[ad_1]

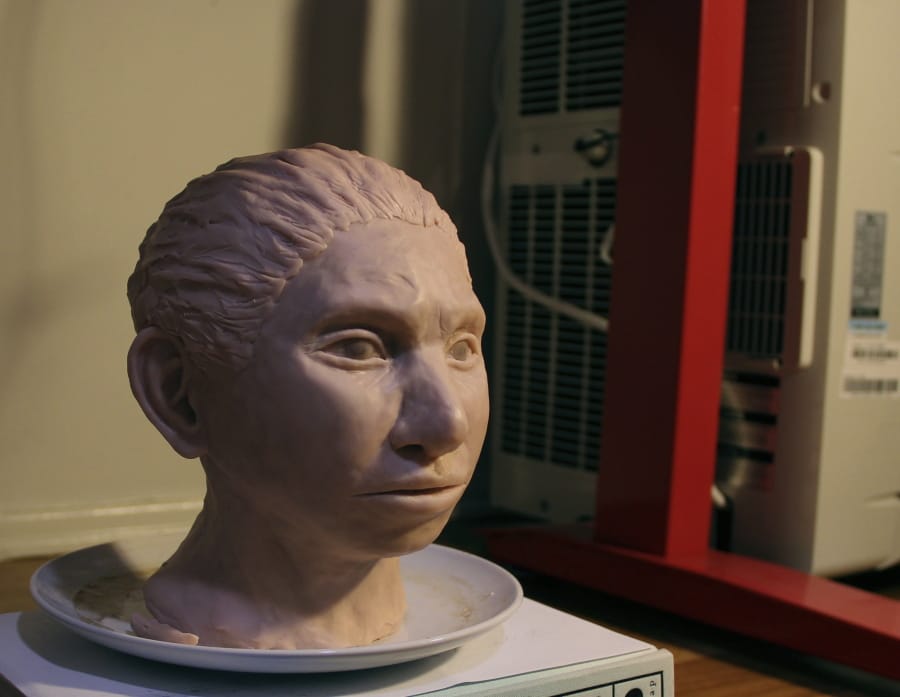

NEW YORK – Scientists say they have deciphered the features of the skull and some other details of a mysterious cousin and extinguished Neanderthals by analyzing its DNA.

The genetic material comes from the finger bone of a member of Denisovans, a population known mainly for its bone fragments and teeth found in the cave of Denisova, Siberia.

The Denisovans may have occupied this cave from more than 200,000 years ago to around 50,000 years ago. Recently, a jaw fragment of Denisovan, at least 16,000 years old, has been reported in China. But it still gave scientists very few traces of what Denisovans looked like.

Modern humans do not come from Denisovans or Neanderthals, although our species has crossed with both and has picked up genetic markers that are still detectable in some populations.

The new work used DNA data from two Neanderthals, five old and 55 current members of our own species, and five chimpanzees, in addition to Denisovan's bone. The findings were reported Thursday in the journal Cell by Liran Carmel of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and others.

They looked for differences in the levels of specific gene activity that could affect anatomical features, which suggested some differences in appearance for these traits. They identified 32 traits that gave clues to Denisovan's skeleton.

As expected, most were shared with Neanderthals, including stout jaws, a low forehead, a large rib cage and a large pelvis.

The analysis also indicated that the Denisovans had a broader face than Neanderthals and our own species, and a more prominent face than our own species but less than Neanderthals, for example. The calculations could not tell what the magnitude of these differences was.

Such an analysis of DNA can teach scientists how our predecessors have evolved and how their development has differed, Carmel said in an email.

The method showed good precision in predicting the known physical characteristics of Neanderthals and chimpanzees, the researchers said. Carmel said that the Denisovan jaw fossil corresponded to the "almost perfectly" method.

Experts not connected to work were impressed.

Although it is impossible to know how accurately the study estimates Denisovan's features, his approach is "brilliant and original," said Benedikt Hallgrimsson of the University of Calgary.

Once the proper fossils have been found, the study's specific predictions can be tested, said Hallgrimsson, who is studying the evolutionary aspects of the influence of genes on the physical characteristics of mammals.

Bence Viola of the University of Toronto, who studies Denisovan's fossils, described the work as "a big step forward … It would have been called science fiction five years ago."

The general picture of anatomy is "inestimable", although some details are probably inaccurate, he said.

Viola said he was skeptical about rendering an artist who would have added skin, eyes and hair to the skull produced by the study. Scientists do not know enough Denisovans to ensure the accuracy of these reports, he said.

Carmel, who commissioned the renderings, stated that they were as anatomically accurate as possible, but that they "necessarily represented certain artistic interpretations."

[ad_2]

Source link