[ad_1]

A team of microbiologists studying glacial ice in Tibet found 33 different viruses dating from the Pleistocene in the carrots they collected. They suspect that viral communities may have been active on the surface of glaciers before they were frozen, and that some may be active even inside ice cores.

Viruses found in the ice cap, called Guliya, are believed to have infected microbes that inhabited the same ice. The team does not know when these infections occurred, however, whether the viruses were most active before the ice sheet formed or only developed after they did. Their comprehensive analysis of the ecology of viruses was recently published in the journal Microbiome.

Based on the genetics of the different viruses, the team was able to assign different bacterial hosts to some of them. The team notes that climate change means these pathogens are disappearing from their stasis in glaciers, which could be a problem in several ways. “Such a merger will not only result in the loss of these old archived microbes and viruses, but will also release them into the environment in the future,” according to the new document.

The team’s cores were wrapped in plastic and placed in cardboard cases covered with foil. They were then shipped out of the ice cap in freezers on a truck, then a plane, then another plane, then a truck again, and are now stored at the Byrd Polar and Climate Research Center at Ohio State University in a cool place – 30 degrees Celsius (-22 degrees Fahrenheit). These hearts and the viruses they contain probably pose no threat to us. “The way we work with these cores, [the viruses] are immediately “killed” by the chemistry of nucleic acid extraction, so the viruses are not active, “said co-author Matthew Sullivan, Ohio State microbiologist and director of the Center for Microbiome Science of university, in an email.

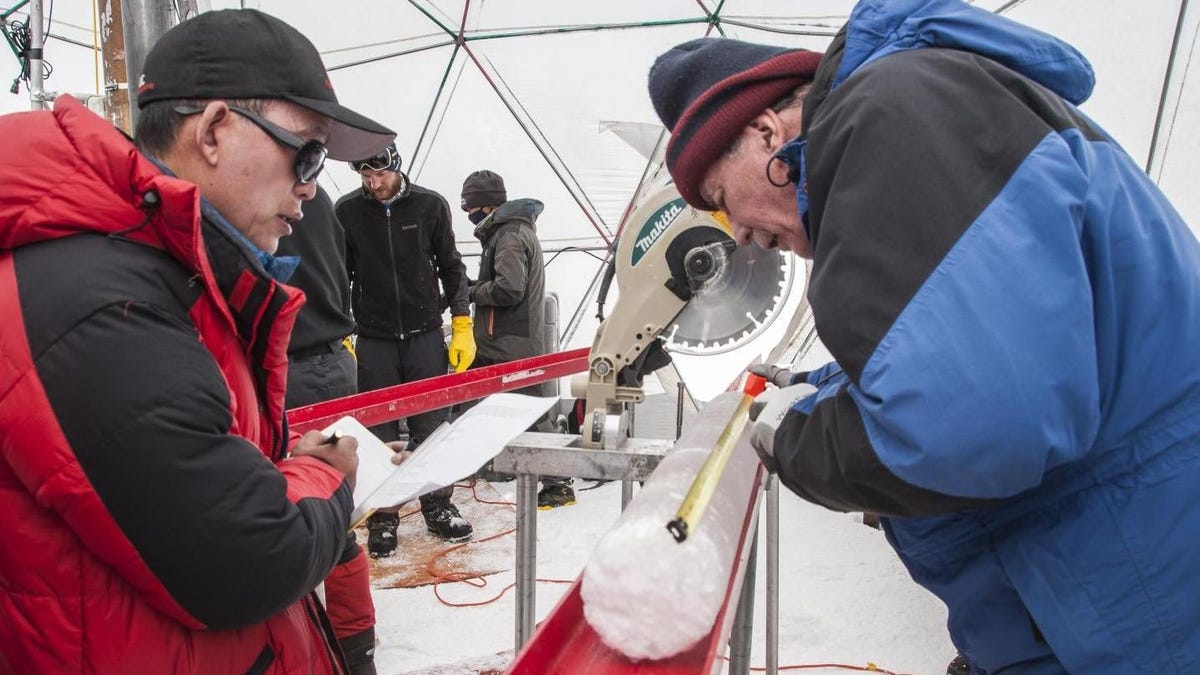

Of the 33 viruses identified in the ice, 28 were new, meaning they had not been previously documented by science. Frozen viruses came from families that commonly infect bacteria. The team identified the viral elements after decontaminating the ice in a multi-step process: After scraping the surfaces of the ice cores in a lab environment with a sterilized saw, they washed the carrots in water. ethanol and water and bathed them in ultraviolet light. Then the carrots were filtered, concentrated and sampled for genetic material. The detected genetic material was then compared to sets of virus genes in a widely used database.

G / O Media may earn a commission

About half of the viruses had genetic signatures indicating they were built for the Ice Ages. “These are viruses that would have thrived in extreme environments,” Sullivan said in a Press release. “These viruses have gene signatures that help them infect cells in cold environments – just surreal genetic signatures for how a virus is able to survive in extreme conditions.”

“These glaciers formed gradually, and along with the dust and gas, many viruses also settled in this ice,” said Zhi-Ping Zhong, lead author of the study and researcher at Ohio State University Byrd Polar and Climate Research. Center, in the same version. “Glaciers in western China are not well studied and our goal is to use this information to reflect past environments. And viruses are one of those environments.

On the one hand, there is a non-zero chance that melting glaciers will release active viruses into the world not seen since the Pleistocene. On the other hand, as reported by Vice, frozen biomass is often in such small quantities that it is the outside world that threatens it, not the other way around.

Based on the amount of genetic evidence the team found in the carrots, the researchers suggest that the resident viruses may still be active in the glacier. It’s also possible that so much viral material ended up in the ice that enough was left for extraction and sequencing thousands of years later.

More: What a 30,000-Year-Old Giant Zombie Virus Means for the Future

[ad_2]

Source link