[ad_1]

Photographer: Jonne Roriz / Bloomberg

Photographer: Jonne Roriz / Bloomberg

Global gaps in access to Covid-19 vaccines raise concerns that the continued spread of the coronavirus will produce more dangerous versions of the pathogen, weakening medical weapons and further crippling economies.

In a race to catch up with emerging coronavirus variants, rich countries are already benefiting from powerful vaccines. While the United States, Great Britain and the European Union have given citizens 24 million doses to date – more than half of the injections administered globally – many countries have yet to start their campaigns.

Disparities in immunity pose a threat to states that have wealth and those that do not. Giving the coronavirus the opportunity to move forward and generate new mutants would have significant economic and public health consequences, adding to the pain, with the death toll surpassing 2 million.

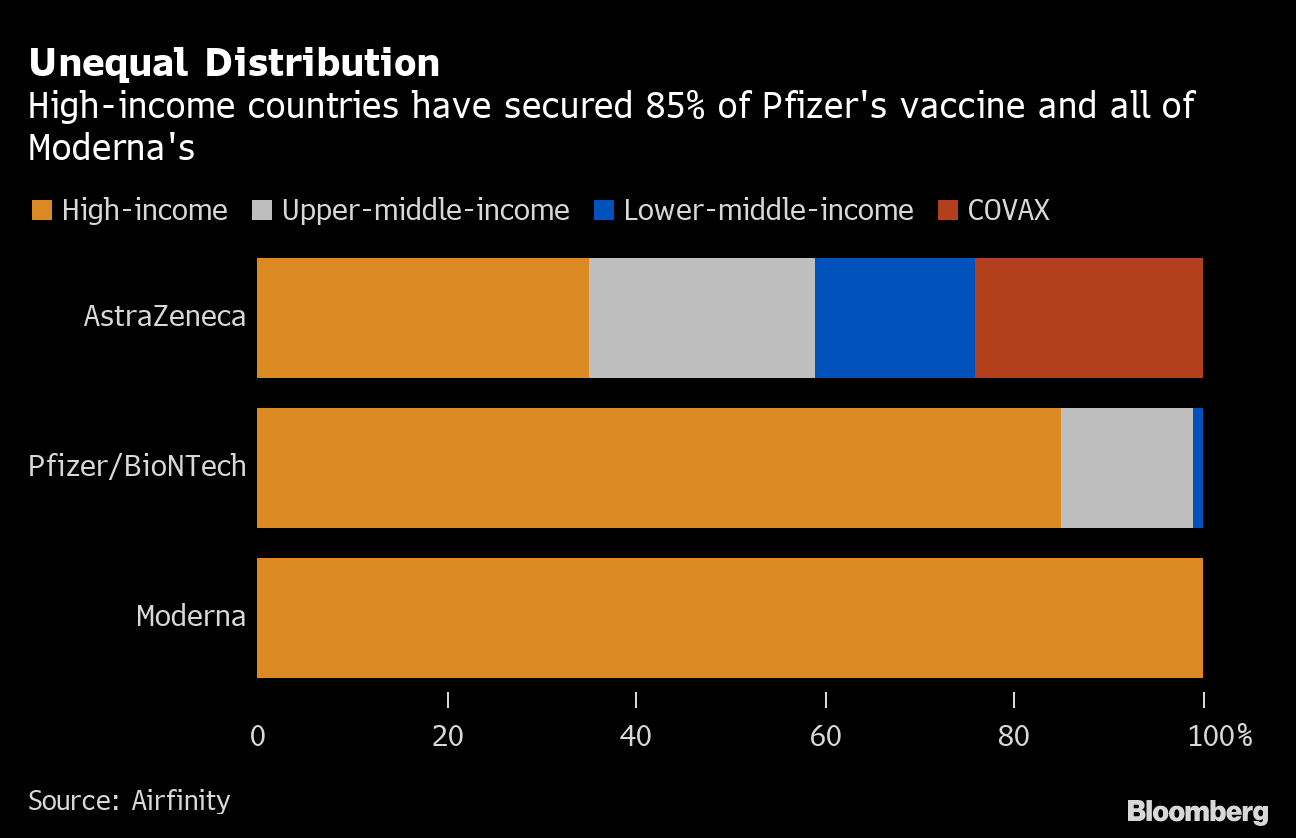

Uneven distribution

High-income countries got 85% of Pfizer vaccine and all Moderna vaccines

Source: Airfinity

Growth forecasts

“We cannot leave parts of the world without access to vaccines because it will just come back to us,” said Charlie Weller, head of vaccines at the Wellcome Health Research Foundation. “It puts everyone in the world at risk.”

Head of Immunization Programs, Wellcome, London. 2017

Photographer: Thomas SG Farnetti

Countries rely on effective vaccinations to save lives and boost businesses. the The World Bank’s projections for 4% growth this year depend on the widespread deployment of vaccines. An increase in Covid cases and a delay in the delivery of inoculations, however, could limit the expansion to just 1.6%.

High-income countries got 85% of vaccines from Pfizer Inc. and all from Moderna Inc., according to a London-based research company Airfinity Ltd. Much of the world will rely on British drug maker AstraZeneca Plc, whose vaccine is cheaper and easier to distribute, as well as other manufacturers such as Sinovac Biotech Ltd.

