[ad_1]

Kristen Philman first tried methamphetamine in her early twenties, as an alternative to heroin and other opioids. When she discovered that she was pregnant, she said that it was an alarm bell and that she did what she had to do to stop consuming all of these drug addicts.

Theo Stroomer for NPR

hide the legend

activate the legend

Theo Stroomer for NPR

Kristen Philman had already been taking heroin and prescription pain medications for several years when one day in 2014, a family member offered her methamphetamine, a chemical cousin of amphetamine, a stimulant.

"I did not have a heroine at the time," says Philman, a resident of Littleton, Colorado. "I thought to myself:" Oh, that could reassure me. " "

That's the case, she says. Soon she was regularly using heroin and methamphetamine.

"With heroin, I began to fall asleep and needed methamphetamine to give me a boost," she says. "It was a daily affair, I would do heroin and methamphetamine on top of that."

Then, in December 2017, after a few months of no menstrual bleeding, Philman had a home pregnancy test and the result was positive. "I was really scared, because I had used methamphetamine and heroin of the day [my son] was designed until the day I took the [pregnancy] test, "she says.

Philman is among thousands of women in the United States who used the Stimulants of methamphetamine or amphetamines prescribed during pregnancy in recent years, researchers said Although this trend attracts little media attention, doctors in some areas are struggling to tackle the problem and the impact of this drug on women and infants.

Philman went into convalescence once she was pregnant and was given methadone for her use of opiates. She says her OB-GYN was sincere with her about the potential effects of her use of methamphetamine on the fetus – including premature birth and death.

Theo Stroomer for NPR

hide the legend

activate the legend

Theo Stroomer for NPR

Philman went into convalescence once she was pregnant and was given methadone for her use of opiates. She says her OB-GYN was sincere with her about the potential effects of her use of methamphetamine on the fetus – including premature birth and death.

Theo Stroomer for NPR

Since there are no drugs to treat the disorder related to the use of methamphetamine, some providers had to improve their treatment methods, while others were still unaware of the problem and how to treat it. treat.

A study published Thursday in the American Journal of Public Health confirms the increase in methamphetamine use among pregnant women and provides new data illustrating the magnitude of the problem. The research, which analyzed hospital discharge records between 2004 and 2015, revealed that the use of opioids in pregnant women has increased in recent years, as has their use of amphetamines and in particular methamphetamine.

Although this class of medications includes prescription medications such as Adderall and Dexedrine, which are sometimes used to treat Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder, we believe that our results represent almost entirely illicit methamphetamine use at the University of Michigan and the main author of the study.

The increase in amphetamine use began after 2008-2009, according to the study. In 2015, however, tens of thousands of pregnant women were taking these drugs.

"In total, we identified 82,000 deliveries affected by amphetamine-related disorders," Admon said.

According to the study, the increase in amphetamine use rates has increased disproportionately in three regions of the United States – the South, the Midwest and the West. Rural areas had higher rates than cities, with the rural West posting the highest rate of any region. Opioid use among pregnant women, on the other hand, was highest – 3% of all hospitalizations for delivery – in rural areas of the northeastern United States.

"In 2014-2015, a disorder of amphetamine use was identified among about 1% of deliveries in rural areas of the United States from the West," said Admon. And it's higher than the prevalence of opioid use among pregnant women in most parts of the country.

Effects on the health of mother and baby

Long-term use of methamphetamine during pregnancy has serious health risks for the mother, says Admon. It increases the risk of dying during or after childbirth or having life-long health complications – "things like blood transfusion, heart failure, cardiac arrest," she says. . "And then, eclampsia – which is the most serious form of preeclampsia – where a woman has a seizure."

"It's something we see here," says Dr. Tricia E. Wright, OB-GYN and Associate Professor at the John A. Burns School of Medicine at the University of Hawaii. Wright treats pregnant women who have been using methamphetamine for many years.

The increased risk of preeclampsia indicates an increased risk of heart attacks and strokes for the mother later in life, she adds.

If the mother continues to use the drug during pregnancy and does not receive prenatal care at an early stage, the consequences can sometimes be fatal.

"I have recently had a maternal death due to the use of methamphetamine," Wright said.

The woman was 28 weeks pregnant, "had a very serious heart condition" and did not receive any prenatal care, Wright says.

"She had a heart attack at home while using drugs," says Wright. The woman 's boyfriend gave her chest compressions and took her urgently to the emergency room, where the doctors performed an emergency caesarean section and gave her given vital support. But neither the mother nor the baby survived.

The new study found that methamphetamine and Prescription amphetamines also pose some risks to the infant.

This increases the risk of premature birth. It also increases the risk of developing a condition called placental abruption, which cuts oxygen delivery to the fetus and causes heavy bleeding in the mother.

The new study is important, says Wright. "This shows that by focusing on opioids in this country, we can not forget other drugs, especially methamphetamine."

