Working notes.

It was a bad sign. The day the vote began at the Volkswagen plant in Chattanooga, Tennessee, the shift change suddenly turned blue.

Crowds of workers were crossing the mill's turnstiles in both directions at the end of the day and night. In the previous days, activist handles in bright green shirts were there to distribute leaflets and jokes to their colleagues.

But on Wednesday, instead of angry union activists, an ocean of workers went through the turnstiles wearing the anti-union blue shirts "A Team: I'm Volkswagen" provided by the company.

Only a few workers wore United Auto Workers shirts. Union supporters were visibly 20 times less than supporters.

This scene was a warning of what was coming. Friday night, the votes were counted and the union lost in another tight vote heartbreaking, 776 yes to 833 no. Ninety-three percent of eligible workers voted.

Missed opportunity

What is it that did not go well? Obviously, the 1,700 production workers who voted every hour were subjected to a brutal election campaign, contrary to the neutral posture studied by VW in the 2014 campaign, which the union lost by a narrow margin.

This time, although Volkswagen continued to be neutral, the factory's supervisors were determined to scare and cajole the workers to vote no.

Meanwhile, outside the factory, workers had to face a new wave of dam in 2014. Business-supported astroturf groups flooded the airwaves and television with ads attacking the UAW. State politicians have threatened to withdraw their support for state incentives related to the upcoming expansion of the plant and the production of a new electric vehicle.

As terrible as these attacks on workers were, they were also predictable. Why does not the union have a plan to defeat them?

On the basis of conversations with dozens of pro-union employees, it is clear that the union did not organize a high-profile campaign in the factory, able to withstand the fierce struggle of business leaders.

Although the union spent tens of thousands of dollars on radio and television ads, it also did not carry out any substantive campaign to pressure society. Nor did it attempt to organize and take advantage of the much smaller number of workers at nearby Volkswagen parts suppliers, where a well-placed action could put an end to the entire VW plant.

And while the boss's anti-union tactics were commonplace, the workers were not warned. Inoculation about what to expect, including a "Mr Nice Guy" from society, should be the norm in any trade union action. (See box for examples of how other unions have defeated the tactics of their authors.)

U turn of VW

Volkswagen turned back on organizing in 2015 after an expensive scandal.

It appeared that the company had installed software on 11 million "clean diesel" vehicles, which allowed them to successfully pass emission tests despite the release of toxic gases up to 40 times over. beyond the legal limit.

Since then, many leaders have been tried in criminal cases and the company has paid $ 30 billion in fees after several countries filed lawsuits.

According to a 2015 study by the Center for American Research, the average salary and benefits of workers at the Chattanooga plant are the lowest of all US plants.

Revealed by the financial sinking of the "dieselgate", Volkswagen's management wanted it to stay that way.

Under pressure

In early April, workers demanded union elections. The union was hoping for an election by the end of April – but Trump labor board maneuvers delayed voting until mid-June.

VW had previously hired the well-known law firm Littler Mendelson, which breaks unions, to curb the election of 160 skilled workers by 2015. The company refused to bargain with this new bargaining unit and the case has spent years in the courts.

Eventually, the UAW abandoned the skilled trades unit – but not until Littler Mendelson used it as the basis for a court challenge to the new union petition.

The company took full advantage of these additional six weeks to distribute threats and rewards.

The managers have made a series of improvements. They began to cool the factory earlier in the week, changed the wardrobe policy to allow shorts, changed the weekly schedule from five to eight hours and four to ten o'clock and fired several directors, including unpopular factory CEO Antonio Pinto.

The union should have proclaimed these improvements as the workers won their first victories: look how powerful you are and you have not even arrived at the table yet! This is not the case.

Management also began using mandatory morning meetings as an opportunity to distribute anti-union leaflets. Workers who dared to wear pro-union stickers and UAW brand safety glasses were forced to remove them, and did so. Security guards were sent to harass workers who distributed leaflets in the car park.

