[ad_1]

The buried oceans, like the one that would believe under the icy surface of the Pluto dwarf planet, can be incredibly common in the cosmos.

A new study indicates that the layer of gaseous insulation probably prevents Pluto's liquid ocean from freezing. And something similar could happen beneath the surface of icy worlds in other solar systems, said members of the study team.

"It could mean that there are more oceans in the universe than previously thought, making the existence of extraterrestrial life more plausible," he said. Lead author Shunichi Kamata, of Hokkaido University in Japan, in a statement.

Pluto's "heart" alludes to a buried ocean

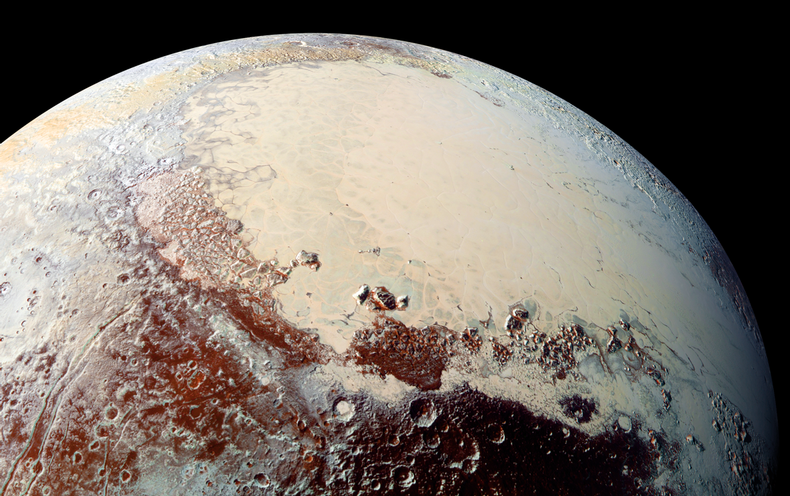

Arguments for an underground ocean in Pluto are reinforced by the location of Sputnik Planitia, a 600 km wide (1000 km) nitrogen ice plain that forms the left lobe of the famous "heart" of the dwarf planet.

Observations from NASA's New Horizons probe have shown that Sputnik Planitia is aligned with Pluto's tidal axis, the most powerful line for pulling the gravitational pull of Charon, the largest moon on the dwarf planet, is more powerful. Scientists believe that Pluto has entered this orientation because of the extra mass concentrated at the surface and near the surface in the Sputnik region Planitia.

This additional mass probably comes from the accumulated nitrogen ice in the plain, as well as from the buried ocean water, which was released to rise from the basement after the impact. from the comet that formed Sputnik Planitia broke the crust at this place. Previous research suggests.

But how could a buried ocean stay thawed on Pluto during the 4.6 billion years of the solar system's history? After all, the dwarf planet does not surround a gas giant, so its entrails are not shaken and heated by the tidal forces as dramatically as the interior of Jupiter's moon, Europa, and Saturn's satellite, Enceladus, also harboring underground oceans.

The new study offers a possible explanation. Kamata and his colleagues hypothesized that an insulating layer of "gas hydrates" – ice-like solids composed of gases trapped in molecular water "cages" – under Pluto's ice shell could to be responsible, then proceeded to computer simulations to test the idea.

During simulations performed without gas hydrates, the Pluto Ocean froze hundreds of millions of years ago. But with the insulating layer, the ocean still persists today, researchers discovered. Gas hydrates also act as an insulator in the other direction, helping to keep Pluto's surface cold enough to withstand the observed variations in ice shell thickness, the researchers said.

It is not known what the gas in the water cages could be (if such a layer actually exists). However, the study team believes that methane is a good candidate, partly because Pluto's sneaky atmosphere lacks substance.

The new study was published online today (May 20) in the newspaper Nature Geoscience.

Copyright 2019 Space.com, a future society. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, disseminated, rewritten or redistributed.

[ad_2]

Source link