[ad_1]

Australia is late for the space festival. The head of the new space agency, Megan Clark, said it herself. This continent, the ideal place in the southern hemisphere to scan the galaxy, was one of the last developed countries to have a space agency, and it did not understand why.

For example, last year, Clark led an expert panel to determine Australia's space capabilities, and what they found surprised them. The size of the existing industry was much larger than previous estimates. And never before has Clark seen such staunch stakeholders: the vast majority of players have long called for a space agency acting as a single Australian gateway to attract investment, support and advice.

"And that makes your job really easy, because then you can go to the government and say," The country is united, take a step here. There is no inconvenience; there is not one speaker who does not want it, "Ms. Clark said in an interview. "And it's not a small group, it's not a small voice, it's the nation that wants that."

The Australian Space Agency officially began operations a few months later, in July, with Ms. Clark's first Executive Director. She is now overseeing a plan to triple the value of the Australian space industry to reach between 7 and 9 billion dollars a year by 2030.

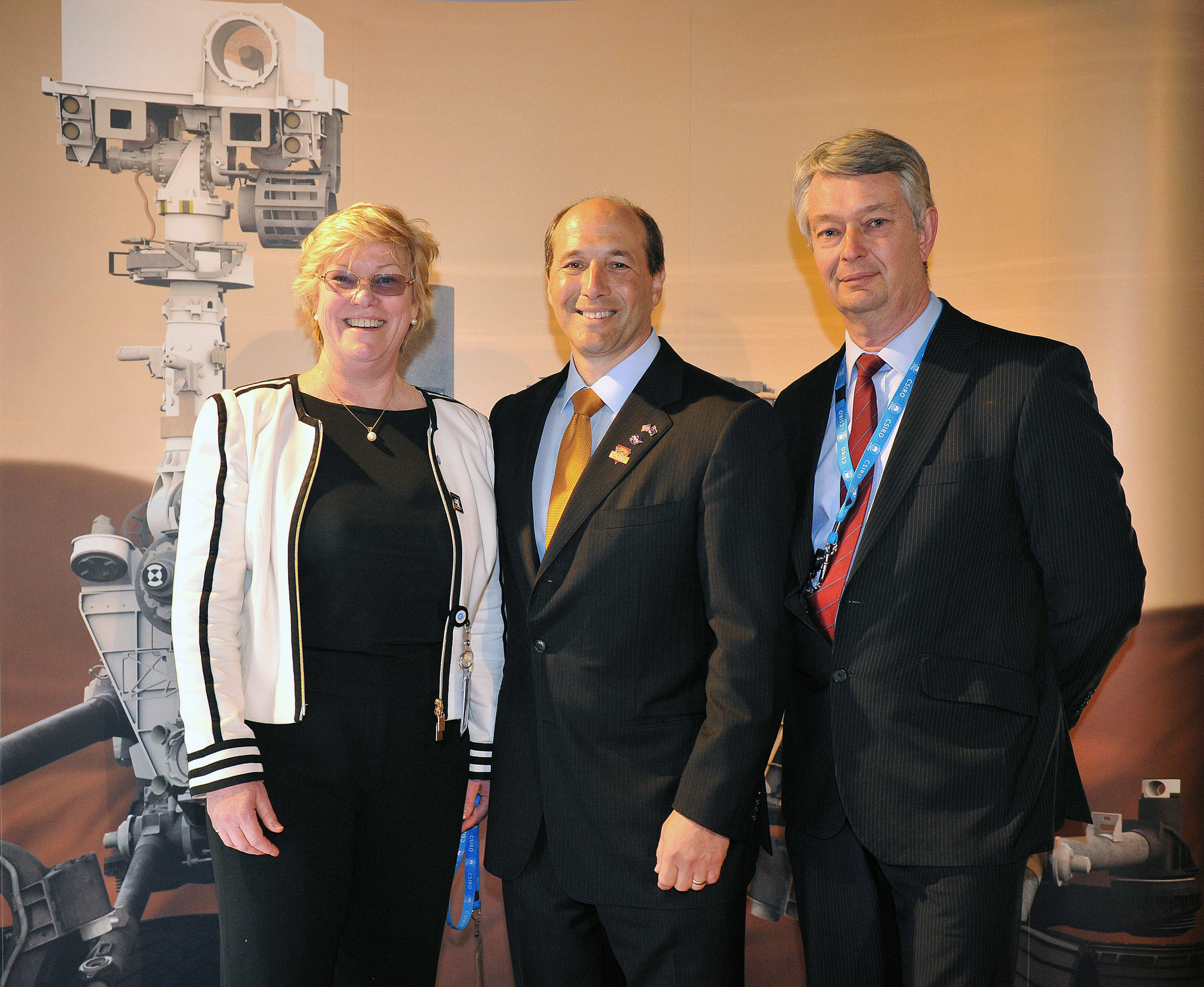

Ms. Clark and her team took the lead. The agency signed memoranda of understanding with French, British and Canadian space agencies, was hailed in a resolution passed in the US House of Representatives that promised increased cooperation and signed a declaration of intent with Airbus .

