[ad_1]

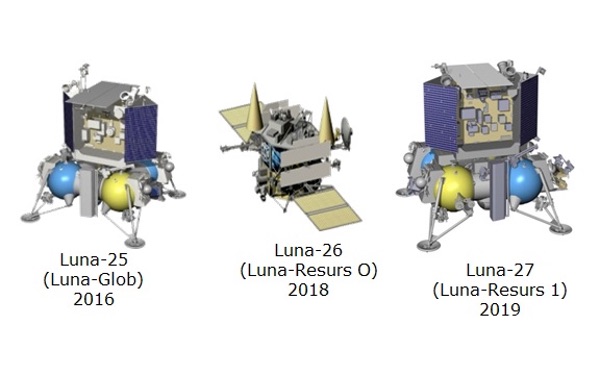

Russia has planned a series of lunar missions, but their calendars have suffered significant delays. (credit: Institute of Space Research of the Russian Academy of Sciences) |

by Dwayne A. Day

Monday, November 26, 2018

![]()

In a little less than two weeks, China will launch Chang'e-4 on the Moon in order to do what no other country has done yet: land at the far side of the moon, a currently planned for early January. China is planning follow up missions to the moon, each with new engineering goals and new scientific discoveries.

| The once proud Russian space program did not lack ideas or even money. However, he lacked any kind of organization or direction, as well as the experienced manpower, needed to accomplish something beyond the low Earth orbit. |

But just a few years ago, Russian scientists had presented an impressive set of lunar exploration plans, including lunar poles, drilling instruments and even a sample of spacecraft. These plans have been steadily reduced and launch dates have declined, and Russia's ambitions for independent planetary exploration have virtually disappeared. While many other countries are looking to send spacecraft to the moon and Mars, Russia's space program is intended for the planets only if someone else agrees to pay for most of them. the bill.

Almost 30 years have now passed since the last Russian planetary mission, even partially successful. After sending many spacecraft to the Moon, Mars and Venus, Soviet planetary exploration collapsed with the Soviet Union. The once proud Russian space program did not lack ideas or even money. However, he lacked any kind of organization or direction, as well as the experienced manpower, needed to accomplish something beyond the low Earth orbit.

During the 1990s, many Russian space scientists remained unpaid and have no new mission to work on. The lucky ones have moved to the West, some have found jobs in European scientific institutions and some have even found themselves in the United States. Many others simply left their fields entirely. By the turn of the century, there were only a few experienced space scientists left in the country.

The few scientists who remained were still talking about future projects that were less impressive than delirious. In 2010, a presentation of the Lavochkine Association indicated up to 33 Russian planetary missions planned between 2012 and 2020, a rate of about four per year, well above that of NASA, which represents on average a Handful of planetary missions by decade. The real number achieved by Russia during this period is zero. In 2011, Russian scientific presentations showed many planned missions on the Moon, Mars, Mercury and Venus, none of which were built. (See "Red Planet Blues," The Space Review, November 28, 2011.)

These noble Russian projects were highlighted at the end of the year 2011. In November of the same year, Russia launched an impressively technical mission on the Martian moon Phobos, which did not never even escaped Earth's orbit. The Fobos-Grunt Space Shuttle was supposed to travel to Mars, land on one of Mars' two moons, recover from the Earth and bring it back to Earth. If it had worked, it would have been an incredible feat and unequaled in planetary science. But it was too ambitious given the Russian experience over the previous quarter century. The previous Russian planetary scientific mission, known as Mars 96, had not even reached Earth's orbit and could have sank into an Andean mountain flank. Prior to that, the Fobos 2 mission had entered the orbit of Mars in January 1989, but had failed shortly thereafter.

The failure of Fobos-Grunt put the Russian planetary program in search of other objectives and their attention turned to the Moon. At the beginning of this decade, Russian scientists published documents showing a series of half a dozen more and more sophisticated robotic lunar missions, including deep drilling, polar ice analysis, and sample returns. In 2013, two years after the failure of Fobos-Grunt, the Russian Space Agency announced that its next global science mission would be launched in 2015 and would orbit the Moon, followed by a lander a year later ( see "A Russian Moon?" Space Review, January 28, 2013.)

| There was no reason to believe that government leaders would endorse unimpressive space science missions, which would not be comparable to what other countries were doing. |

No mission has yet been launched and every new announcement about them seems to push them further in the future. The lander, formerly Luna-Glob but renamed Luna 25 to emphasize the continuity of the series of Soviet Luna missions that ended in 1976, was to be launched in 2016, then 2019, but it is apparently planned in 2021, the orbiter is now late. until 2022. Although Russian television published several years ago images of what was apparently engineering test equipment for a Russian lunar lander, it is difficult to know when, or even if, the Russian lunar plans progress despite official declarations.

Russia has been describing for several years a series of increasingly ambitious robotic lunar missions, such as this painting of a 2014 presentation. But we do not know when or even if the first of these missions will fly. (credit: ESA) |

From the early 2000s until at least a few years ago, the Russian planetary science program seemed to have come up with an enigma: national pride – and perhaps the only way to get funding of the government – meant that they would only propose bold and ambitious space missions that did what no country had done before, but such missions also exceeded their engineering capacity. .