Tennessee's governor, Bill Lee, led his own anti-union meeting in the factory on April 29, when the UAW hoped the elections would take place. Two days later, the news bulletin read aloud that the $ 50 million profit-sharing agreement related to the expansion of the plant and the new electric vehicle line was still "subject to final agreement with the administration of Governor Lee ". The workers took this as a threat.

The supervisors also distributed a pamphlet insinuating that a vote for the union was a vote for the closure of the plant – a point that general manager Frank Fischer had also criticized during captive hearing meetings of all the factories that he had directed at the end of May.

Launch error

The anti-union tactics of society were horrible, but also tariffy. VW has behaved in much the same way as most US employers when workers are trying to form a union.

Attacks by outside groups and politicians are not so common. But it was the second round and the barrage looked a lot like what the union had to face in its previous fruitless efforts at this plant. The same thing happened during the UAW campaign at Nissan in Mississippi and that of machinists at Boeing in South Carolina. At least in the South, we should expect it from now on.

In other words, the UAW is not flawless. The union did not set up a combat organization at the shop floor – that's what it takes to win an election under that kind of pressure.

"There was no organization to bring people together," said a seven-year-old production worker who asked to remain anonymous. "They said if we started petitioning and winning on issues, there would be less demand for a union.

"So it all boiled down to supporting the UAW plan, not to rally the workers to support each other."

The strategy of the UAW depended on the holding of fast elections: the partisans hoped to be able to vote a few weeks after the filing of the petition. This would have minimized the impact of the company and anti-union groups, which were caught off guard.

"Volkswagen did such a good job of screwing up so many areas of the plant that there was a lot of reluctant momentum for a union," said the same worker, "not because they like the UAW, but because they think only way to change things for the better. "

But the support was not powerful enough to withstand months of heat from society.

No climbing plan

In a strong union campaign, organizers help workers identify the leaders in the workplace that others respect most and recruit them into the organizing committee.

The committee identifies workplace issues that are deeply and widely felt in the factory – such as endemic injuries due to high turnover and high line speed – and encourages colleagues to take collective action to launch a challenge to the company.

For example, during the 2008 UFCW Campaign to organize 5,000 workers at the Smithfield Food, North Carolina slaughterhouse, activists resorted to collective action to get the union out there. in the factory even before having won the elections.

The organizing committee has asked more than 1,000 workers to wear union shirts at the factory. They held public hearings at which the workers spoke about the harsh conditions in the factory and the injuries they suffered. They prepared for an action in which 1,000 workers left work, closed the lines and held rallies with the community in front of the factory.

A day-long strike in the livestock department – a turning point in the production process that has shut down the rest of the business – has led workers to secure serious concessions and boost activism among the rest of the factory. The activists also led union meetings in the cafeteria during lunch, during which the workers discussed issues and chanted.

Actions like these help workers gain self-confidence and self-esteem and a sense of collective power. They prove that management and employees do not have the same interests, despite all the rhetoric of the "one team" – and that the boss does not hold all the cards.

They also provide the organizing committee with a much more realistic assessment of who will vote for the union. It's one thing to sign a card in the privacy of your living room or tell an organizer on the phone what he wants to hear.

It is another matter to publicly wear a sticker, hand out leaflets in front of the turnstiles, attend a union meeting at the cafeteria during lunch, or sign a petition and leave with a group to hand over to the boss. Someone who does these things is much more likely to maintain their union support under intense pressure.

According to pro-union activists, the UAW thought it had a clear majority determined to vote yes. But these evaluations clearly did not resist. Most were based on conversations and not on collective actions.

Scattered participation

There was a handful of actions, but no systematic campaign. And participation was low – which sent the wrong message, showing the union's vulnerability.

"Some people wear shirts, buttons and stickers, but the number of people who have signed cards is far from the same," said Mark Dougherty, assembly line worker, in an interview a few weeks ago. before the elections.

