[ad_1]

WHanging Ken Burns’ new four-part documentary on Muhammad Ali rekindled my memories of what the three-time heavyweight champion and the Nation of Islam meant to young people growing up in East Elmhurst, a residential enclave for ‘black Muslims’ in Queens.

During the 1960s and 1970s, East Elmhurst was home to an assortment of community leaders grappling with the dilemma of racial injustice. These included civil rights activists like Bill Booth, former judge and chairman of the New York City Commission on Human Rights, and NOI figures like Malcolm X, Betty Shabazz and Louis Farrakhan. .

The Burns movie, Mohamed Ali, did a good job of chronicling the usual markers of Ali’s life story, but failed to describe why the NOI would appeal to ordinary black youth at the time; instead, he shed light on the group’s “separatist” identity, “exotic” faith and uniforms, internal rivalries and unwanted statements by the organization’s speakers.

I imagine that this is normal for a cultural creation for the general public which is based on images from the national press. It’s an approach that tends to recycle old views like the 1959 CBS documentary about Malcolm X and other “black supremacists,” The hatred that hate produces. To us, however, Muslims were little more than disgruntled Baptists seeking alternative outlets.

The NOI was founded in Detroit in 1930 on the principles of freedom, justice and equality for people of African descent. In the 1960s, when I first learned about the organization, it had about 70,000 members in major cities thanks in part to the appeal of charismatic figures like Malcolm X, the national spokesperson, and Muhammad Ali.

What the documentary obscures are the symbols of cultural pride and cooperative enterprises that I remember as being remarkable to my peers. For example, members of the NOI took steps to let us know that our lives mattered without slogans and protest marches. It was common to see older men reaching out to boys in parks and on front steps to discuss history, current events, and personal goals. What did we want from life? How do we behave as young men? How are we going to contribute to the community and so on?

They discussed respecting women and family and organized street games like sprints and ball sticks. They formed neighborhood watch groups and even once recovered a bicycle that had been stolen by a white passerby. Some have told the lost story of African civilizations like ancient Sumer and Kush and the medieval empires of Ghana and the Moors. These are things we have never heard of from elementary school teachers.

Many of the former NOI had a modest education. They sometimes got the facts wrong or inflated historical achievements, but they tried within limits to instill confidence in the next generation. Some of us laughed at them for wearing bow ties, gossiping about white origins, or carrying ourselves with the strained dignity of men cast aside by society. Others of us, however, quietly enjoyed the attention of ordinary models with all their flaws.

517481124

Heavyweight boxing champion Muhammad Ali (right) sits on the podium with Nation of Islam leader Elijah Muhammad as he attends the National Meeting of Black Muslims. Ali received a standing ovation when he s ‘is addressed to the crowd at the Chicago International Amphitheater. “