In the late 2000s, national attention tended to turn away from methamphetamine because the use of methamphetamine was supposed to decrease, said Dr. Mishka Terplan, OB-GYN and addiction specialist at Virginia Commonwealth University. But health care providers working in rural areas in some parts of the country have never really seen the drugs disappear, he says.

"And many have noticed an increase in the use of amphetamine and methamphetamine in general, as well as in pregnant women," Terplan adds.

Challenges of treating the use of amphetamine during pregnancy

"More than half of our patients treated for opioid use disorders also have stimulant consumption disorders, which means they regularly take methamphetamine," said Dr. Amanda. Risser, family physician at Oregon Health & Science University in Portland. who runs a program called Project Nurture for pregnant women with substance use disorders.

Amanda Risser runs a program at Oregon Health & Science University in Portland, Oregon, aimed at pregnant women with substance abuse issues. At present, there is no medication available to treat methamphetamine addiction, and residential treatment is often the best option for patients.

Beth Nakamura for NPR

hide the legend

activate the legend

Beth Nakamura for NPR

Amanda Risser runs a program at Oregon Health & Science University in Portland, Oregon, aimed at pregnant women with substance abuse issues. At present, there is no medication available to treat methamphetamine addiction, and residential treatment is often the best option for patients.

Beth Nakamura for NPR

"Since we started doing this job in 2014, we have always taken care of women who tend to use methamphetamine along with the opiates they consume," Risser said.

Her colleagues from clinics in rural Oregon have observed the same trend there, she said.

Most patients want to stop taking medication during pregnancy, says Risser, but it's hard to stop amphetamines.

The minimum observed with the weaning of methamphetamine is strong, she says. Women feel depressed, unhappy and uncomfortable. This is because the long-term use of meth "may result in a significant decrease in neurotransmitters responsible for the well-being and happiness of people."

And unlike opioids, there is no medication to help patients with methamphetamine withdrawal. Thus, despite their best intentions, some Risser patients continue to use methamphetamines even as they begin their methadone treatment for opioid use.

The best treatment option for these patients is "time and support," says Risser. His clinic also offers behavioral therapy to help patients not to use methamphetamine.

The project also provides for residential treatment, which allows women, many of whom are homeless, to get off the streets and be safe during their pregnancy – as well as after the birth of their child.

"Access to high quality residential treatment is very important," Wright says.

Having a favorable OB-GYN made all the difference for Philman's pregnancy. When she learned that she was pregnant, she rushed to the Denver Recovery Group, where she was treated with methadone for her use of opiates. She found an OB-GYN who supported and understood her drug use, says Philman, while being frank with her about the potential effects of methamphetamine use on the baby.

"I was afraid my son had a physical problem," recalls Philman.

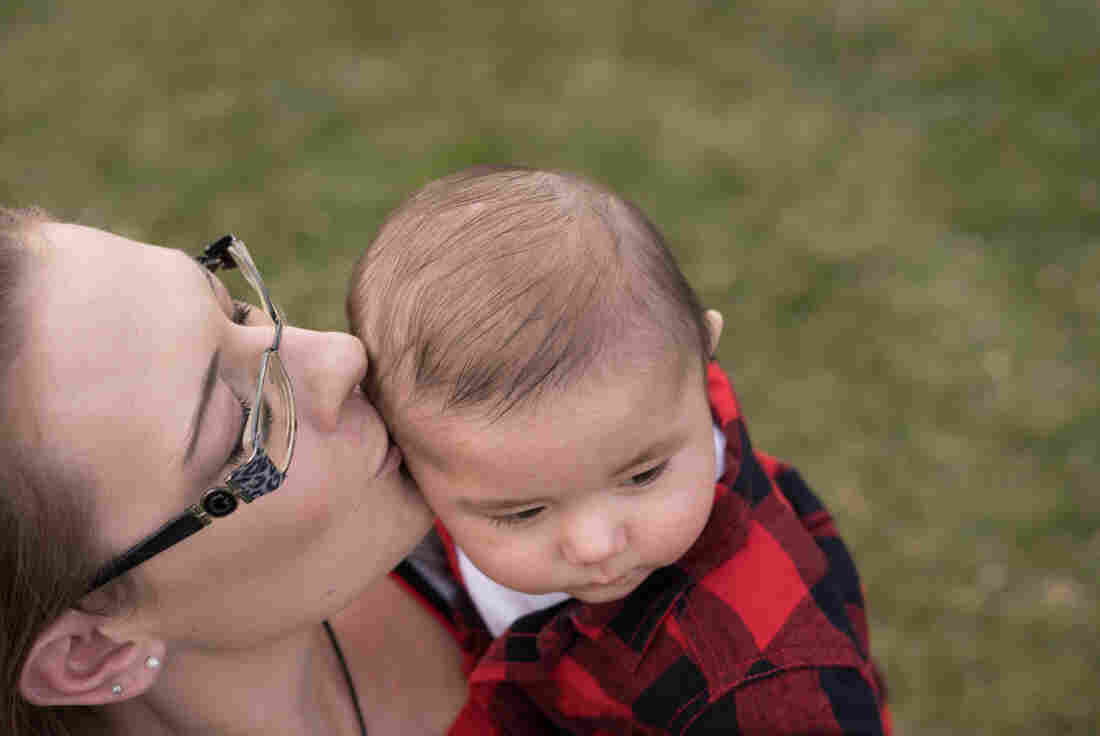

Philman holds his six-month-old son, born in good health.

