[ad_1]

Astronomers were struck Thursday, December 3 by a huge wave of data from the European Space Agency Gaia Space Observatory.

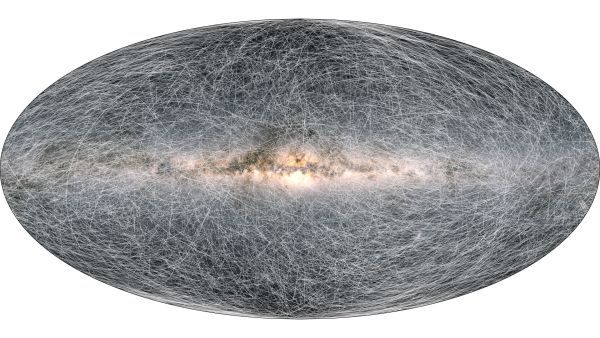

These researchers can now explore the best map of the Milky Way, with detailed information on the positions, distances and motion of 1.8 billion cosmic objects, to help us better understand our place in the universe.

“Gaia’s data is like a tsunami going through astrophysics,” said Martin Barstow, head of the Department of Physics and Astronomy at the University of Leicester, who is part of the Gaia data processing team. . He was speaking at a virtual press conference on Thursday, in which another Gaia researcher, Giorgia Busso of the Leiden Observatory in the Netherlands, also told reporters that the data produced “a revolution “in many areas of astrophysics, from the study of galactic dynamics such as stellar evolution to the study of nearby objects like asteroids in the solar system.

Pictures: The Gaia spacecraft to map the Milky Way galaxy

Gaia was launched in December 2013 to map the galaxy in unprecedented detail. The billion dollar spaceship revolves around the Lagrange-2, or L2, point, a place about 1 million miles (1.5 million kilometers) from Earth, where the gravitational forces between our planet and the sun are balanced and the view of the sky is clear. Gaia can measure around 100,000 stars every minute, or 850 million objects every day, and can scan the entire sky about once every two months.

The latest data mine improves the accuracy and scope of the two previous Gaia datasets, which were released in 2016 and 2018. For example, compared to 2018 data, which included measurements for 1.7 billion objects, 2020 data improves data point accuracy by a factor of two for correct motion, or the apparent change in motion. position of a star seen from our solar system.

“It really gives us a glimpse into the life of the Milky Way,” said Nicholas Walton, an astronomer at the University of Cambridge who is part of Gaia’s science team. scientific and press conference. “We are talking about billions of stars, which really gives us the ability to probe at a significant level the entire population of the Milky Way, as you would like to do when studying people.”

Walton said the cosmic census would be like having trackers on every person in the UK to map their location and monitor their health. “If everyone has a tracker, we could tell you if they are sweating or not. It’s kind of like that with the stars here: we can tell you which ones are sweating, which are active, which are dormant, which will die. , which will explode. “

Gaia’s data has already been used in a wide variety of applications over the past four years. The mission helped researchers find corpse of a galaxy that the Milky Way cannibalized 10 billion years ago, 20 hypervelocity stars unexpectedly zooming in to the galactic center and identify 1000 stars nearby where hypothetical aliens could see signs of life on Earth.

Closer to home, the spacecraft allowed scientists to find previously unknown people asteroids, and its precise data even allowed NASA to make a last minute adjustment on its way for its New Horizons probe in 2018 to successfully pass the frozen Arrokoth rock, the most distant and primitive object in the solar system ever visited by a spacecraft.

So far, some 1,600 studies have been published based on Gaia’s data, Barstow said. More will surely result from new material, now available on the ESA website, and at the end of the briefing for scientists and reporters, Walton said he expected a lot of scientists to think about it already: “I think a lot of astronomers would have left this show to work on the data. . “

Some of Gaia’s new data has already been used to make discoveries. A group of researchers led by scientists from Dresden University of Technology measured the acceleration of our solar system inside the Milky Way, using Gaia’s newly observed 1.6 million quasars as a reference point, which are so far away they appear to be fixed in space, like galactic lighthouses.

The solar system has been measured to be accelerating very slightly, as predicted by theorists, towards the galactic center. Busso said this barely noticeable acceleration only became observable in these newly released Gaia data because “the accuracy of the measurements has increased dramatically.”

These super precise tests of how masses are distributed and accelerated are essential to “probe the limits of fundamental physics,” Gerry Gilmore, University of Cambridge astronomer and Gaia scientist, said at the event. Such measurements could help scientists understand the nature of black matter that we know is hiding throughout the universe.

“Even our own sun is moving so fast that our entire Milky Way would split apart if it wasn’t held by dark matter, and we have no idea what dark matter is,” Gilmore said. “The hope is that by continuing the experiments along the line that we’re doing – and making them more precise and doing them at different scales – we’ll be able to see if there are different types of dark matter. “

The third Gaia dataset was due to be released in 2022, but mission scientists have decided to release preliminary data now so astronomers can use it sooner, with at least two more datasets to be released in the years to come. The spacecraft will operate until at least 2022, but its mission could be extended until 2025.

follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

[ad_2]

Source link