[ad_1]

Deep sea animals can be the subject of nightmares.

Many inhabit the twilight zone of the ocean (up to 1000 meters deep), where sunlight has all but disappeared, and have adapted their vision to this dark alien world. Evolution has given them large, complex eyes to see in the dim light – examples include the vampire squid, Sloane’s viper fish, and various predatory crustaceans.

But how far back in prehistoric times do these frightening and piercing-eyed creatures go?

Our study, published today in Science Advances, looked at radiodonts (meaning “radiating teeth”) – an ancient type of arthropod (animals with jointed legs but no spine).

We discovered that they had developed sophisticated eyes over 500 million years ago, and some were adapted to the dim light of deep waters.

Our study provides new information on the evolution of the first ecosystems of marine animals.

In particular, he supports the idea that vision played a crucial role during the Cambrian Explosion, a pivotal phase in history when most major groups of animals (including the older fish) emerged for the first time in a rapid burst of evolution.

Once complex visual systems arose, animals could sense their surroundings better. This may have fueled an evolving arms race between predators and prey. Once established, the vision became a driver of evolution and helped shape the biodiversity and ecological interactions we see today.

Katrina kenny, Author provided

Read more: Life Finds Its Way Quickly: The Evolving Big Bang Ends Surprisingly Quick

A short guide to radio stations

Radiodonts are strange animals. Now extinct, they once ruled the oceans, especially during the Cambrian Period (541 million to 485 million years ago).

Some of the first radiodont fossils discovered over a century ago were isolated body parts, and the first attempts at reconstruction resulted in “Frankenstein monsters.”

But over the past few decades, many new discoveries – including entire radiodont bodies – have provided a clearer picture of their anatomy, diversity, and possible lifestyles. Nevertheless, full radio broadcasts still look like something out of science fiction!

There are many species of radiodonts and they share a similar body disposition.

The head has a pair of large, segmented appendages to capture prey, a circular mouth with jagged teeth, and a pair of eyes. The rest of the body looks more like that of a squid.

It may look like a chimera of different animal parts, but the articulated appendages and compound eyes allow us to classify radiodonts as arthropods, which include insects, spiders, and crabs.

John paterson

Over the past decade, new radiodont fossils have revealed an astonishing variety of forms and improved our understanding of their way of life and especially their diet.

A kind of radio station, Anomalocaris, has long been considered a top predator, similar to the modern great white shark. It had a large body, over two feet long, and very tough spiny appendages to the head which it used to catch prey. He swam, waving flaps on the sides of his body.

However, other radiodonts were gentle giants, such as the two-meter-long genre Aegirocassis, which used its appendages to filter plankton.

Good to see you with

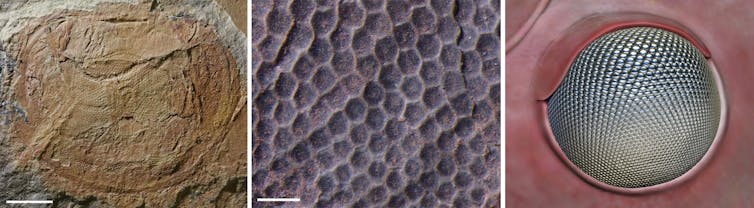

Despite the recent surge in knowledge about these impressive arthropods, little was known about the optics of the radiodont eyes. In 2011, we published two articles in the journal Nature about eyes composed of fossils from the 513 million year old Emu Bay shale on Kangaroo Island, South Australia.

The first article documented isolated ocular specimens (up to 1 cm in diameter) that could not be attributed to a known arthropod species. The second article reported the hunted eyes of Anomalocaris in spectacular detail.

Since then, we have amassed a much larger collection of eyes from the Emu Bay Shale, shedding new light on the vision of radio stations.

Importantly, our new study identifies the eye owner of our first article from 2011: ‘Anomalocaris‘ Briggsi – inverted commas indicate that it represents a new genus that has not yet been officially named.

We have discovered much larger specimens of these eyes (up to 4 cm in diameter). They have a distinctive “sharp zone” – enlarged lenses in the center of the eye’s surface that improve light capture and resolution.

Katrina kenny, Author provided

Radiodont eyes are also extremely sensitive. One eye of Anomalocaris aff. canadensis – “aff.” meaning “affinity” because it is closely related to this Canadian species – with over 24,000 lentils, only matched by certain insects like dragonflies. These make it a very visual predator, in shallow water, capturing prey with appendages bearing barbed spines.

The large lenses of ‘Anomalocaris‘ Briggsi suggest he could see in a very shallow light at depth, similar to amphipod crustaceans, a type of shrimp-like creature that exists today. The frilly thorns on its appendages filtered out the plankton it detected looking up.

John paterson

The compound eyes of the two radiodonts of the Emu Bay shales are outliers among arthropods, living or extinct. Their sheer size places them among the largest arthropod eyes ever created.

Read more: Definitive borders: the deep sea

[ad_2]

Source link