[ad_1]

Eight months after the start of the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States, it is still unclear whether two of the most promising treatments are actually working.

With a vaccine not expected before 2021, there is an urgent need for effective treatments against COVID-19. Thousands of Americans are currently hospitalized, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported projections of up to 205,000 deaths in the United States as of mid-September.

But the clinical trials needed to provide evidence of convalescent plasma and monoclonal antibodies have been fraught with delays and have had difficulty recruiting volunteers. Many trials are only starting now, months after the start of the pandemic, as researchers focused their early efforts on therapies, such as hydroxychloroquine, which were unsuccessful.

Comprehensive coverage of the coronavirus outbreak

Randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trials, considered the gold standard, assess whether a treatment works by comparing it to a placebo. Initially, neither the researchers nor the participants know who gets the real thing and who gets the placebo.

This created challenges for the researchers performing the trials.

“There are people who say, ‘I don’t want to be a guinea pig. If you think this stuff works, why not give me the real stuff? “As opposed to a placebo,” said Dr. Shmuel Shoham, an associate professor of medicine in the division of infectious diseases at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine.

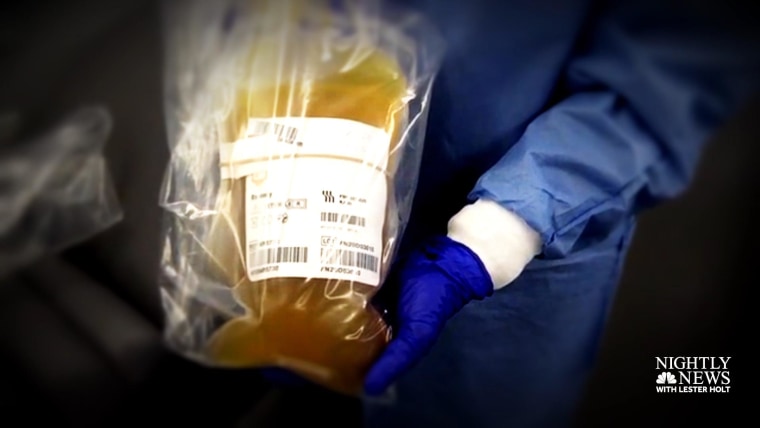

The idea behind convalescent plasma and monoclonal antibodies is to give the immune system a boost to fight the virus. Convalescent plasma refers to the antibody-rich blood product taken from patients who have already recovered, and monoclonal antibodies are a synthetic version of these antibodies that could be mass produced in a lab.

But tens of thousands of COVID-19 patients who may have been eligible for clinical trials evaluating these therapies have already received convalescent plasma as part of the expanded access program run by the Mayo Clinic, putting them out of the race. to be a trial participant.

“Some of us quickly jumped on this bandwagon,” said Dr Ashok Balasubramanyam, vice president of academic integration and senior associate dean for academic affairs at Baylor College of Medicine, citing early evidence from from China suggesting a therapeutic benefit for recovering plasma.

“The program was very liberal,” Balasubramanyam said. “Anyone can log on and get FDA approval fast.”

This isn’t necessarily a bad thing during a pandemic in which millions of Americans have been infected. Convalescent plasma has a long history of use for other illnesses and is generally considered safe.

While this is unlikely to hurt, and could actually help, many patients choose to obtain plasma.

Shoham and his colleagues at Johns Hopkins are conducting a nationwide clinical trial to find out whether convalescent plasma can either prevent disease or keep infected people healthy enough to stay out of hospital.

But less than 100 participants out of the expected 1,000 have registered so far.

A study site in Florida had to shut down, Shoham said, as clinical research coordinators became too overwhelmed to deal with COVID-19 patients. Others have struggled to find a suitable space certified by a blood bank to do the infusions.

“We have been caught off guard by this virus,” Shoham said. “It took us a while to get back on our feet.”