Bettmann

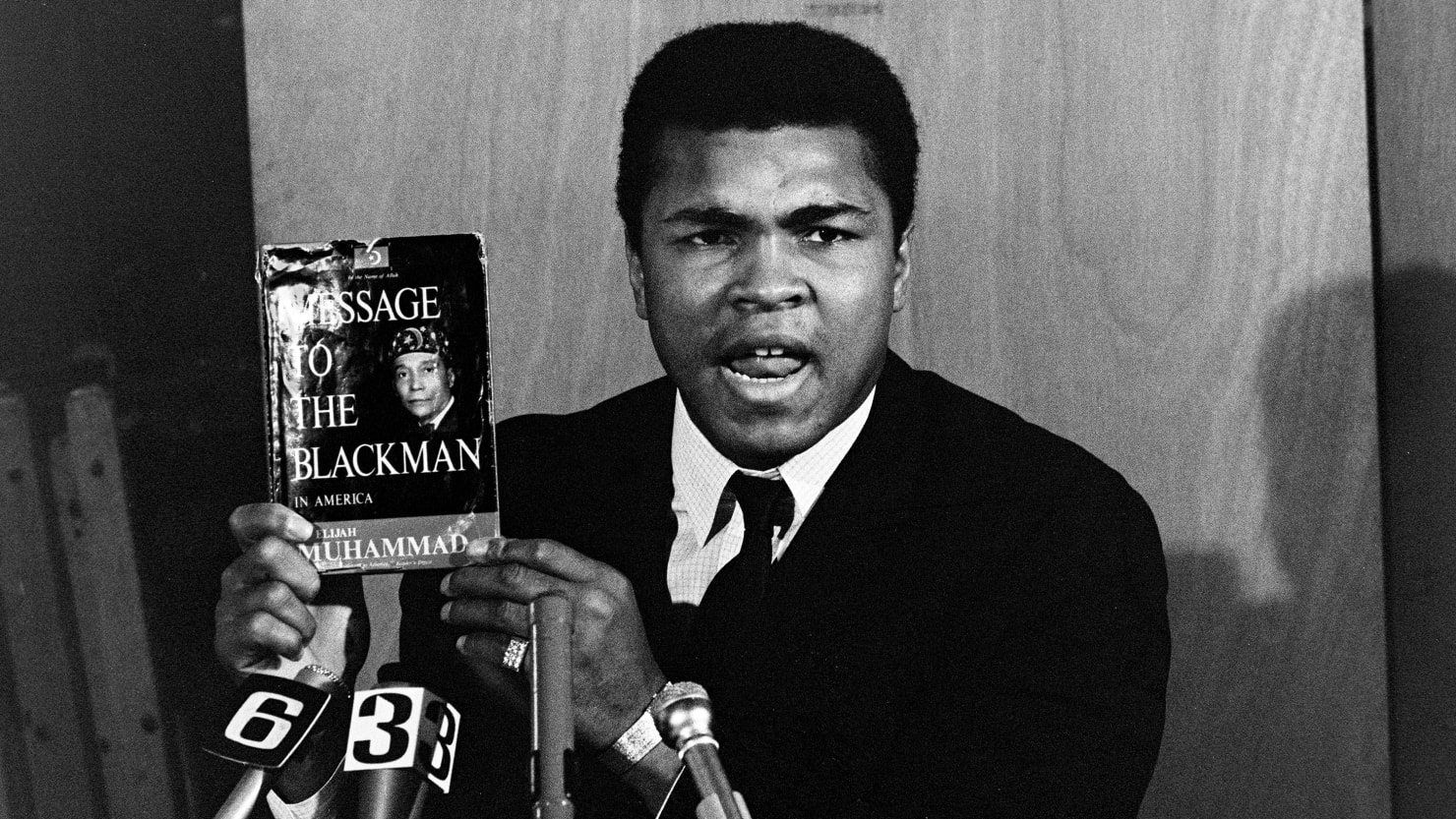

They mainly espoused the teachings of the man born as Elijah Poole, a Georgian sharecropper who was an early member of the NOI and became its leader from the 1930s until his death in 1975. He changed his name to Elijah Muhammad and distributed a “spirit mother” version in “Message to the Blackman in America”. The Burns movie showed Ali holding a copy of the 1973 artwork, but failed to explain the message or its appeal to the ordinary person.

What attracted us was not so much the message of Islam as the message of black pride, self-improvement and group cooperation. The NOI has promoted survival strategies for marginal populations in urban centers. He advocated common sense practices like living within your means, saving as much as possible, nurturing a supportive family life, spending your money between you, supporting black-owned businesses or businesses that hire your staff, and looking to improve. health, education and the community.

Such teachings have given us a blueprint for improving our chances in life. In contrast, how civil rights programs have become over-reliant on factors beyond our control: protest marches, political coalitions, passing laws, or pleading white people to pay attention to our needs. While some of these things were necessary remedies, they relied so much on positive responses from white institutions that it could foster a sense of addiction.

The NOI encouraged us to forge alliances between large black communities in urban centers and across the Pan-African world. It was a model of communitarianism that offered a more assertive basis than the strategy of incessant rallies and marches – and the NOI practiced what it preached. In the 1960s, the organization instituted an economic co-operative development program that included the purchase of farms, woodlots, housebuilding, delivery trucks, and businesses owned by individual members and the community. ‘organization.

In Chicago, for example, she opened 15 different businesses, including a clothing factory, supermarket, meat packer, bakery, restaurant, and barber shop. Across the country, he established grocery stores, clothing stores, dry cleaners, bakeries and restaurants that provided food, ready meals and clothing to the black community at affordable prices. In addition, she has hired and trained people for positions of managers, clerks, cooks, accountants, carpenters, etc.