Read more: Africa remains with few options for vaccines, says South Africa

Out of 42 countries Deploying Covid vaccines from Jan.8, 36 were from high-income countries and the rest were middle-income, according to World Health Organization director-general Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus. A growing number of countries are pursuing their own supply agreements, in addition to participating in a global collaboration known as Covax.

Future mutants

The urgency increases as the pandemic continues into a second year. The new variants that have appeared in the UK, South Africa and Brazil appear to be spreading much faster than previous versions. Over the past month, “a new dimension of risk has opened up to the world,” said Rajeev Venkayya, president of the vaccines business of Takeda Pharmaceutical Co.

Photographer: Liz Under / Takeda

Reducing deaths and illnesses has been seen as the main driver of rapid vaccine delivery, said Venkayya, who worked in the George W. Bush administration to develop a U.S. pandemic influenza plan and led the administration of vaccines Gates Foundation.

“We now understand that it is also very, very important to control transmission,” he said, “not only to protect the most vulnerable populations, but also to reduce the evolutionary risk associated with this virus.”

While there is no evidence to suggest that the current crop of vaccines is ineffective against these variants, future mutants may be less responsive, Wellcome’s Weller said.

Drugmakers say they could tweak their plans to counter new variants in a matter of weeks if needed. The likelihood that such adaptations will be needed has increased, Venkayya said.

“The more the virus is allowed to persist in different parts of the world where we do not have a vaccine,” said Anna Marriott, health policy adviser at the anti-poverty group Oxfam, “the greater the danger of new variants which could be more aggressive, more virulent or transmissible”.

Covid vaccines have been tested for their ability to prevent symptoms, not transmission. Yet their performance in clinical trials gives an indication of their effectiveness against the spread.

Efficiency gap

The rollout of plans from Pfizer-BioNTech SE and Moderna that have achieved efficiency levels of around 95% has raised the question of whether everyone will have access to such high levels of protection.

“The divide isn’t just about access to vaccines,” said Yanzhong Huang, senior researcher for global health at the Council on Foreign Relations. “It is also a question of access to effective vaccines.”

One of the gunshots relied on by low- and middle-income countries, AstraZeneca and the University of Oxford, raised concerns in Australia it might not be effective enough to generate collective immunity. Local health officials, however, said they believed it would be comparable to injections from Pfizer and Moderna in preventing people from getting seriously ill.

The vaccine developed by British partners, introduced in the country earlier this month, provided an average efficacy rate of 70%. This appears to climb to 80% with a longer gap between doses, based on the limited data available, according to regulators. Extending this period to three months from one month allows more people to be protected more quickly, while data shows the antibody level is also increasing, a spokesperson for AstraZeneca said. .

“An optimized regimen that allows many more people to be vaccinated up front, along with a strong supply chain, means we can have a real impact on the pandemic,” he said in an e- mail.

Four very different protection rates have been published on the Sinovac shot, ranging from around 50% to over 90%. the The Chinese developer said the lower number seen in a trial in Brazil was due to the participants being medical workers at high risk of contracting Covid.

“Despite the difference in efficacy rates, they all highlight the vaccine’s protective ability, especially against medium and severe disease,” Sinovac said.

While the picture is still focused, licensed vaccines are likely to be equally effective in preventing serious illness and death, Takeda’s Venkayya said. Where they might diverge are side effects, duration of protection and impact on transmission, an even more critical factor in light of the new variants, he said.

Even shots with a lower efficiency level could have a huge impact. US regulators set a threshold of 50% to judge a candidate effective. But they would require a higher percentage of people willing to be vaccinated to get herd immunity, Huang said.

Learn more: The overall efficiency of CoronaVac in Brazil measured at 50.4%

If less effective vaccines are distributed in emerging markets, this could also have important economic implications and “accentuate the differences in pandemic outcomes between countries” Justin-Damien Guenette, senior economist at the World Bank, wrote in an email.

Many countries depend on Covax, which aims to deploy vaccines equitably to all corners of the planet. Yet not all low- and middle-income countries are waiting for a lifeline. Countries like South Africa and Malaysia are also pursuing their own supply arrangements through direct negotiations with manufacturers, and some areas should also receive Pfizer’s vaccine.

“Lose patience”

“There seem to be indications that countries are losing patience,” said Huang of the Council on Foreign Relations.

Covax has gained access to nearly 2 billion doses, with deliveries scheduled to begin in the first quarter, and set a target to vaccinate Until one-fifth of the country’s population by the end of the year. That’s a far cry from the two-thirds or more levels that many countries are targeting. Some may not get vaccinated until 2024, say the researchers.

Mobilization is accelerating. India, a nation of more than 1.3 billion people, on Saturday launched a massive vaccination campaign, an effort that is expected to meet challenges as it spreads to rural areas.

Vaccine advocates have called on rich countries to share while pushing companies to increase manufacturing capacity. Although it is early days, the trends are concerning, Venkayya said.

“Success is defined as providing vaccines to people all over the world,” he said, “and we are not yet successful in this endeavor.”

– With the help of Dong Lyu, Anisah Shukry and Michael Cohen

[ad_2]

Source link