When the agency was announced, the public was a little skeptical about its tight budget of $ 30 million over four years. This led to cartoons of boomerang rockets and Internet jokes about a fake agency, Australian Research & Space Exploration, or ASS. (In comparison, NASA's budget this year is about $ 20 billion.)

Ms. Clark is not disturbed. For her, the size of the agency's budget is not a very important factor in her immediate success. While NASA's budget allows it to dictate the US space industry, the ASA's goal is to attract investment and create international partnerships, to guide the world's space industry, and to help it. Industry and federate under a national banner to help it grow – a much more difficult role to bear.

"The role of the government is shifting from donor to partner and facilitator," said Karen Andrews, Minister of Industry, Science and Technology, at the conference. 39, a speech at the Australian Conference on Space Research in September. "These partnerships should lead to new businesses, thus strengthening the growing dynamism of the industry."

Ms. Clark feels well equipped to guide the agency in her growth issues. Her career, which she calls "higgledy-piggledy", goes from mining geology to venture capital, through the banking sector, to become the first female director of CSIRO, an Australian scientific research agency. She explained that each of its functions was linked to the fact that the discovery had become an economic value – a major goal of most space agencies.

Like many of her colleagues, Clark has a childish wonder about the mysteries of space, especially the role of Australia in deciphering them. She spoke enthusiastically about the fact that the Curiosity rover had landed on Mars via the CSIRO-funded, NASA-funded Advanced Space Center near Canberra, Australia, while she was director of CSIRO. She marveled at a virtual reality program from a Melbourne-based developer, Opaque Space, which caught the attention of NASA and Boeing Defense.

Her mantra often repeated for herself is "do what you have in front of you". She has risen through the ranks of her career by tackling one task at a time, tactical of fighting the pressure that she has attributed to an experience lived at the age of 12 years. A doctor told her that if she did not overcome the debilitating nervousness that she was then enduring as a pre-teenager, she could never hold a stressful job in adulthood. In a sense, she dedicated her life to proving that this doctor was wrong.

She is not one to leave much of a problem with her quest for discovery being hindered by a discovery that caused her trouble in her early twenties: she was surprised while working in an underground mine in Western Australia, which was contrary to the rules.

"The game was then that if a mines inspector came, you would go to the surface, and as long as they did not see you working underground or until you worked" blatantly "underground, they would turn somehow a blind eye, "said Dr. Clark. "And I just thought it was lacking integrity:" That's what I do, and I'm not going to hide from that. "

At the time, his boss was ordered to fire or fire him, but he came to his defense and managed to obtain an exemption. The law had been amended shortly after, in 1986. It was a "confrontation", but she did not regret doing it. employment.

Clark grew up in Perth, the most isolated capital in the world and what she calls "the last capillary of the global network". She felt that there were only two career options in Western Australia promising a ticket to the world: mining and oil. She chose mining.

She has a strong sense of adventure, a trait that, she says, is typically Australian and has been gripped by the feeling that "the world is there, not here". She chose to do her Ph.D. in economic geology – Queen's University in Ontario, Canada – looking for where you would end up if you pinned a pin around the world from Perth.

Now, she says, the next generation of Australians should exploit this adventurous instinct to travel beyond the planet, not just on the other side of the world. The opportunities for Australians to enter the space market are obviously slim – the three Australian astronauts have been granted US citizenship and have gone to work for NASA – but she now wants to recover the lost potential.

Her busy schedule makes her forget, sometimes, how much her presence at the head of the space agency and as a woman can be influential. But she has received a flood of letters from young boys and girls reminding her of the power that space should inspire young people.

"You see that in space, that curiosity you had when you were a child, some people get beaten up, but others do not, and they end up in the space sector," he said. she said. "This curiosity is really important, and that feeling of being a kid and being a bit nerdy about it."

Australia might not launch its own rocket on Mars any time soon. But she is confident to see a human being on the red planet during her life and she hopes that an Australian will be part of it.

Source link