[ad_1]

As you may have heard, NBC "Today" host Megyn Kelly's show was canceled this past week following her on-the-air remarks expressing acceptance of blackface. It's a racist show business practice But as "Sunday Morning" Contributor and WCBS Anchor Mauritius DuBois tells us, blackface has a long history in our country:

It happens all too frequently – often at Halloween, but not exclusively – as in 2016, when two white girls in Maplewood, N.J., posted a photo of themselves online in blackface. One student told a reporter, "They thought it was a joke, but it really was not funny at all."

One of the girls' mother said, "The two girls had no idea of what blackface was, or the history of it."

With the recent controversy over Megyn Kelley's remarks, Maurice DuBois looks at the long and complex history of minstrels and stereotyping in which white (and black) performers painted their faces black.

CBS News

The history of blackface is long and complex, and deeply ingrained in our culture – in vaudeville and minstrel shows and in movies. Even Bunny Bugs and Elmer Fudd blacked up.

For more than a hundred years, white (and then black) performers wore dark makeup, creating not only a popular theatrical form, but stereotypes that are still with us today.

Eric Lott, a professor at the Graduate Center of the University of New York City, admitted that blackface makes him uncomfortable. "It does make me feel uncomfortable to talk about these things because they are incredibly disturbing, and revolting," he told DuBois.

Lott says blackface represents a strange mix of envy, fascination, desire and fear.

DuBois asked, "Explain the fear part to me: What are these white performers, what are these white? [audiences], afraid of? "

"They are afraid of black groups, mobs rising up and taking power," Lott replied.

Minstrel shows began in the 1830s, and white performers used burnt cork, or later black greasepaint. Minstrelsy eventually became the most popular form of entertainment in the country.

Margo Jefferson, the Pulitzer Prize-winning critic, reviewed some images of minstrel shows from the New York Public Library. "The shininess of the black against the big white clown 's mouth, the hat, the over – long tailcoat … It' s always going to the jolt fun, that that rattles you still more. "

White minstrel performers claimed what they did on stage of their lives.

"Some of this is a fascination with the music, the songs, the performance styles of black people," Jefferson said.

But it's also where "Jim Crow Jump" was born, along with other characters depicted as lazy, lying or buffoonish – all happening before the Civil War. "Slavery was all about creating visions, types, stereotypes of an entire race of people as sub-human in every way," said Jefferson.

By the 1860s, African-Americans started using blackface onstage themselves.

DuBois asked, "Why on earth would a black performer put on blackface and demean him or herself?"

Jefferson replied, "Look, this is the 19th century, they had limited options.

Why? "Because it makes you feel comfortable, you can be fascinated, you can be excited, but you can always feel superior."

In effect, the black makeup on a black performer became a theatrical mask, with many layers of meaning. According to Professor Lott, "The mask, I think, says to white audiences, 'You have nothing to fear, Go ahead, enjoy yourself.' To black hearings I think any number of things might have been spoken, like, 'Can you believe that these people are making me on this mask so they will be entertained?' You know, in other words, there is a kind of winking to the black audience.

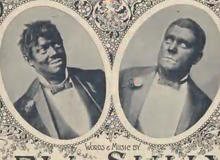

One of the greatest black stars to come out of the minstrel tradition was Bert Williams, who wore blackface from vaudeville to Broadway.

Black actor Bert Williams (far left) performs in blackface in the "Bert Williams Kiln Field Day Project Lime" (1913), believed to be the oldest surviving footage featuring black actors, recently discovered and restored by the Museum of Modern Art Film Archive.