[ad_1]

MARK RALSTON / AFP / Getty Images

MARK RALSTON / AFP / Getty Images

NOTE: This is an excerpt from Planet Money's newsletter. You can register here.

In recent months, many studies have denied the predictions that we are witnessing the dawn of a new "entertainment economy". The US Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) found that there was in fact a decline Larry Katz and the late Alan Krueger then reviewed their influential study that he was at the origin of the explosion of work together. Instead, they found that growth had been modest. Other economists have come to find the same thing – and now, writers say that the economy of the show is "a big nothing more".

The true believer of the gig revolution

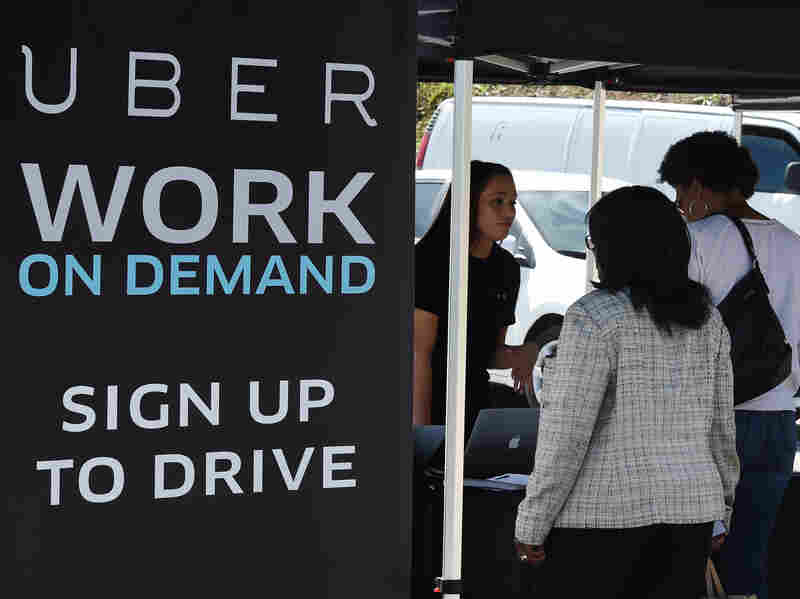

Arun Sundararajan, NYU economist and author of The sharing economy: the end of employment and the rise of capitalism based on the crowd, remains a staunch supporter of the concert revolution. Sundararajan defended the idea that the economy of the show – and more specifically the work done on digital platforms such as Uber and Airbnb – would conquer traditional employment. Instead of an economy dominated by big business, he thinks it will be dominated by "a crowd" of independent contractors and workers transacting with customers via digital platforms. "We are in the early days of a fundamental reorganization of the economy," said Sundararajan while traveling to the airport, naturally, in an Uber.

When asked about the data attack contradicting his thesis, Mr Sundararajan said that the Bureau of Labor Statistics continued to "underestimate the size of the mass retail economy, and in particular that of the platforms. " The BLS's best estimate of the number of agency workers employed on digital platforms – full-time, part-time or casual – is 1% of the total US labor force, or about 1.6 million workers in mid-2017. Sundararajan claims that the survey questions used by the BLS to collect this data were clumsy and did not accurately reflect what was happening.

While Sundararajan does not agree with the estimates on the size of the market economy, it should be that most people doing new work are Uber and Lyft pilots or Airbnb hosts . It is not a coincidence that housing and transportation have been the two main areas of growth. Homes and cars are the most valuable assets that many people have. Internet and smartphones make their use considerably easier. Sundararajan argues that there will be growth in areas such as health care and accounting, but there is little evidence to suggest that we are witnessing "the end of employment".

The resilience of traditional employment

Employment as we know it is a relatively new development. At the turn of the twentieth century, nearly half of Americans were still independent as farmers, pastoralists and artisans. But in the background, a powerful organization called the company was taking off. In 1960, about 85% of Americans were employees of corporations.

Sundararajan believes that our economy will once again be dominated by the self-employed, but he admits that full-time employment presents "a multitude of benefits". It offers stability, a regular salary and benefits. We have collectively designed a large part of our social safety net to participate in this system. All this means, said Sundararajan, "we will see a full-time job remain resilient, even if there are more efficient ways to organize the economic activity". He thinks that work done on concert platforms can be more effective than work done in a traditional business – and that will mean his loss.

The mysterious benefits of the business

Economists have long been puzzled by the existence of businesses. They celebrated the awards and the competition – and it seemed natural that the most effective way of doing business would be as an individual trading in the open market. Need an advertiser? Rent one for a few weeks. You want design work? Work for the highest bidder until the end of the project.

From this traditional perspective, it seemed odd that we organized ourselves as full-time employees in top-down bureaucratic organizations isolated from the market. Then came Ronald Coase, who won the Nobel Prize in 1991, largely because of his 1937 article entitled "The Nature of The Firm". Coase argued that the reason businesses exist is that market transactions are expensive for individuals. You must look for trustworthy people with quality goods or services, and then negotiate with them, and this over and over again is ineffective. According to Coase, these transaction costs are minimized within a company. You can quickly go to your colleague's office and share ideas without having to decide if they are suspicious. You can share resources, tools and machines. You can work in a team and specialize in different tasks. And you can do all this without having to continually negotiate the price of everything.

The dawn of a new concert economy seemed plausible as the internet has dramatically reduced transaction costs. Search engines have made it incredibly cheap to search for goods and services, compare prices and find bargains. Social media and peer reviews have made it easier to determine if people are trustworthy. E-commerce facilitates the processing of payments. You can click a button on a mobile phone and instantly get the GPS guide drivers. But as important as these gains in efficiency have been, a new economy based on a crowd of people doing concerts on digital platforms – as exciting or frightening as it may seem – still does not compare to an economy based on the efficiency and stability of the good old fashionable business.

Did you like this newsletter? Well, it looks even better in your inbox! You can register here.

[ad_2]

Source link