Plasma for hospital patients

The National Institutes of Health gave $ 34 million to Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville to conduct a large-scale randomized controlled trial to determine whether convalescent plasma can help critically ill patients hospitalized with COVID-19.

“We have been told to get this answer as quickly as possible,” said Dr. Todd Rice, associate professor of medicine at Vanderbilt. Up to 1,000 patients will be recruited from 50 sites across the country. Rice will lead the monumental effort.

“Convalescent plasma is not the easiest thing to come by. It is a blood product, and ideally it has to go through tests to make sure the patient has the right antibodies that will actually neutralize the virus. Rice said. “It’s not quite like saying, ‘Here’s a drug. Take it. “”

Federal researchers are closely monitoring clinical trials. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration is reportedly considering issuing an emergency use authorization for convalescent plasma, a move that would expand the ability of physicians to access the product.

“In accordance with the policy, we are not in a position to say whether or not we will take any action regarding the emergency use authorization for convalescent plasma and render a decision at the appropriate time”, Dr Anand Shah, Commissioner FDA assistant for medical and scientific affairs, said in an email.

“Science is really important because we have taken some wrong turns in the last few months,” said Balasubramanyam. The FDA had to revoke an emergency use authorization for hydroxychloroquine in June, after evidence showed the drug carried too many risks and did not work to treat COVID-19.

With the convalescent plasma, Balasubramanyam said, “We have a clue that it is working. Now, it is extremely important that we be sure that it is working.”

The results will depend, in part, on people’s willingness to volunteer for randomized clinical trials. This means that a patient can be assigned to receive a placebo, rather than the real antibody-rich plasma.

Kellie Guyton, 34, of Winfield, Alabama, knew she would need specialized care when she was hospitalized with COVID-19 in July. Previous heart surgeries and a kidney transplant put her at a higher risk of complications from the coronavirus.

But Guyton chose to participate in the trial at Vanderbilt.

“I thought if that didn’t affect me negatively, I was all for it,” Guyton said. “It’s a chance to help the next person down the line. It could be your grandmother, your neighbor, or your best friend.”

Monoclonal antibodies

The supply of convalescent plasma relies on enough people who have recovered from the virus to take the time to donate and is therefore a limited resource.

This is where monoclonal antibodies might come in handy. Scientists collect convalescent plasma, focus on the strongest and most specific antibodies to the coronavirus, and then replicate them in a lab in large quantities.

Several drug makers are developing monoclonal antibodies, including Regeneron and Eli Lilly. The two companies began clinical trials in early June. But the results of two of those trials, conducted by the National Institutes of Health, won’t come until later this year.

The Human Vaccine Institute’s Pandemic Prevention Program at Duke University recently announced that it will also develop and study a monoclonal antibody to prevent infection with SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19.

It is not known how long such protection would last. The aim would be to give it to people belonging to high-risk groups, such as those in long-term care facilities, doctors, nurses, even National Guard troops, if they need to help in areas of high infection.

Download the NBC News app for comprehensive coverage of the coronavirus outbreak

It is far from being used in the clinic. Researchers hope to start recruiting patients next spring.

“We have to go through the preclinical safety and efficacy studies,” said Gregory Sempowski, who is leading the trial. “It just takes time. We’re doing it on a much faster schedule than we’re used to.”

All of these research projects require a careful balance between respecting the scientific process which can be time consuming and understanding among investigators that they must act faster than the coronavirus, which has sickened nearly 6 million people in the United States. United. and killed more than 175,000 Americans.

“It is important that the public understand this scientific approach to treatment,” said Balasubramanyam. “It is also important that scientists understand the need for speed.”

Despite early delays, Shoham hopes that convalescent plasma trials will gain momentum soon.

“I think that in a few strong weeks we will be much further ahead,” he said. “So hopefully we get an answer for the doctors, for the patients, for the families, for the FDA.”

Follow NBC HEALTH on Twitter & Facebook.

[ad_2]

Source link