Basically what Elijah Muhammad espoused were adaptations of Booker T. Washington’s economic development program and his National Negro Business League in 1900. Growing up in Georgia, Poole is said to have observed such initiatives at work in Atlanta and in the business districts of black communities. like Tulsa, Detroit, and Chicago.

The ideas were taken up in Harlem by Pan-Africanist Marcus Garvey and his Universal Negro Improvement Association in 1914. Elijah Muhammad adapted the idea of cooperative enterprises to the NOI, according to Claude Clegg in his 1997 biography, An original man. Moreover, he witnessed the function of such programs during the Great Depression and the incarcerated black men who ran prison services – if they could do it together, he explained, why not in their own communities. ?

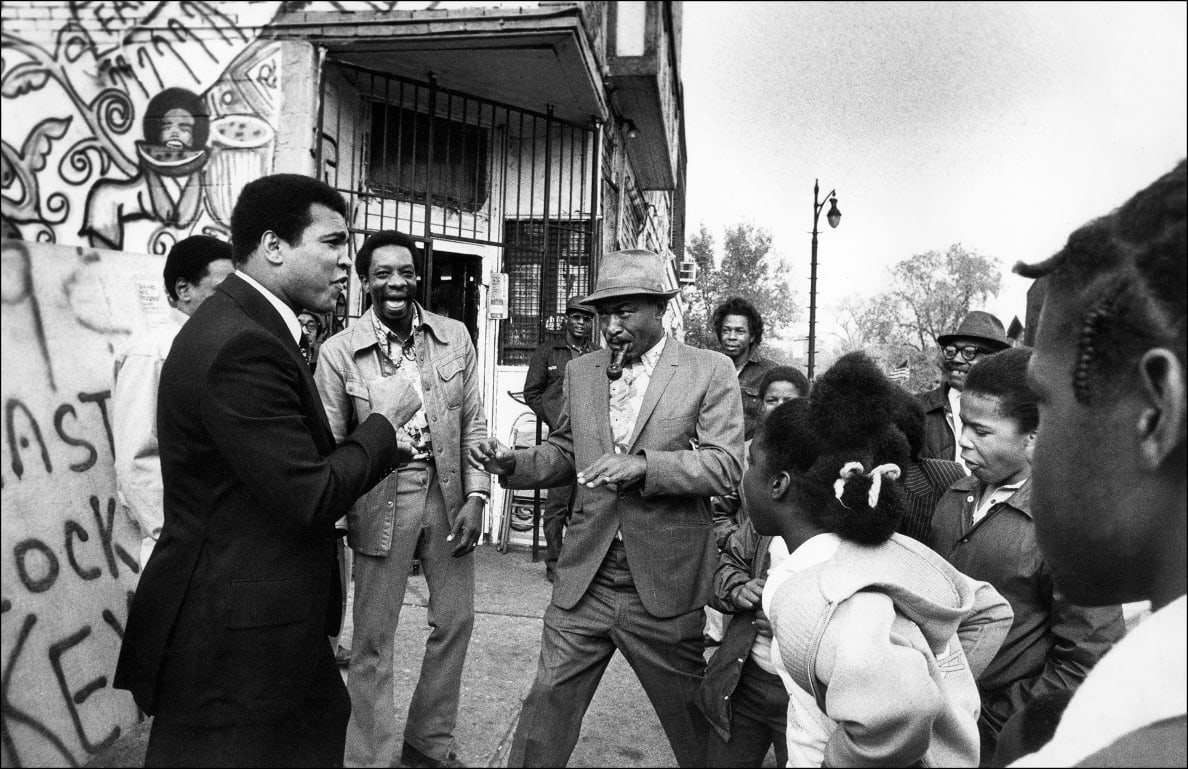

“Muhammad Ali enjoying a spontaneous meeting with his fans in Detroit, MI. Circa 1977.”

Courtesy of Michael Gaffney

Finally, the film alluded to the exploitation of Ali by the NOI to finance mosques and other operations. As young people we had no knowledge of these things, of course. However, the relationship seemed more like that of a wealthy benefactor to a favored church.

Going back to 2021, the African American political class continues to grapple with the dire conditions of its people. For the most part, they have exhausted the prospect of meaningful change through protest and can no longer claim the “diversity” of jobs and programs in government, business and institutions. For this reason, black leaders should revisit the NOI strategy for economic development that inspired Muhammad Ali.

[ad_2]

Source link