[ad_1]

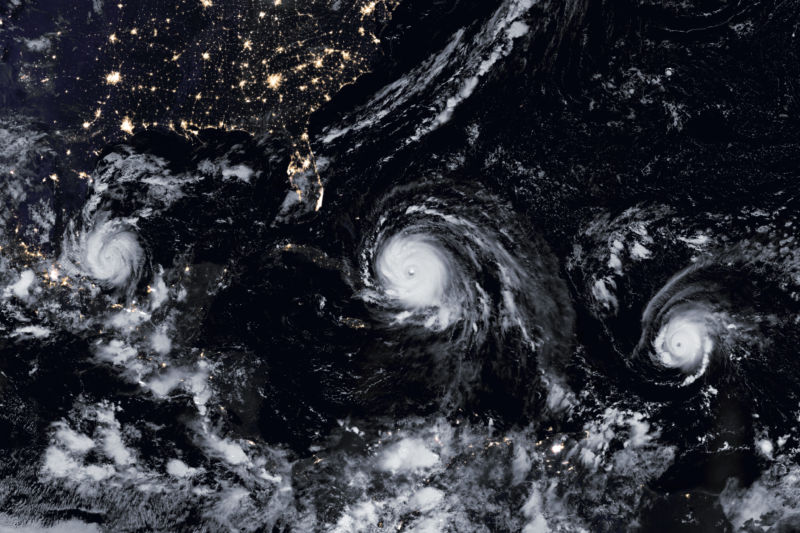

Many people would prefer to forget the 2017 hurricane season in the Atlantic, and many are no longer alive because of it. Hurricanes Harvey, Irma and Maria were all destructive when they landed, and three other major hurricanes (category 3 or more) have happily created their lives over the ocean. In an average year, the Atlantic has 2.7 major hurricanes, six of which are very unusual.

The birth and life of tropical cyclones in a fluid and agitated atmosphere are incredibly complex. But looking back, we've learned that some ocean models tend to stimulate or slow down the hurricane season. To study the factors responsible for the 2017 hurricane season, a team led by NOAA's Hiroyuki Murakami drew on this knowledge, as well as on climate model experiments.

Forecast models

Hurricanes in the North Atlantic are born just above the equator as a low pressure center. As this low pressure moves westward with the prevailing trade winds, it can continue to organize in powerful cyclone if the sea surface is warm and if the winds at altitude are mild enough to allow the storm to climb.

The sea surface temperatures in the region where hurricanes are born are obviously important, and some oscillations in the Atlantic Ocean can push these temperatures above or below normal. These higher winds may also be above or below normal strength for several reasons. Sea surface temperatures along the east coast of the United States appear to be having an effect, with warmer temperatures resulting in stronger winds. El Niño / La Niña oceanic temperature shifts from one year to another in the Pacific also play an important role, with stronger strong winds preventing the development of hurricanes in the El Niño years.

To test these different factors individually, the researchers used the same high resolution NOAA model that produces a forecast of hurricane activity at the beginning of the season. In a series of experiments, researchers have modified temperatures in one region or another to observe the effects on simulated hurricanes during the rest of the year.

If the global sea surface temperature is set at an average of 1982 to 2012, the model simulates three major hurricanes, unsurprisingly. Starting from the actual temperature model of early July 2017, the model correctly simulates about six major hurricanes instead.

What is the key?

Taking 2017 temperatures and replacing one region at a time shows interesting results. Replacing the La Niña model in the Pacific – which usually boosts hurricane activity – with an El Niño has only had a minor impact. On the other hand, the suppression of warm Atlantic temperatures with the longer-term average has reduced the number of major cyclones from six to about four. So it seems that the Atlantic has more responsibilities than the Pacific, in this case.

The researchers also tried to replace only the area along the east coast of the United States, which may affect the upper winds, but this did not reduce the number of major cyclones. The replacement of the Atlantic tropical zone, where these hurricanes were born, however, took place. It reduces it even more.

Finally, the researchers examined the effects of global warming. Using medium and high greenhouse gas emission scenarios, they added our higher than expected ocean temperatures for 2017 or the longer term average. In both cases, the model simulated even more major hurricanes. When the 2017 temperature structure was used as a base, its six major hurricanes reached eight or nine.

In the end, the conclusions of the study are a little delicate. The most important factor of the hurricane season in the Atlantic in 2017 seems to have been the rise in ocean temperatures in the tropical region where hurricanes form first. The reason the water was particularly hot is when things get cloudy. The multiple back and forth of natural variability in the Atlantic have probably contributed. But it may be that human-induced warming has also contributed – this study can not attribute blame to it.

Climatologists have a number of general expectations (usually bad news) for future tropical cyclones around the world, but very specific issues (as if we were going to see the hurricane season more often in the Atlantic ) are more blurred. Several moving parts must be pinned before you can see their net effect.

The continental United States have had a series of victories without a major hurricane between 2006 and 2016, a series that broke down sharply in 2017. The analysis following the 2017 hurricane season allows researchers to better understand these deadly storms and better understand how they will respond to our ongoing global warming.

Science, 2018. DOI: 10.1126 / science.aat6711 (About DOIs).

Source link