[ad_1]

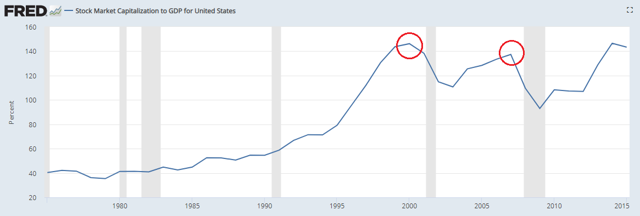

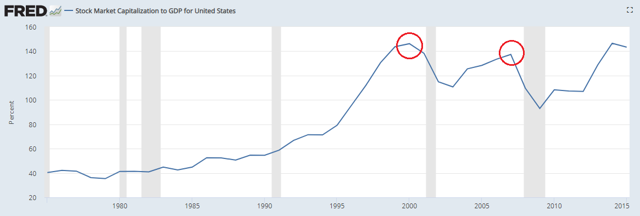

I've recently started finding articles indicating that one of Warren Buffett's favorite valuation indicators, namely the US's total market capitalization and US GDP, shows that the stock market is in or out. close to a bubble. Looking at the graph of total market capitalization relative to GDP presented below, we do find that we are approaching the previous peaks (circled in red) observed during the technology bubble and the real estate bubble.

The problem is that total market capitalization relative to GDP is an imperfect means of determining whether or not we are in a market bubble. There are three main problems with the use of this indicator which I will discuss below.

Problem 1

The main problem of the relationship between total capitalization and GDP probably lies in the fact that we only compare companies that make money at home and abroad only with US GDP. In 2017, approximately 44% of S & P 500 company revenues came from abroad (yes, the ratio uses the entire stock market, but the S & P 500 accounts for about 80%, making it a good proxy). Why do we compare the capitalization of the US stock market only to US GDP? This ratio may vary from year to year depending on exchange rates, corporate headquarters, and how market indices determine what matters to a domestic company or international business. There is no reason to expect a market index with a large international component to have a stable relationship with US GDP.

Problem 2

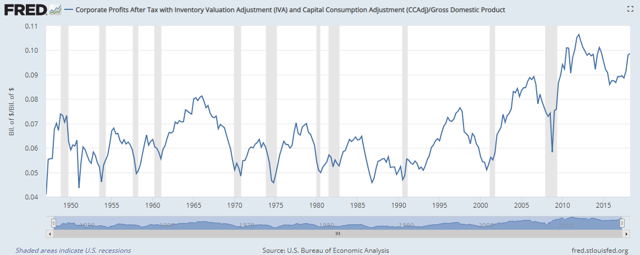

The second problem related to the use of total market capitalization in relation to GDP is that it ignores the distribution of profits in the economy. If larger firms realize higher profits and get a larger share of GDP, it makes sense that the value of the stock market is greater than that of GDP. The chart below shows the after-tax profit margins of corporations since 1947.

After-tax corporate profits revolve around all peaks. As long as higher valuations (ie higher total market capitalization) are supported by higher profits, it is difficult to show that we are in a bubble. I've read arguments that, if profit margins returned to the average, then the market is overvalued, but I have not yet heard the compelling arguments about why profit margins should. Maybe they will, but then corporate profit margins, not total market capitalization relative to GDP, would be your preferred measure of valuation.

Problem 3

The third and final major issue facing this evaluation measure is the fact that it ignores the public composition in relation to the private composition of US firms. The measure uses the total market capitalization of all publicly traded stocks. If the proportion of corporate profits earned by SOEs and the proportion of profits made by private firms change over time, this measure of valuation will also fluctuate.

Indeed, it is exactly what we have seen happen. Although the number of public enterprises has increased from around 6,000 during the technological boom to just over 3,000, the proportion of profits made by public enterprises is still quite high. In 1957, the S & P 500 was valued at $ 172 billion and was trading at a P / E of around 13.3. Using FRED's after-tax corporate profit-sharing quarterly data, we find that this equates to public enterprises earning about half of all corporate profits. In 2017, the S & P 500 was valued at $ 23.9 T and the P / E at 21.4, generating implied profits of about $ 1.12 T in total. The annual corporate earnings rate for the economy as a whole was about $ 1.82 billion, so the S & P 500 accounted for about 62% of all corporate profits.

We used data for the S & P 500 rather than for the entire market because it was much easier to access. It should also be noted that the earnings of S & P 500 obviously include the profits from international operations (as we pointed out in our first point). Therefore, the use of data for the entire market or the adjustment of other factors could give slightly different percentages, but that is the point. The percentage of business profits that the market represents changes over time, whether because of the mix of public companies and private companies or the effect of international profits.

summary

These are just three of the major problems associated with using total market capitalization to US GDP to determine whether the stock market is cheap or not. All of the changing variables that make up the measure mean that it is impossible to find an average or median of long-term fair value or any other method to determine whether the ratio is too high (bubble) or too low (excellent opportunity purchase). ). This does not mean that you can not pretend that the market is a bubble or that the market will not go down. It simply means that using this particular metric to make this point makes no sense.

Disclosure: I / we have no position in the actions mentioned and we do not plan to enter positions in the next 72 hours.

I have written this article myself and it expresses my own opinions. I do not receive compensation for this (other than Seeking Alpha). I have no business relationship with a company whose stock is mentioned in this article.

[ad_2]

Source link