[ad_1]

Image copyright

Alamy

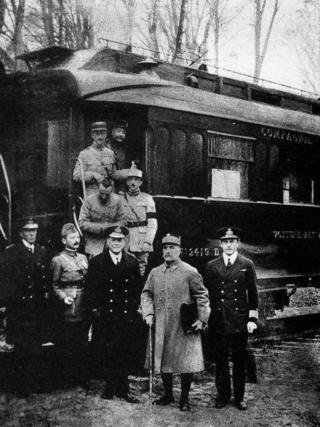

Rear Admiral Hope (front right) was part of the British delegation at the Armistice talks

After the years of bloody conflict, the Armistice was finally signed in November 1918. The arrival of American troops, earlier that year, saw the Germans grow progressively weaker and their officers privately conceded they had no hope of victory.

A series of letters, the most reliable form of communication in an age when electronic methods were in their infancy, marked the path towards peace.

The formal negotiations began on November 8, 1918 in a luxurious railway carriage in a forest near Paris.

The German delegation, led by Matthias Erzberger, had no choice but to accept tough terms demanded by Britain, France and America.

Sir George Hope, a member of the British delegation, wrote to his wife Arabella.

"Erzberger was very nervous at first and spoke with some difficulty, the general awfully sad, the diplomat very much on the alert, and the naval officer sullen and morose."

'Subordinate rank'

Rear Admiral Hope judged the accommodation "most comfortable".

"The British have a sleeper car with all possible conveniences: there are several other sleeping cars and a dining saloon," he wrote.

The German delegation was in a similar train, about 100 yards away.

They have hoped to make it "principally a civilian affair", notes Rear Admiral Hope.

"French and we are very angry with them for only sending military and naval officers of a rather subordinate rank."

The German party approached in a single file and got into the conference where "we received them stiffly but courteously".

The two sides exchanged salutes and lined up on the sides of the table, Rear Admiral Hope.

"The terms were then read out to them and obviously made them squirm, but they were probably prepared for the most part of the world."

Image copyright

Alamy

News of the Armistice is celebrated by Allied troops, among them the US 64th regiment

Rear Admiral Hope's private letter was first published in 1979 by Leeds University historian Peter Liddle, in his book Testimony of War.

"He was perfectly placed, superbly placed," Dr. Liddle told the BBC.

"It's not just a man's experience, in tiny, of events, it's a very important thing that was happening."

The Armistice 100 years on

Image copyright

AFP

Long read: The forgotten female soldier on the frontline

Video: War footage brought alive in color

Interactive: What would you have done between 1914 and 1918?

Living history: Why 'indecent' Armistice Day parties ended

It is one of five letters, written by Key players in the weeks before the Armistice, selected by Cambridge historian Sir Richard J. Evans and the Royal Mail, to highlight the crucial role of written communication and postal services in the Great War.

"Every fighting nation had a postal service," says Prof Evans.

"In Britain these were post office personnel who were given military ranks and a bit of training, but basically organized a worldwide postal service across the empire.

"And you had something similar to the Germans and the Austrians and so on, because it was very important to get letters to the troops and letters back, to maintain morale, and to have a very high level of communication."

The United States and the United States, leaving the German army unable to withstand a series of sustained attacks.

Image copyright

Alamy

Paul von Hintze said it was time to "give up the game" in Bulgaria

Germany became increasingly isolated, its allies dropped out of the war, among them, Bulgaria, where the government collapsed.

In a telegram on October 1, Germany's State Secretary for Foreign Affairs, Paul von Hintze, wrote to representatives at Army Grand Headquarters: "According to the most recent reports from Bulgaria, we must give up the game there.

"From a political point of view, there is no point in our relationship, let alone reinforcing them."

Image copyright

British Library

Within days, the Germans requested a truce.

Prince Max von Baden, Imperial Chancellor, wrote to the President Woodrow Wilson, offering to accept his terms.

Image copyright

US Archive

"In order to avoid further bloodshed the German government demands to bring about the immediate conclusion of a general armistice on land, on water, and in the air," he wrote.

According to Prof Evans, the German generals "thought they might be able to hold off the allies on the Western Front for a bit longer, but they were under no illusions about the fact that they were not going to win by this stage. thought it was best to sue for peace ".

He adds that the new democratic government is hoping that it will be fairly decent from the Americans, who were now calling the shots.

But on 27 October, Germany was further weakened, when Austro-Hungary left the war.

In a letter to Germany's Kaiser Wilhelm II, Austro-Hungarian Emperor Karl wrote: "It is my duty, but it is not enough, nor willing, to continue the war.

"I do not have the right to oppose this wish, since I have no hope for a favorable outcome.

"The moral and technical preconditions for it are lacking, and useless blood letting would be a crime that my conscience forbids me to commit."

President Wilson for harsher terms, says Prof Evans.

"They thought he was a bit wishy-washy, vague and idealistic, so they toughened up the terms of the Armistice."

The Germans said they would only negotiate with a democratic government, forcing the abdication of the Kaiser on 9 November.

Image copyright

Getty Images

US President Woodrow Wilson called the shots

The fifth letter shows how the Armistice was slow to spread distant parts of the war.

In east Africa, the British wanted to send a telegram to the German Colonel Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck, who had fought a successful guerrilla war against the British for four years.

'Under white flag'

But the British could not get him over to the Armistice when his troops captured a motorcycle despatch rider, carrying the telegram to be delivered "under white flag".

"The problem was … he could not believe the Kaiser had abdicated, and got in touch with the British High Commissioner for confirmation," says Prof Evans.

"Eventually it was given credible evidence that this was not a trick designed to trick the abandoning of the struggle and a formal termination of hostilities on November 25, 1918.

"So that's the last gasp of the war really … and it's the GPO (General Post Office) that plays a role in bringing it about."