[ad_1]

Header (a hand holding a smartphone opening the Uber app). Credit: Carnegie Mellon University

A new study by Ph.D. Jacob Ward, Jeremy Michalek Professor of Engineering and Public Policy (EPP) and Mechanical Engineering (MechE), and Costa Samaras Associate Professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering at Carnegie Mellon University quantifies the costs and the benefits of traveling with a transportation network company (TNC), such as Uber or Lyft. They found that a TNC trip on average decreases local air pollution compared to driving a personal vehicle.

“When a vehicle first starts up, it produces a high level of harmful air pollution until its pollution control system warms up enough to be effective,” Michalek explained.

An earlier study by university professor and department head MechE Allen Robinson and others found that for some pollutants, emissions from a single vehicle were equivalent to those from hundreds of miles of high-temperature trips. “Given that an Uber usually arrives hot when it comes to pick you up, we wondered if it could offer any clear air quality benefits over starting a personal vehicle for the same trip. “Michalek said.

To answer this question, the team collected data on TNC vehicles and personal vehicles and modeled the air pollution consequences of vehicle starts and hot vehicle trips, as well as the additional trips of vehicles. TNC enters trip requests. “TNC vehicles tend to be newer,” Samaras explained, “so they were built to meet more stringent pollution standards. ”

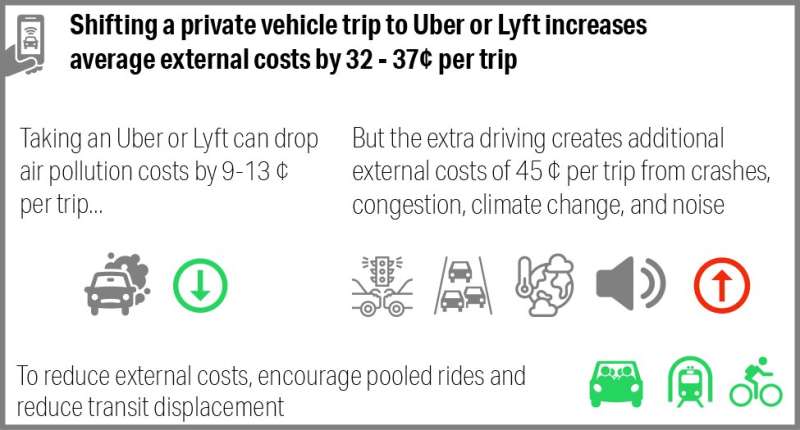

Putting these factors together, the team found that, on average, a TNC trip produces only half the local air pollution costs of a personal vehicle trip, thus reducing pollution-related health costs. of air about 11 cents.

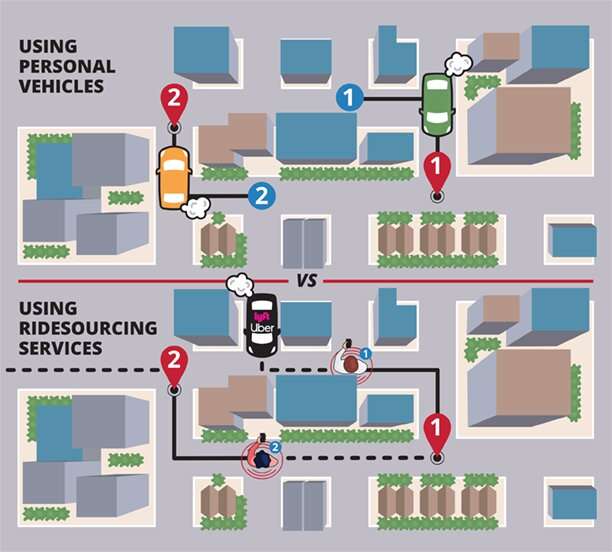

The diagram shows how TNC vehicles create less air pollution but spend more time driving. Credit: Carnegie Mellon University

However, the team showed in their study that additional road trips from TNC vehicles also have major drawbacks. TNC drivers spend a large portion of their time driving between passenger pickups or waiting for new ride requests, known as one-on-one. This extra driving means that a TNC’s fuel consumption – and by extension its greenhouse gas emissions – are on average about 20% higher than a personal vehicle.

More time on the road also means more congestion, more noise and more risk of traffic accidents. Taking all of these factors into account, the team found that opting for a TNC over a private vehicle increases external costs to the company by 30-35%, or about 32-37 cents per trip. This burden is not borne by the individual user, but rather has an impact on the surrounding community. Society as a whole currently bears these external costs in the form of increased mortality risks, damage to vehicles and infrastructure, climate impacts, increased traffic congestion, etc.

By testing other scenarios, the team found that if the TNC ride was pooled (shared with another rider doing another ride in the same direction), the external costs could be lower than a ride by personal vehicle. But if the TNC journey replaces a public transport journey instead of a personal vehicle journey, the external cost implications triple.

A graph weighs the trade-offs between air quality, emissions and safety in the use of TNCs. Credit: Carnegie Mellon University

Michalek and Samaras hope that by quantifying these unspecified costs to society, they can give decision-makers the information they need to develop policies that redirect external costs from the public at large to the private actors that generate them. Data like this could also prove useful in finding ways to maximize the potential benefits of TNCs while minimizing external costs.

“If you want to cut costs for others on your TNC trips,” Michalek said, “you’d better choose a bundled ride when you can and use public transportation when available.”

Uber and Lyft increase average vehicle ownership in urban areas

Jacob W. Ward et al, Air Pollution, Greenhouse Gas, and Traffic Externality Benefits and Costs of Shifting Private Vehicle Travel to Ridesourcing Services, Environmental sciences and technologies (2021). DOI: 10.1021 / acs.est.1c01641

Provided by Carnegie Mellon University, Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering

Quote: Who pays for your Uber? (2021, September 21) retrieved September 22, 2021 from https://phys.org/news/2021-09-uber.html

This document is subject to copyright. Other than fair use for private study or research purposes, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is provided for information only.

[ad_2]

Source link