Theo Stroomer for NPR

hide the legend

activate the legend

Theo Stroomer for NPR

Philman holds his six-month-old son, born in good health.

Theo Stroomer for NPR

This fear and concern for her son's health, and the support of her doctor, her parents, and her Denver Recovery Group advisor helped her through methamphetamine withdrawal, she says. What also helped, she says, is that her partner also stopped using drugs and was about to recover.

Still, the first month of treatment during her pregnancy was difficult, she says, and she returned briefly to methamphetamine two to three times. But after that, she stayed clean.

Monthly ultrasounds have been a big motivation, she says. "To see my son growing up was a kind of confrontation with reality."

Persistent stigma of addiction

Still, many pregnant women are not as lucky as Philman to find doctors or nurses supportive.

When Andrea Rano, a resident of Portland, became pregnant in 2016, she was living in a friend 's garage with her boyfriend of the time. Both used opioids and methamphetamine. In the following months, Rano worried about her pregnancy and felt guilty and ashamed of her addiction. These feelings only fuel her drug use, she says, and prevent her from seeking care.

When she went to the hospital to receive a dose of methadone, the nurse practitioner she met was discouraging and insisted on doing a urine test for the drugs, says Rano. and threatened to report it to the authorities.

"I ended up leaving this hospital and I felt really uncomfortable with the doctors and the health care after that," she says, starting to cry. "It was really hard to be in this situation – wanting to get help and having the impression that it was impossible."

She felt frightened, ashamed and helpless. "All I could think of was, what am I going to do, how am I going to help, is there any help for me, and even if I get help, will it matter? Because they kidnap my child anyway? "

This is the situation in which many pregnant women like Rano are found, says Dr. Curtis Lowery, chairman of the OB-GYN department of the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, in Little Rock. (Arkansas). Most doctors share the societal prejudices about drugs. Lowery adds that physical education does not address substance abuse issues or how to deal with these issues.

"This is not something that most OB-GYN residencies or family medicine training exposes to their residents," Lowery said.

But this stigma can endanger the lives of these women and their babies.

"The worst thing we can do for pregnant women is to defame them as a result of any type of drug use," Lowery said. "All you're going to do is drive them underground."

What they really need is good prenatal care and help to avoid medications, he says. "One of the things you do not want to do with methamphetamine addiction is the delayed treatment," says Lowery. "The sooner the patient is released from the drug, the better for the fetus and the mother."

And that's the good news: with proper help, women can recover from their addiction to drugs and then have a normal pregnancy.

"We know that screening, early management and stopping treatment at any time during pregnancy – give better results and normal results," Wright said. And "the longer they can stay sober, the more chance they have to recover."

Philman has not used methamphetamine or opioids for nearly a year. She returns there to finish her studies – she is enrolled in university courses that will begin in January.

Theo Stroomer for NPR

hide the legend

activate the legend

Theo Stroomer for NPR

Philman has not used methamphetamine or opioids for nearly a year. She returns there to finish her studies – she is enrolled in university courses that will begin in January.

Theo Stroomer for NPR

It was the happy experience of Philman and his son, full-term and 6 months old in good health. His mother has been out of drugs for almost a year and is already registered to return to university in January.

Although Rano was not so lucky at first, someone finally told him about the Nurture project in the seventh month of her pregnancy.

At the time, she lived in a car with her boyfriend and their dog. He was still taking drugs. Rano was taking methadone for his use of opioids, but was struggling to stay out of methamphetamine.

With the support she finally got from Risser, with a residential treatment at Project Nurture and the support of her counselor, doula and other women treated in the program, Rano was able to turn a corner.

She was able to avoid methamphetamine for the rest of her pregnancy. His son was born three weeks ago – but he was and still is in good health.

"It was the most amazing thing of all time," says Rano. "He was so handsome, I was so happy to have been there and done that – and that he was there and that he was fine."

She credits her recovery and the health of her son to Project Nurture. "I have a huge support network [there], "she says." I had a doctor who was absolutely amazing. I had a hospital treatment, which consisted of having a place to live, a place to bring my child home after delivery. It totally changed my life. "

[ad_2]

Source link