," Dawes said. This work will include checking whether the same effect can be observed in people who are clinically depressed and who have not responded to other treatments.

"There is also a lot of work to be done to see if this stimulation approach can help patients with depression actually recover from their illness." Until now, we've only been able to look at short-term effects. "she added. "It's an area that we and others will continue to explore."

[Current Biology]