[ad_1]

The lawsuits did not do it, the shame of the public did not do it, patients and doctors banded together to "release the data," said Myriad Genetics, a of the oldest genetic testing companies. publishes its proprietary database of BRCA1 variants, which lists more than 17,000 known spelling mistakes in this major "cancer risk" gene, as well as the medical significance of each. The database lists mutations that increase the risk of breast and ovarian cancer, but that do not have any effect on health.

But now, a biology blitzkrieg has hacked the secret cache of life and death data.

By deliberately causing all possible mutations of the type that occur most often in BRCA1 and analyzing the response of cells in the laboratory, researchers at the University of Washington on Wednesday determined the pathogenic and benign mutations. . They also called for more than 2,000 variants with unknown health consequences, an advance that promises to spare thousands of women the anxiety of not knowing whether their BRCA1 variant is a suicide bomb. delay.

The researchers made public their list of variations calls. They urge doctors and genetic counselors to use the results to inform patients, including advising HIV-positive women for a BRCA1 risk variant to consider milestones such as mastectomy and oophorectomy, such as the said Angelina Jolie so well. that they can breathe more easily.

"We are optimistic about the clinical use of these data," said geneticist Jay Shendure of the Brotman Baty Institute of Precision Medicine at the University of Washington School of Medicine, co-leader of the study. "If it was my parent" decide what to do after learning that she had a BRCA1 mutation whose meaning was not clear until now, he said, "I would be at comfortable using this to tip the scales. "

About 12% of women will develop breast cancer, but 72% will inherit a BRCA1 mutation. A little over 1% of women will develop ovarian cancer, but 44% of them will have a harmful BRCA1 mutation. But because there are many genetic and environmental causes of cancer, BRCA1 mutations account for only 5 to 10% of breast cancer diagnoses and 15% of ovarian cancers.

Information on the meaning of BRCA1 variants is known for the most common and for variants whose carcinogenic capacities are unambiguous. It can be found in publicly available BRCA databases, such as ClinVar, managed by the National Institutes of Health, which includes data from individual researchers, Myriad's competitor testing laboratories, and other sources.

For 2,345 "variants of unknown significance" in ClinVar, as well as very rare variants of BRCA1, thousands of women were left in a dilemma. Should they bet that their confusing variant is benign and go about their business, or have life-changing surgery just to be safe?

Myriad has the largest and, it is said, the best source of information. But it is only available to women who receive their $ 3,000 BRCA test, and not the least expensive BRCA tests available on the market since the US Supreme Court invalidated Myriad's genetic patents in 2013.

However, for hundreds of variants, Myriad also does not know the importance of cancer risk. With the new data, said Lea Starita of the Baty Brotman, who co-directed the study, "we can move 90%" of unknown significance variants into public databases "in one way or from another ". "For rare variants, this could be the only data available".

Myriad declined a request for comment. He passed 1 million BRCA tests in 2013.

Dr. Heidi Rehm, a BRCA expert from Harvard Medical School, said clinicians could use data from the Washington group now, calling their approach "well-validated." In almost all cases, the new data is consistent with the existing deleterious data. When she provides new information, categorizing a previously confusing variant as one or the other, she stated that clinicians "should consider" the advice to patients.

NCI's Chanock was more cautious. "It might be tempting to immediately use" the information to interpret the intriguing variants found when women undergo BRCA tests, he wrote, but "this should not be used as a basis for medical advice – at least until To clinical validation. "

This is the gold standard for interpreting variants: whether or not women with a specific variant develop cancer. "But there is not a lot of clinical data, or it's a silo run by Myriad," Starita said.

She and her colleagues therefore sought to understand the consequences of BRCA1 variants by scanning the gene like General Sherman in Georgia.

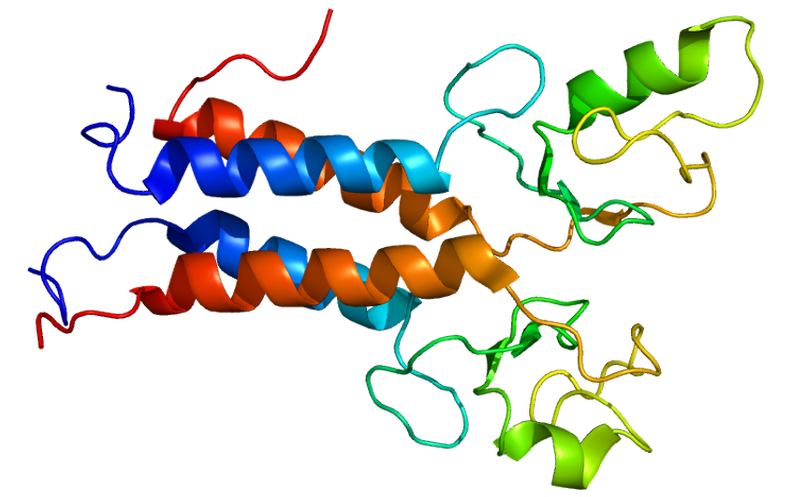

The gene produces a large ribbon-like protein, also called BRCA1. Protein repairs broken DNA, but only two pieces of ribbon, made up of several hundred nucleotides (the chemical "letters" A, T, C and G), really matter. Using a standard cell line, scientists therefore changed one letter at a time in these parts to one of three alternatives (eg, change an A to T, C or G), for a total of 3,893 variants, in cells of a beast of laboratory sum called HAP1. They called their approach, which used the CRISPR DNA editor to make these single letter changes, "saturation genome editing".

In each experiment, they simultaneously published a BRCA1 gene region in 20 million cells and allowed the cells to grow in laboratory dishes for 11 days. They then measured the effects of each letter change to see which ones killed the cells. This was an indication that the BRCA1 repair protein was impaired. In people, when this happens, damage to the DNA is not taken into account and the cancer can develop.

As a result, each of the 8993 variants of BRCA1 could be interpreted as affecting the BRCA1 protein and thus leaving a cell vulnerable to cancer or not.

About 72% of the single-letter variants had no deleterious effect on the BRCA1 protein; These do not cause breast or ovarian cancer, a result that matches the existing data. One-fifth of the single-letter variants were sufficiently harmful to the protein to impair its ability to repair DNA and thus increase the risk of cancer; this, too, agrees with the ClinVar data.

Shendure, Starita and their team are now using the same approach on BRCA2, a related gene whose variants may also cause breast and ovarian cancer.

Republished with permission of STAT. This article was published on September 12, 2018

Source link