[ad_1]

The latest and deadliest wave of coronavirus has erupted across California, leaving no counties untouched in this massive and diverse state, from dense and bustling subways to sprawling suburbs to vast swathes of rural and farmland.

Yet different parts of the state felt the impact very differently.

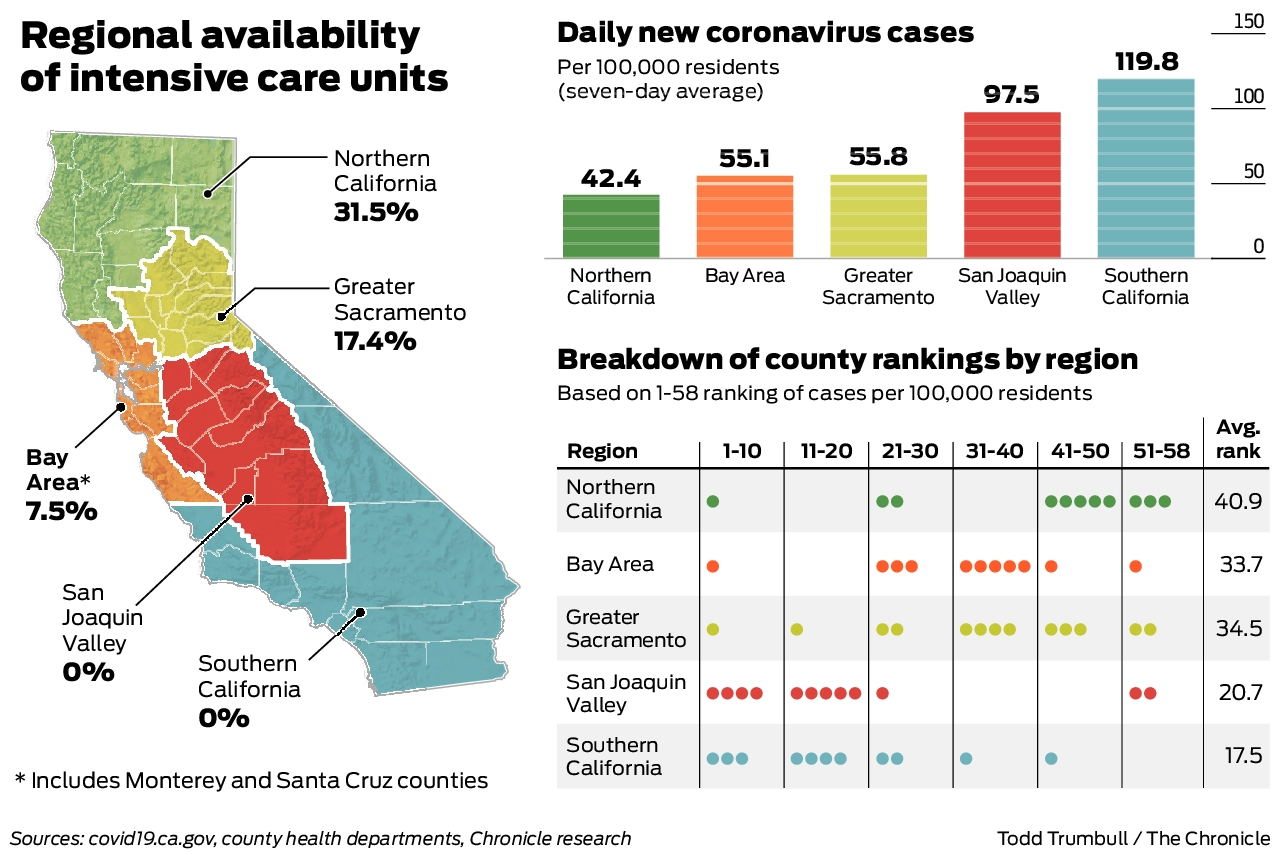

The main stressor of the latest outbreak is the availability of intensive care units. State officials, fearing a post-Thanksgiving spike in cases could overwhelm hospitals, have set a 15% critical care availability threshold to trigger regional lockdown orders. The restrictions are in effect for four of the five regions, comprising more than 98% of the state’s residents.

In northern California, the only region not on stay-at-home orders, nearly one-third of intensive care beds are still available. Greater Sacramento is at 17.4%, and the Bay Area was last reported at 7.5%.

The San Joaquin Valley and Southern California areas are at 0%.