Realistically, the Russian space program needed a series of less ambitious but achievable missions that would allow the country to rebuild its technical and scientific capabilities by training a younger generation – learning again how to crawl before they can walk . But there was no reason to believe that government leaders would endorse unimaginative space science missions, which would not be comparable to what other countries were doing. With American rovers on Mars and spacecraft in orbit around Mercury, Mars, Saturn and Jupiter, and flying over Pluto; with China landing a mobile on the moon; and even with India orbiting Mars, any Russian planetary space mission not doing something with a substantial advertising benefit seemed to be a non-starter. Now, Japan is building a Phobos back sample spacecraft aiming to accomplish in the 2020s what Fobos-Grunt was supposed to do.

Fortunately for the Russians, the Europeans knocked on their door. This decision results from the cancellation by the United States of a joint agreement between NASA and the European Space Agency on the exploration of Mars in 2011. Although the internal deliberations of the government Russian on the subject are unknown, senior officials were apparently more willing to approve cooperation projects with Europeans. on Mars than to fund a Russian lunar exploration effort. Russia is currently developing a lander for the European ExoMars rover, whose goal is to launch in 2020. According to information, 80% of the lander will be built by the Russian company Lavochkin and the 20% remaining, namely guidance, radar and navigation systems. – will be built by ESA, although the exact calculation of the 80/20 distribution is unclear. If ExoMars works, the Russians will be back in the global science, but even if Russia pays substantial funds to the mission, it is clear that the Europeans are setting goals.

| If the manned space flight program suffers, there is no reason to think that even the nascent Russian space flight is immune. Europeans who use the Russian Mars material are almost certainly worried about their partners. |

At the very moment when Russian lunar projects collapsed, the Chinese were on the rise. China's successful Chang'e-3 mission that set a lander and Yutu rover on the lunar surface will be followed by the Chang'e-4 lander and the rover on the far side of the moon. China has also announced its intention to carry out a mission of return of samples of proximity and perhaps even a mission of return of samples of the South-Pole-Aitken basin which would make it possible to reach a priority American scientific objective for the Moon . This Chinese lunar exploration program is more ambitious than the Russian plans abandoned only a few years ago and more ambitious than the current NASA robot lunar plans. (A few weeks ago, a US official unveiled details of an agreement reached in 2013 with China on the agreement regarding the landing of Chang-e-3, the United States has confirmed its part of the agreement, but China did not do it.) ambitious "Mars 2020" mission including an orbiter, a lander and a rover. India currently has a spacecraft in orbit around Mars for a long time, and is working on more ambitious missions.

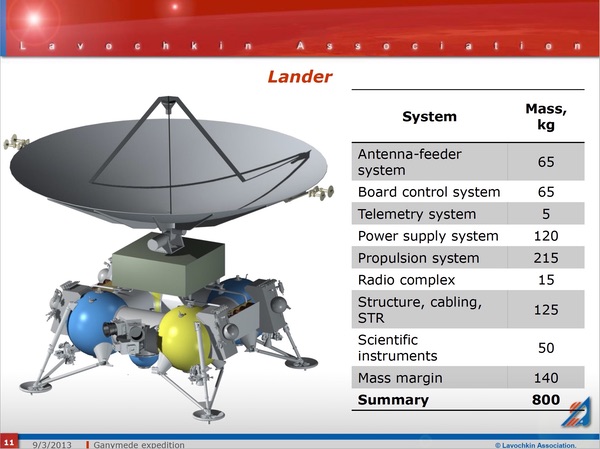

Illustration of a 2013 presentation of the Lavochkin Association on a proposed lander for Ganymede. Many Russian proposals for an advanced planetary spacecraft have been proposed over the last decade, but the country is not able to carry out the most basic missions, while India is currently in orbit around Mars and that China is landing on the moon. (credit: Lavochkin Association) |

The recent abandonment of the launch of Soyuz shows how much the Russian space program has fallen. Spaceflights have never been easy, but while other parts of Russia's space infrastructure had failed, human spaceflight seemed at least protected. Not anymore. And if the human space flight program suffers, there is no reason to think that the Russian space flight, even nascent, is immune. Europeans who use the Russian Mars material are almost certainly worried about their partners.

Today's landing on InSight Mars kicks off the United States, China and Japan over five exciting weeks of global science. OSIRIS-REx arrives on the asteroid Bennu next week, followed by the takeoff of Chang'e 4. At the beginning of the year, Ultima Thule will be flown over by New Horizons, the Japanese shuttle Hyabusa2 will rise from her temporary sleep and will resume the investigation on its asteroid 162173 Ryugu, then Chang'e 4 will land on the opposite side to the Moon.

In a recent article, Russian space expert Jim Oberg highlighted the internal management problems that contributed to the failures of the Russian mission. He mentioned a poem by Sergey Zhukov, cosmonaut trainee, space flight lawyer and senior official. Zhukov wrote several years ago a poem entitled "Epitaph for the Russian Space Agency (1992-2015)", troubled by the disrepair of their space program. "The translation of Zhukov's poem by Oberg perfectly describes the Russian space exploration program:

Students sank to the west

Doctors – who is in China, who in Iran?

Only the yellow tape of the film

Preserved the prestige of the Russians.

Erect a pile of paper,

Our administration has become sickly and shallow …

And he stands in tears

At the threshold of the universe, the poet.

He looks through open eyes

In the deep space, and there are no Russians there …

Note: We are temporarily moderating all under-committed comments to cope with an increase in spam.

<! –

->

Source link