[ad_1]

Reconstruction of Mollisonia plenovenatrix, by Joanna Liang. Mollisonia was only about 2.5 cm long. Credit: Illustration by Joanna Liang © Royal Ontario Museum

Two palaeontologists working on the world-famous Burgess Shale have revealed a new species called Mollisonia plenovenatrix, which is now considered the oldest chelicere. This discovery places the origin of this vast group of animals – more than 115,000 species, including crabs, scorpions and spiders – more than 500 million years ago. The results were published in the prestigious journal Nature September 11, 2019.

Mollisonia plenovenatrix would have been a ferocious predator – for his size. As big as a thumb, the creature boasted of a pair of large, egg-shaped eyes and a "multi-tool head" with long legs that work, as well as many pairs of members who can feel, grab, crush and chew at the same time. But, more importantly, the new species also had a pair of tiny "claws" in front of her mouth, called chelicerae. These types of appendages, which are primarily used to maintain and kill prey, are found only in chelicerates, a major group of arthropods including modern scorpions and spiders.

"Prior to this discovery, we could not identify chelicerae in other Cambrian fossils, although some clearly show similar characteristics to those of chelicerat," says lead author Cédric Aria, a Burgess Shale expedition member. of the Royal Ontario Museum since 2012. currently a postdoctoral fellow at the Institute of Geology and Paleontology of Nanjing (China). "This key element, this blazon of chelicerates, was always missing."

Other features of this fossil, notably the hind limbs assimilated to the gills, suggest further that Mollisonia was not a "primitive" version of a chelicerate, but was in fact already morphologically close to modern species.

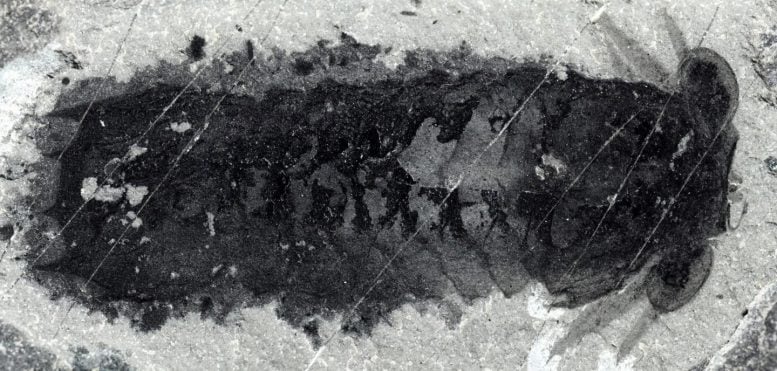

Mollisonia plenovenatrix preserved in dorsal view, showing large eyes, moving legs and small cheliceres at the front. Credit: Jean-Bernard Caron © Royal Ontario Museum

"Chelicerates have what we call gills or lungs for books," says Aria. "Their respiratory organs are made up of many thin sheets assembled like a book. This greatly increases the surface area and therefore the efficiency of gas exchange. Mollisonia had appendages made with the equivalent of only three of these leaves, which probably evolved from simpler limbs. "

The authors believe that Mollisonia hunted preferentially near the seabed, thanks to its well-developed walking legs, a kind of ecology called benthic predation. Mollisonia "Modern" features indicated that chelicerates appeared to have thrived rapidly, occupying an ecological niche that was otherwise poorly exploited by other arthropods at that time. The authors conclude that the origin of chelicerates must lie even deeper in the Cambrian, when the heart of "the explosion" actually took place.

"The evidence converges to indicate that the Cambrian explosion is even faster than we originally thought," said Aria. "Finding a fossil site like Burgess shale in the early days of the Cambrian would be like looking in the eyes of the cyclone."

The importance of Burgess Shale and similar deposits, such as Chengjiang Biota in China, lies in the exceptional preservation of the first marine animal communities in an era of extremely rapid body-shape diversification called the Cambrian Explosion. The sites are remarkable for the preservation of a wide range of morphological features, such as limbs and eyes, but also the intestines and, much more rarely, the tissues of the nervous system.

Mollisonia was first described more than a century ago by the discoverer of the Burgess Shale, Charles Doolittle Walcott. However, until now, only rare exoskeletons of this animal were known. "This is the first time that evidence of limbs and other soft tissues of this type of animal has been described, which has revealed its affinity," says co-author Jean-Bernard Caron, Richard M. Ivey, Curator of Invertebrate Paleontology. at the Royal Museum of Ontario (Canada). Exceptionally well-preserved fossils come from a new Burgess shale site near Marble Canyon in Kootenay National Park, British Columbia.

