[ad_1]

Press release

Monday, June 10, 2019

The results of studies involving primates suggest that speech and music have been able to shape the auditory circuits of the human brain.

In the eternal quest to understand what makes us human beings, scientists have discovered that our brains are more sensitive to the pitch, the harmonic sounds we hear when we listen to music, than our evolving parent, the Macaque Monkey. . The study, funded in part by the National Institutes of Health, highlights the promises of Sound Health, a joint NIH / John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts project that aims to understand the role of healthy music.

"We found that a certain region of our brain had a stronger preference for sounds with a height than that of the macaque monkey," said Bevil Conway, Ph.D., researcher of the NIH's Intramural Research Program. and lead author of the study published in Nature. Neuroscience. "The results raise the possibility that these sounds, which are embedded in speech and music, may have shaped the fundamental organization of the human brain."

The study began with a friendly bet between Dr. Conway and Sam Norman-Haignere, Ph.D., postdoctoral fellow of the Zuckerman Institute for Mind, Brain and Behavior at Columbia University, and first author of the article.

At the time, both worked at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). Dr. Conway's team was looking for differences between the way the human and monkey brains control vision, to discover that there are very few of them. Their studies of brain mapping suggested that humans and apes see the world in a very similar way. But then, Dr. Conway heard about some of the hearing studies done by Dr. Norman-Haignere, then a postdoctoral fellow in the lab of Josh H. McDermott, Ph.D., associate professor at MIT.

"I told Bevil that we had a method to reliably identify a region of the human brain that selectively responds to sounds with pitch," said Dr. Norman-Haignere. It was at that time that they had the idea of comparing humans with apes. Based on his studies, Dr. Conway bet they would see no difference.

