[ad_1]

Increasingly fierce wildfires in the western United States are devastating the region’s air quality, new study says, with smoke from wildfires now accounting for half of pollution atmospheric during the worst years of forest fires.

Scientists at Stanford University and UC San Diego have found that toxic smoke plumes, which can blanket Western states for weeks when wildfires rage, are reversing decades of reduction gains air pollution. While heat-related deaths were previously considered the worst consequence of the climate crisis, researchers say air pollution from smoke could be just as deadly.

“For a lot of people in this country, wildfires are going to be how they experience climate change,” said Marshall Burke, associate professor of earth sciences at Stanford and one of the study’s authors. “The contribution of forest fires to poor air quality has almost doubled over the past 15 years in the west.”

Air pollution from fine particles, known as PM2.5, was already known to reduce the lifespan of the average American by four months. And health researchers are only just beginning to understand the terrible health consequences added by increasing exposure to smoke for large swathes of the American population.

The wildfire seasons have become increasingly brutal in the American West, exacerbated by the climate crisis. The 2020 firestorms were among the worst in recorded history, with 31 people killed, 10,000 buildings destroyed or damaged and more than 4 million acres burned in California alone. Large swathes of Colorado, New Mexico and Arizona were also burned.

After residents of California endured a month of orange-brown air filled with tiny dangerous particles, another group of Stanford researchers tracked dramatic increases in hospitalizations for reasons like strokes, heart attacks and asthma.

Bibek Paudel, a postdoctoral researcher at the Stanford Asthma Clinic, found that hospitalizations for stroke and related conditions increased by 60% in the five weeks following the start of the lightning-induced fires last August. The number of lost pregnancies also doubled in the weeks following the fires – a startling finding that researchers continue to interpret. Paudel also found a significant increase in heart attacks and hospitalizations among young people for respiratory disease.

“I don’t think people are aware of the long-term health effects of wildfire smoke,” said Mary Prunicki, director of research at the Sean N Parker Center for Allergy & Asthma Research at Stanford.

For decades, the air quality in the United States has improved thanks to the reduction in pollution from cars and factories, mandated by the Clean Air Act. But over the past 40 years, the amount of land burned in forest fires has quadrupled, according to Burke’s study.

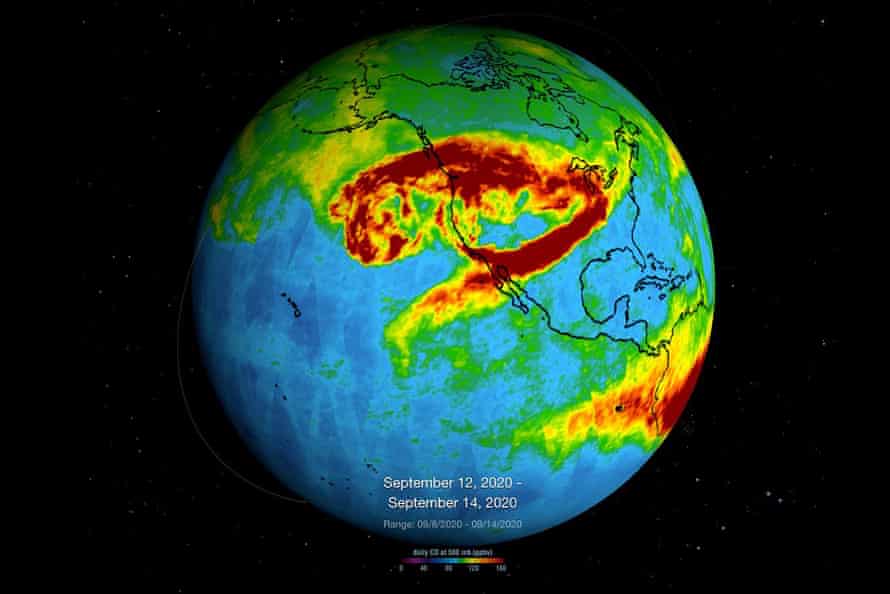

The study, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, combined data from satellite images of smoke plumes with measurements obtained from ground air monitors, which record local air pollution, to model total smoke exposure. The study included all states west of (and including) New Mexico, Colorado, Wyoming, and Montana.

Plumes of smoke can be detected by satellite images as they move across the country. But it’s hard to say if they are low enough to affect ground air quality, so the study created statistical models of how pollution in specific locations after fires have evolved, combining information from of satellites, air monitors and data models.

“Everyone knows that fires produce dirty air – so it’s no surprise,” Burke said. “What we were able to do in this study was to quantify the extent of this contribution. And we’ve found that this reverses much of the progress made across the country in improving air quality.

Surprisingly, the study found that smoke from wildfires extends the effects of air pollution to whiter, richer populations. Historically, low-income communities have been hit hardest by air pollution, often because their homes are closest to highways and factories. But the smoke spreads pollutants over much larger areas. Burke said the western United States, where the most wildfires occur, also tends to be whiter and richer than other parts of the country.

As the plumes travel across the country, the pollutants can harm even people living far from fires, in the Midwest or East.

“Smoke from forest fires is a burden that is shared much more evenly than other pollution,” said Burke.

However, other research has shown that low-income populations may be hit harder when smoke covers an area because their smaller, older homes offer them less protection.

Ironically, one of the future solutions to all this smoke could be to start more fires.

The increase in forest fires is in part due to warmer temperatures and drier conditions, but there is a growing consensus that it is also the result of the national fire suppression policy, instead of the occasional let burn the land.

“There’s a huge amount of fuel on the ground,” Burke said. “Climate change dries it up and makes it much more flammable.”

Burke said a policy of using prescribed burns, which involves starting carefully controlled fires to remove some of the brush, could be a major strategy to curb forest fires and reduce dangerous smoke exposures in coming years.

“The benefits can be quite significant, but there are a number of key issues that need to be explored,” he said.

Otherwise, “under the status quo years like 2020, which were historically out of the ordinary, could become much more the norm,” he said. “It’s a little terrible to think about.”

[ad_2]

Source link