[ad_1]

Martin Rees, a respected British cosmologist, made a rather bold statement about particle accelerators: there is a tiny but real possibility of disaster.

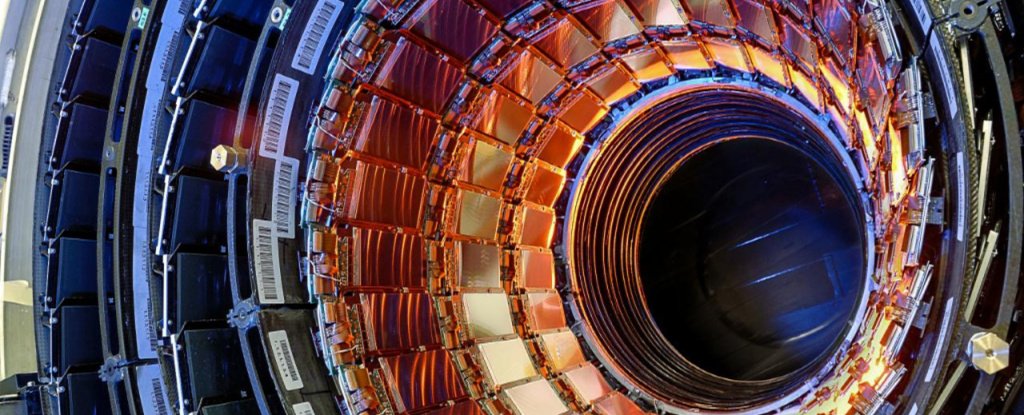

Particle accelerators, such as the large hadron collider, pull particles at incredibly high speeds, crush them and watch the fallout.

These high-speed collisions have allowed us to discover many new particles, but according to Rees, it's not without risks.

In a new book, called On the future: prospects for humankindit gives rather dark perspectives.

"Maybe a black hole could form, then suck everything that surrounds it," he writes, as Sarah Knapton reports to the Telegraph. "The second scary possibility is that quarks are grouped into compressed objects called strangelets."

"This in itself would be harmless, but under certain assumptions a strangelet could, by contagion, convert everything she encounters into a new form of matter, transforming the entire earth into a hyperdense sphere of about one hundred meters in diameter. "

It's about 330 feet, or the length of a football field.

And that's not all. According to Reese, the third way in which particle accelerators could destroy the Earth is a "catastrophe that engulfs space itself".

"Empty space – what physicists call emptiness – is more than just a nothingness.It is the arena of everything that happens.It contains all the forces and particles that govern the The current vacuum could be fragile and unstable. "

"Some have hypothesized that the concentrated energy created by the collision of particles could trigger a" phase transition "that would tear apart the fabric of space.This would be a cosmic calamity, and not only earthly."

It seems frankly terrifying. But should we really worry? Intelligent people in the LHC can certainly solve this problem.

"The LHC Safety Assessment Group (LSAG) reaffirms and extends the findings of the 2003 report that collisions at the LHC are safe and that there is no need for worry, "writes CERN on its website.

"Whatever the LHC does, nature has already done many times the life of Earth and other astronomical bodies."

And that's an important point: cosmic rays are natural versions of what the LHC and other particle accelerators do. And these rays strike the Earth constantly.

The team behind the LHC also has an answer for the strangelets.

"Could the strangelets merge with ordinary matter and transform it into strange matter?" This question was raised before the relativistic heavy ion collider, RHIC, was launched in 2000 in the United States, "they explain.

"A study done at the time showed that there was no reason to worry, and RHIC has been around for eight years, looking for strangelets without detecting any."

Even the late Stephen Hawking gave his blessing to the particle accelerator:

"The world will not end when the LHC starts, the LHC is absolutely safe, collisions that release more energy occur millions of times a day in the Earth's atmosphere, and nothing terrible happens. "said Hawking.

In a way, Rees is right. We are not 100% sure and may never be sure. But as he explains, many scientific advances can be risky, but that does not mean we have to stop completely.

"Innovation is often dangerous, but if we do not give up risks, we can give up benefits," he writes. In the future.

"Nevertheless, physicists should be cautious when carrying out experiments generating unprecedented conditions, even in the cosmos," writes Rees.

"Many of us are inclined to consider these risks as science fiction, but entrust issues that can not be ignored, even if they are highly unlikely."

We will leave this gigantic task to particle physicists.

Source link