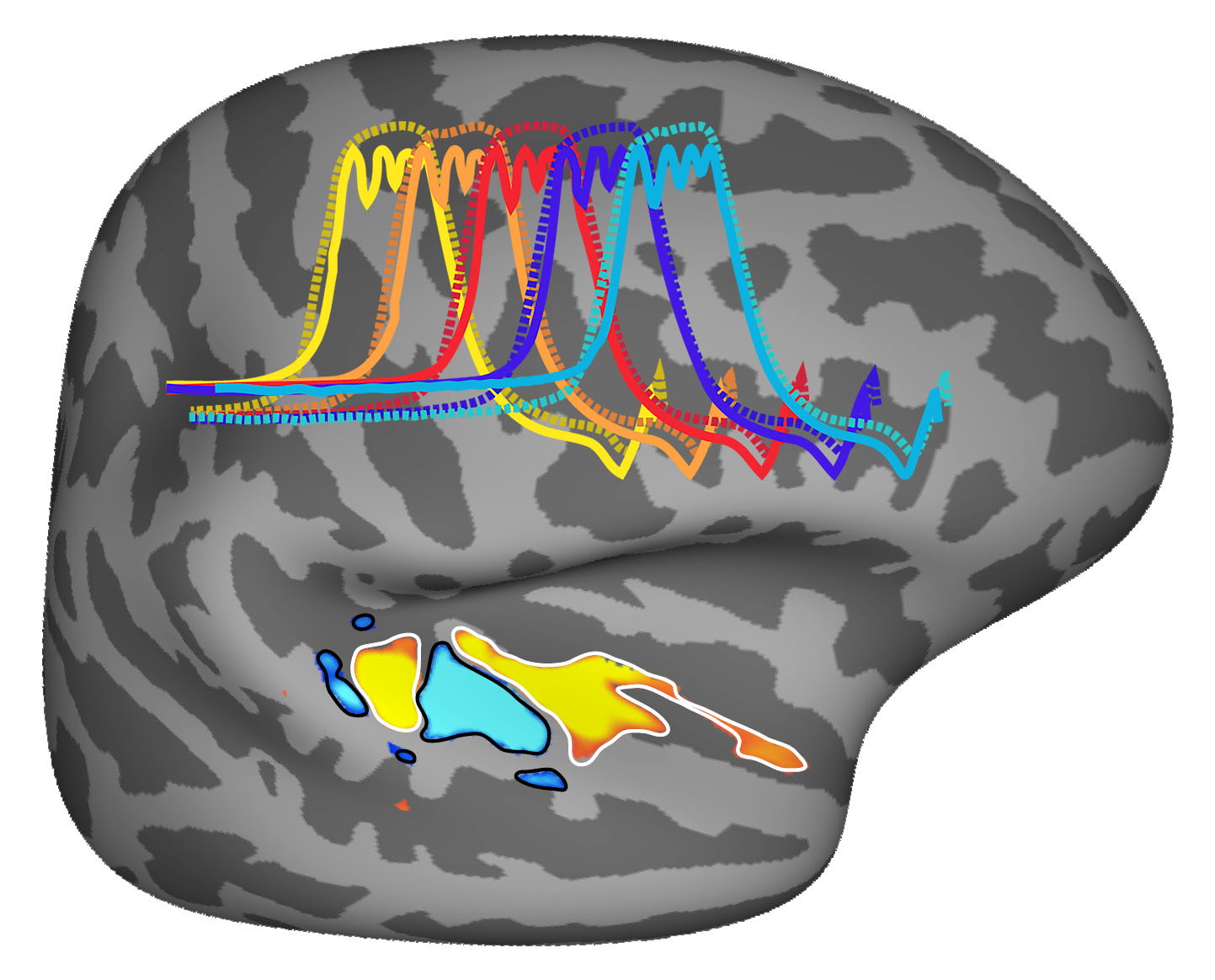

To test this, the researchers played a series of harmonic sounds, or tones, to healthy volunteers and monkeys. At the same time, functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) has been used to monitor brain activity in response to sounds. The researchers also monitored cerebral activity in response to noise-free noises designed to match the frequency levels of each sound played.

At first glance, the scans seemed similar and confirmed previous studies. The auditory cortex maps of the human brain and monkey brain had similar activity hotspots, whether the sounds contained sounds or not.

However, when the researchers took a closer look at the data, they found evidence suggesting that the human brain was very sensitive to tones. The human auditory cortex was much more sensitive than the monkey cortex when it examined the relative activity between sounds and noisy equivalent sounds.

"We found that the brains of humans and monkeys had very similar responses to sounds in all frequency ranges. It was when we added a tonal structure to the sounds that some of these areas of the human brain became more responsive, "said Dr. Conway. "These results suggest that the macaque monkey could experience music and other sounds differently. On the other hand, the macaque's experience in the visual world is probably very similar to ours. One wonders what kind of sounds our evolutionary ancestors have experienced. "

Other experiences have corroborated these results. Slightly increasing the volume of tonal sounds has little effect on the sensitivity of the tone observed in the brain of two monkeys.

Finally, researchers found similar results when they used sounds containing more natural harmonies for monkeys by playing macaque call records. The brain analyzes showed that the human auditory cortex was much more sensitive than the monkey cortex when it compared the relative activity between the calls and the noiseless and noisy versions of the calls.

"This discovery suggests that speech and music may have fundamentally changed the way our brains treat sounds," said Dr. Conway. "It can also help explain why it has been so difficult for scientists to train monkeys to perform auditory tasks that humans find relatively little effort."

Earlier this year, other US scientists applied for the first round of research grants from NIH Sound Health. Some of these grants could eventually help scientists who are exploring how music activates the auditory cortex circuits that make our brain sensitive to musical tone.

This study was funded by the NINDS, NEI, NIMH and NIA intramural research programs and by the NIH (EY13455; EY023322; EB015896; RR021110), the National Science Foundation (grant 1353571; CCF-1231216), the McDonnell Foundation Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

This study was funded by the NINDS, NEI, NIMH and NIA intramural research programs and by the NIH (EY13455; EY023322; EB015896; RR021110), the National Science Foundation (grant 1353571; CCF-1231216), the McDonnell Foundation Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

NINDS is the main funder of research on the brain and the nervous system. NINDS 'mission is to research fundamental knowledge about the brain and the nervous system and to use it to reduce the burden of neurological diseases.

About the National Eye Institute (NEI): NEI directs federal government research on the visual system and eye diseases. NEI supports basic and clinical science programs aimed at developing eye-saving treatments and meeting the special needs of the visually impaired. For more information, visit https://www.nei.nih.gov.

About the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH): The mission of NIMH is to transform the understanding and treatment of mental illness through fundamental and clinical research, paving the way for prevention, recovery and healing. For more information, visit the NIMH website.

About the National Institutes of Health (NIH):

The NIH, the country's medical research agency, has 27 institutes and centers and is part of the US Department of Health and Human Services. NIH is the lead federal agency that leads and supports basic, clinical and translational medical research. She studies causes, treatments and cures for common and rare diseases. For more information on NIH and its programs, visit www.nih.gov.

NIH … transforming discovery into health®

article

Norman-Haignere et al., FMRI responses to harmonic sounds and noises reveal a divergence in the functional organization of the human and macaque auditory cortex. Nature Neuroscience, June 10, 2019 DOI: 10.1038 / s41593-019-0410-7

[ad_2]

Source link