Several members of the organizing committee have said that the highlight of the activity at the factory was when 30 to 40 workers handed out leaflets at the main entrance and then came in together.

Some had hoped to beat that record on Tuesday – the day before the vote began and the day after the company's last meeting with a captive audience. Only a dozen workers in UAW shirts have arrived.

"The people here are scared. They are afraid of their supervisors. Fear of the closure of the factory, "said another worker who asked not to be identified for fear of retaliation from management. "Many think it's the best job they have or can get. So I think most people can be afraid of not voting.

Roads not taken

After the 2014 elections, local organizers and union activists drew attention to another factor contributing to the union's loss: the UAW had not waged a serious campaign to implicate the union. community in the union struggle. The same thing was true this time.

The only pro-unionist community event was a gathering in downtown Chattanooga, hastily assembled and despite the reluctance of the UAW. About 70 people showed up. On the other hand, the "family day" of the management at the factory attracted 5,000 people the week before the elections.

Public pressure on an employer can be a deterrent, discouraging some of the worst anti-union behavior.

For example, as teachers began their recruiting drive in a Chicago-based charter school, the union quietly approached influential leaders in the community who had connections with the CEO and board members, and provided support.

The day the teachers walked with their directors to publicly announce their union campaign, these allies began to call the company with the following advice: Be reasonable. Do not go to war. A few days later, the CEO fired the unionist he had hired.

In Smithfield, the union asked local churches, football clubs and civil rights advocates to show workers: "We are with you". He also organized public hearings on labor rights violations and large public gatherings that drew national media attention. Horrible conditions in the factory have become synonymous with the Smithfield brand, which has had a negative impact on society.

The UAW could have organized a national solidarity protest campaign at Volkswagen dealerships to inform potential consumers of the company's environmental scandal and anti-worker record. Control may have tempered VW's activities and public support could have given workers a boost.

Instead, the union spent nearly $ 50,000 on radio and television ads to deal with the aggressive air war on the other side. Arriving in the factory, you pass in front of billboards alternating pro-trade and anti-union messages. If you turn on your radio, you will hear advertisements from both sides. The union even had video messages about the pumps at gas stations near the factory.

The total effect was deafening; people just wanted everything to end. It is not the atmosphere that wins the union elections.

Forgotten leverage effect

Nor was there any attempt to flex the structural power of the workers.

Like other foreign manufacturers, Volkswagen relies on grouped parts suppliers near the factory (some are within a few minutes walk) to facilitate rapid transportation. These suppliers do not store parts; instead, they produce them quickly, on demand.

Thanks to this just-in-time production system, foreign manufacturers have gained a considerable competitive advantage over the three major national manufacturers. The Big Three have abandoned such a system because of its critical vulnerability: it can give workers considerable power over society.

"There are parts factories that produce the huge mass of parts for cars being assembled," said Joshua Murray, a specialist in power and corporate behavior at Vanderbilt University. "If you close these factories, then all production will be affected."

And if the UAW had started by organizing these parts factories? The number of workers is much smaller. A class action could stop the production of the entire Volkswagen plant and allow the company to obtain concessions. The concrete example of effective activism would inspire Volkswagen workers more than a hundred television ads.

"What is important to remind workers is that the union is made up of workers and it is their influence in the system that gives them power," said Murray. "And even if the union leaders do not know it, you can act without them.

"Businesses depend on workers to function, and if you can find the most effective way to prevent your cooperation, you can beat anyone."

A losing record

The continued losses of the UAW in the south are not a reflection of the workers who live there.

These losses are the result of extremely sophisticated and intense anti-union campaigns by employers, business groups and politicians.

They are also the result of the unsophisticated and shallow organization of the UAW.

Even if the union had won the elections, its weak and conflicting organizational approach raises serious questions about whether it could have won a first contract – or a good one.

The UAW should tackle such a union campaign as the fight of his life. We must leave nothing to chance. He should fight with the same courage and tenacity as the workers who organize themselves.

