[ad_1]

Residents of the Northern Hemisphere, look up: In the faint flicker of a star above you, astronomers have discovered evidence of an extraterrestrial world.

Researchers say the proposed new planet is unlike anything in our own solar system: larger than the Earth but smaller than Neptune, and far enough away from its dark red sun that any water on its surface is trapped in the ice .

But this frozen "super earth", the second closest exoplanet known to science, is a tantalizing clue to what might be available. And in a not-too-distant day, when telescopes will be able to photograph planets around other stars, it may well be the first new world we see.

"We are moving from science fiction to scientific reality," said Carnegie astronomer Johanna Teske, who contributed to a study of the new planet published in the journal Nature. "There are so many possibilities there."

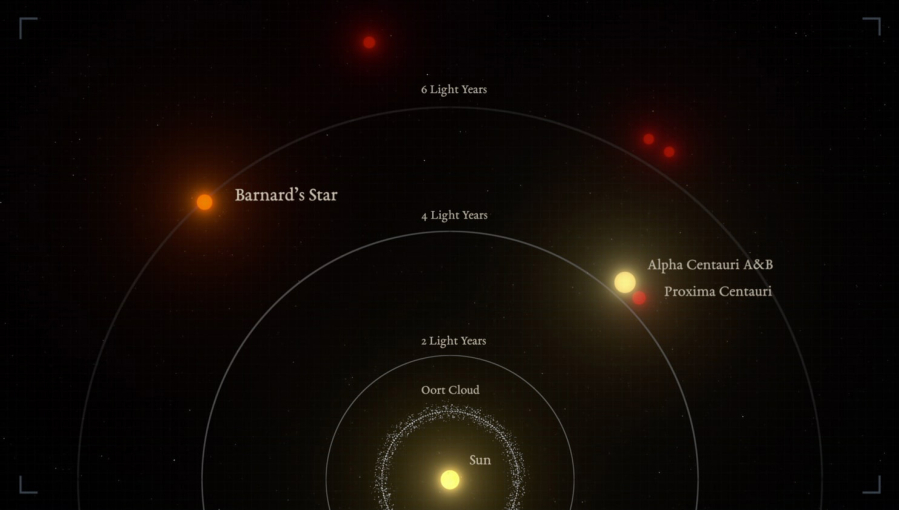

The sun of the exoplanet, a tiny body called Barnard's star, is one of the closest neighbors to our solar system. The only stars closest are the Alpha Centauri triplets, mostly visible in the southern sky. One of these stars, Proxima Centauri, is orbiting a small planet, but the star's tendency to spit out deadly radiation bursts means that its planet will probably not be habitable.

Barnard's star has long been "the great white whale" of the exoplanet hunt, said astronomer Carnegie, Paul Butler, co-author of the document Nature. It's only six light-years away from our sun and maybe twice as much. One of the leading architects of exoplanet research, astronomer Peter van de Kamp, proposed more than 50 years ago that this star could host a planet. In the 1970s, British astronomers studied the possibility of sending an unarmed spacecraft to probe the extraterrestrial system – although it was not proven that there was a planet to explore.

But it was only when the first discovery of exoplanets was confirmed in 1995 that the search for a world around Barnard's Star really began.

This red dwarf is one tenth of the mass of our sun and is too weak to be seen with the naked eye. But its low mass makes it ideal for analysis using the radial velocity exoplanet detection technique, which exploits the way a planet's gravitational pull makes a star wobble when it revolves around the -this.

A series of telescopes on three continents targeted Barnard's Star, allowing researchers to accumulate some 800 observations over a 20-year period. The authors of the study also drew on data collected by amateur astronomers.

It took the combined efforts of more than 50 researchers from nearly twenty institutions, but "slowly, a signal in our data came out of all this noise," said astronomer Ignasi Ribas, director of the Institute of Space Studies of Catalonia, Spain. and the main author of the Nature paper.

The periodic oscillations of Barnard's Star suggest that it is surrounded by a large planet every 233 days. Very few exoplanets have been found so far from their stars (planets with short orbital periods generate more frequent signals, which makes them easier to detect).

Since Barnard's star is so dark, the planet's long orbital period places it on the "snow line", where sunlight is so weak that its surface is permanently frozen. Its average surface temperature is probably minus 238 degrees.

This places the planet outside the traditional "habitable zone", where conditions are supposed to be ripe for life. But Teske pointed out that microbes are resilient creatures. If there is water on the planet and if other necessary ingredients are present, it is possible that organisms are hiding in an ocean under the ice.

Yet many things on the planet around Barnard's star remain uncertain. Astronomers are not sure whether it's rocks like Earth or gas and ice like Neptune. They know that its size must be at least three times larger than the Earth's, but it could be even bigger.

They are not even 100% sure that the planet is there, noted Ribas.

[ad_2]

Source link