[ad_1]

THE BIGGEST fear of most health workers battling the Ebola virus is to contract the deadly virus, which forces people to run blood through all the orifices. But for Dr. Richard Valery Mouzoko Kiboung, a Cameroonian epidemiologist working for the World Health Organization (WHO), violence was also a pressing concern. Dr. Mouzoko was based in Butembo, a town in the eastern Democratic Republic of Congo and the center of an Ebola outbreak that was detected nine months ago. The surrounding area is actually a war zone, home to more than 100 militias. Locals are misunderstanding and suspicious of health workers.

On April 19, gunmen took part in a meeting of the local Ebola response team that he was leading. The attackers took everyone's phone and started firing. Two people were injured. Dr. Mouzoko was killed. A few hours later, a group of people armed with machetes attempted to set fire to an Ebola treatment center in a hospital in the nearby town of Katwa.

Violence is part of a trend. In February and March, several clinics were attacked, forcing Médecins Sans Frontières, a charitable organization in the field of medicine, to fire its staff around Butembo. A car carrying WHO experts was ambushed and damaged by men armed with sticks. Assailants armed with machetes have ransacked the head of a health worker responsible for safely burying the victims of Ebola, so that their corpses do not infect new victims. Congo "is an environment as complex and volatile as I have seen it," says Mike Ryan, who heads WHO's health emergency program.

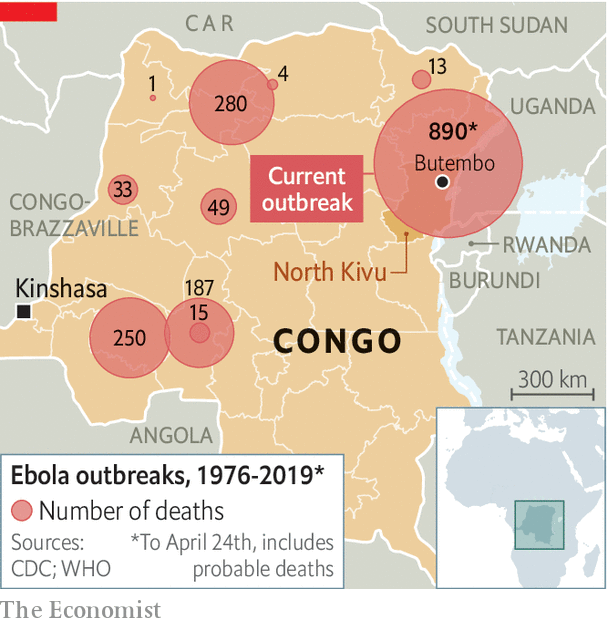

WHO and other stakeholders appeared to be in control of the epidemic in January, but the violence delayed their efforts. The virus infected nearly 1,400 people and killed nearly 900. In April, the WHO said the risk of spreading the Ebola virus was very high, including in neighboring countries like Uganda, Rwanda and Burundi. These countries were invited to start vaccinating health workers and to monitor the virus. The WHO says that much remains to be done to map the movement of people, such as workers and refugees, across borders.

Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, WHO chief, says it is becoming difficult to persuade his staff to go to the field. He goes to Butembo to try to calm his workers and analyze the situation. He is now expecting an increase in the number of Ebola cases. "Whenever there is an attack, the response is slowed down and the number of cases increases immediately as the virus takes advantage and continues unabated," he says.

Locals, whose basic needs have long been neglected, are hostile to the massive deployment of resources simply to fight the virus. Past efforts by police and armed forces to force the population to take preventive measures have alienated the local population. Some even imagine that the government is using Ebola to exterminate the Nandes, the largest ethnic group in the region, or that the emergency situation was designed to prevent people from voting in the elections of last year. The idea that Ebola does not really exist has been spread by some groups for political gain, says Dr. Tedros, who described the phenomenon as "playing with fire". He added that local leaders had agreed to convey the same message about the dangers of Ebola.

The WHO has so far refused to declare the epidemic a public health emergency of international concern, its most alarming. The means of fighting the Ebola virus are well understood from previous epidemics. These include the quick and safe burial of victims, the search for contacts of infected persons and the vaccination of people in the affected areas. Dr. Tedros said he agreed to increase immunization coverage as soon as possible. There is also talk of using a different type of vaccine that could be administered to a greater number of people than currently used. But it is almost impossible to do all this unless health workers can be kept safe.

[ad_2]

Source link