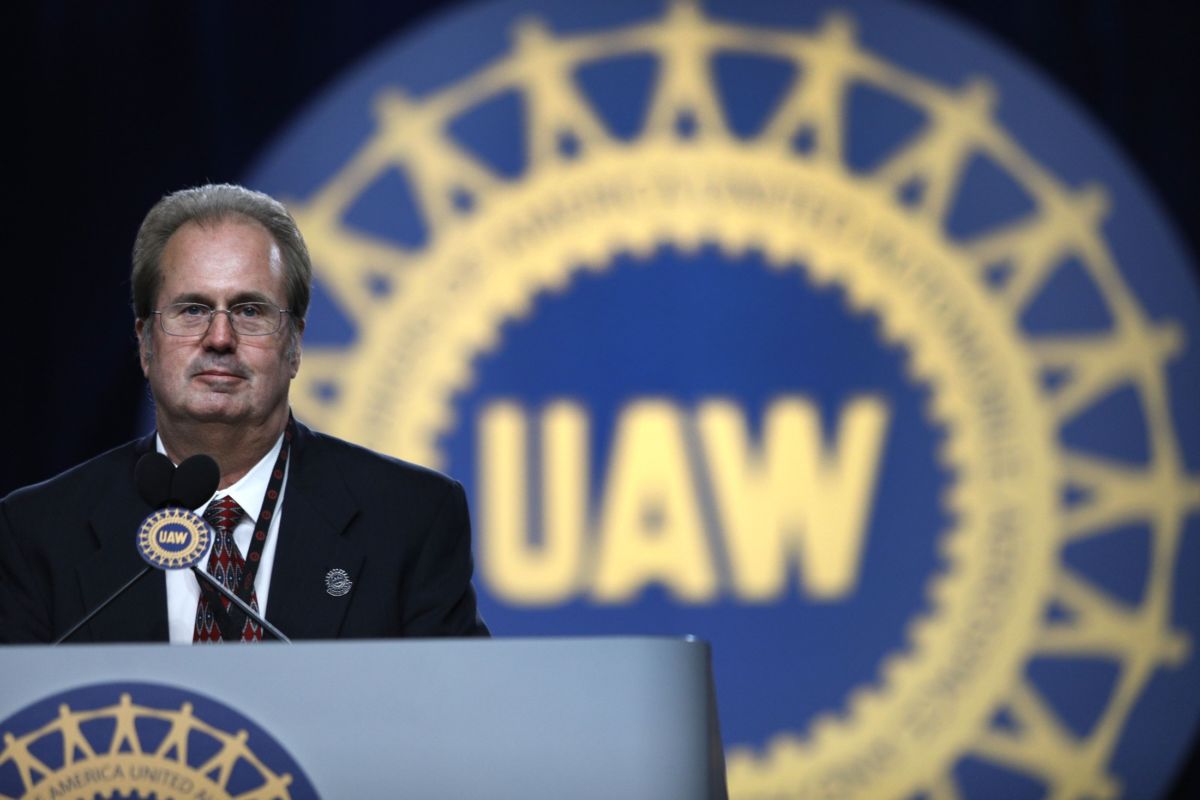

As revealed by the charges in the Chrysler bribery scandal, the company's leaders encouraged union leaders to secretly pay in their pocket the money from the jointly run training center. According to the Ministry of Justice, the company's goal was to keep union leaders "big, dumb and happy".

The UAW's long-term commitment to a "partnership between workers and management" is at the root of the corruption scandal, but also of the union's ruthless and ineffective unionization. Both must be washed away.

Unfortunately, none of this will likely occur in the absence of a basic reform movement aimed at turning the union up and down.

New Labor Notes book: The secrets of a successful organizer is a step-by-step guide to gaining power at work. "It's full of creative examples and compelling stories that make you want to dive right now." Buy one today for only $ 15.