"Marble Canyon is the biggest projector of my career to date. Every year, this region offers us wonderful treasures, "says Caron, who has been directing the Burgess shale expeditions to the Royal Ontario Museum for the past 10 years. "I would not have imagined that we could, somehow, rediscover the Burgess Shale like this one hundred years later, with all the new species we find."

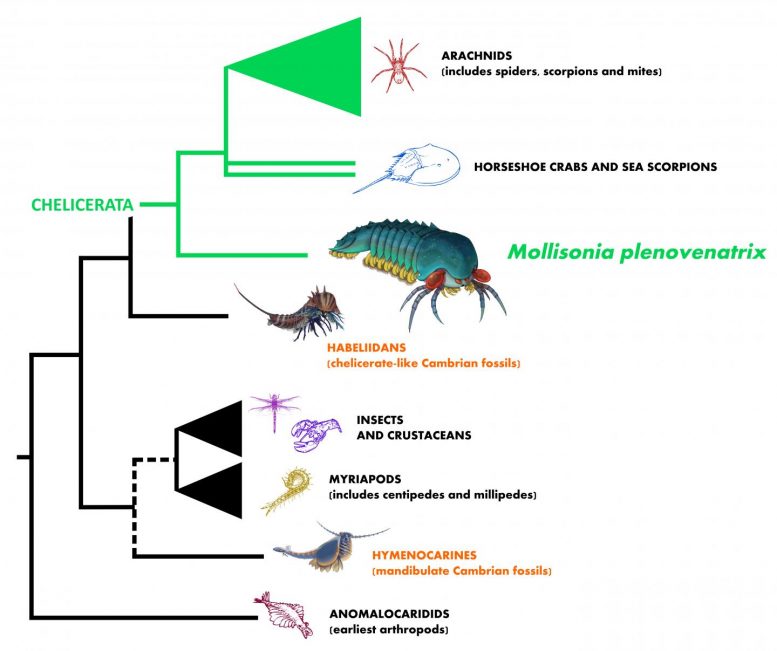

Evolutionary tree illustrating the relationship of Mollisonia with other arthropods. This study places it as a base in chelicerates, a group consisting of arachnids (scorpions, spiders, mites and their relatives), horseshoe crabs and sea scorpions. Some Cambrian (orange) fossils have recently played an important role in understanding the origin of arthropod groups, mandibles and modern chelicera. Credit: Cédric Aria © Royal Museum of Ontario

The specimens of Mollisonia plenovenatrix The works described in this new study are better preserved than those found in Walcott's original quarry, located about 40 kilometers northwest of the Marble Canyon quarry. Many other fossils found in Marble Canyon and in the surrounding areas have already played a vital role in our understanding of the early evolution of many animal groups. These include vertebrates, our own lineage, thanks to many exceptionally well preserved specimens of primitive fish. Metaspriggina walcotti. Many new species are waiting to be described. the last, a new predatory arthropod "resembling a flying saucer" with huge rake-like claws called Cambroraster falcatus, has just been released on July 31, 2019.

The Burgess Shale fossils are located in Yoho and Kootenay National Parks and are managed by Parks Canada. Parks Canada is proud to work with leading scientists to deepen our knowledge and understanding of this key period in the history of the Earth and to share these sites with the world through award-winning guided tours. The Burgess Shale was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1980 because of its Outstanding Universal Value and is now part of the larger World Heritage Site of the Canadian Rocky Mountain Parks.

Mollisonia will be among the many outstanding fossils of the Burgess Shale that are expected to be on display in the future ROM Gallery, the Willner Madge Gallery, Dawn of Life, scheduled to open in 2021.

###

The Royal Ontario Museum (research and collection grants, natural history research grants), the Polk Milstein family, the National Geographic Society (JBC No. 9475-14), the Swedish Research Council ( Michael Streng), National Science Foundation (NSF-EAR-1554897) and Pomona College (Robert R. Gaines). The research was also funded by NSERC's Caron Discovery Grant (# 341944) and the Dorothy Strelsin Foundation (ROM). Aria's Research at the Nanjing Institute of Geology and Paleontology is supported by a grant from the President's International Research Initiative (# 2018PC0043) and a grant from the Foundation for Postdoctoral Science in China (# 2018M630616) .

Reference: "An arthropod of the Middle Cambrian with cheliceres and gills of proto-books" by Cédric Aria and Jean-Bernard Caron, September 11, 2019, Nature.

DOI: 10.1038 / s41586-019-1525-4

[ad_2]

Source link