These and other data comparisons highlight the differences between the most populous counties and metropolitan areas of the state, especially between the northern and southern parts of the state.

THE BAY SECTOR

The Bay Area as a whole performs better than some of the more populous areas in and around Los Angeles. The daily rate of new cases per 100,000 people in the Bay Area has ranged from 40s to mid-50s in recent weeks.

“This could reflect the high compliance of the mask, the high ventilation in our area due to its location and the general adherence to the distance in the Bay Area compared to other areas,” said Monica Gandhi, specialist in infectious diseases at UCSF.

She added that a “general confidence of public health officials in the Bay Area, leading to greater compliance with stay-at-home measures” may also explain why the outbreak is not as severe here. than in Southern California.

The case rates differ a bit in the different counties in the Bay Area. San Francisco and Marin counties have lower daily case rates, while Solano, Santa Clara and Napa have seen cases roughly twice as high. But they’re still falling below the state’s daily case rate, which was in the 90s and 100s last week.

Solano County continues to dominate the Bay Area with the highest daily case rates. The county health official attributed the surge to Thanksgiving and other weekend gatherings and activities, and people are still gathering with others or going to work even though they know the risk or are symptomatic.

Santa Clara County has also recently seen high daily case rates – mostly in the mid-1960s per 100,000 population. Dr Ahmad Kamal, the county’s health care preparedness director, said Santa Clara has 28 intensive care beds, or 8.5% uptime, on Wednesday. He said pandemic fatigue was a major driver, and communities of color in the south and east of the county were paying the price.

Kamal said that five days after Christmas, the county has yet to experience a power surge comparable to the one that occurred after Thanksgiving, and he hopes residents have canceled plans and taken extra precautions during the holidays.

“We have major concerns as New Years Eve approaches, which has traditionally been a common time to come together, especially among young people who feel at low risk or less susceptible to the virus,” he said. declared.

Any further increases, Kamal said, “will tip us over the edge” at the point in Southern California, where patients are treated in gift shops and hospital hallways.

“We are wavering on the doorstep and eagerly awaiting what will happen on New Year’s Eve,” he said. “We’re not quite there yet, but we’re really close.”

GREATER SACRAMENTO REGION

Sacramento County’s case rate has recently been near the Bay Area average, going from a bit of the 1960s to the mid-1950s per 100,000 population. At a supervisory board meeting on Wednesday, public health official Dr Olivia Kasirye said before Christmas the county had an average of 800 cases and 10 more deaths per day, and that after the holidays , there were 664 cases and six deaths per day.

“It looks like we are starting to move in the right direction, but it’s still too early to tell,” she said. “We haven’t seen the impact of Christmas and the trips our residents have made during that time, so we’re always very careful about where the numbers are heading.”

While the availability of intensive care in Sacramento County is currently above the state’s 15% lockdown threshold, the health official said the shelter-in-place order may not be lifted anytime soon. if there is a vacation peak, and patients from other busy areas may need to be moved to hospitals in the Sacramento area. Earlier this month, the county began treating some COVID-19 patients at an alternative care facility set up at Sleep Train Arena.

SOUTH CALIFORNIA

Southern California was overwhelmed by the latest outbreak, with cases so rampant that they pushed the state’s rate to No. 1 in the country.

Robert Kim-Farley, professor at the UCLA Fielding School of Public Health, attributes the surge to pandemic fatigue. Southern California counties were also starting from a higher baseline, and many never reached the very low levels the Bay Area counties saw in October.

“With such high levels of disease, the chances of going to the store and coming into contact with the virus are much higher,” he said. “It becomes a snowball effect.”

The composition of Southern California’s workforce has also made the region vulnerable. The counties of San Bernardino and Los Angeles, in particular, have a large number of people working in essential manufacturing jobs. Many are Latinos and live in densely populated, low-income areas where the virus can spread more easily.

According to state data, San Bernardino County has the highest seven-day average case rate in the state at 165.5 per 100,000, the highest positive test rate at 23% and the highest rate of highest positivity among disadvantaged communities at 26.8%.

Los Angeles County also has one of the highest case rates at 132.7 per 100,000, according to state measurements, with a positive test rate of 16.5% and a test positivity rate. health equity of 23.4%. Los Angeles County hospitals have been completely overcrowded, with some ambulances diverting and placing patients in souvenir shops and conference rooms. Authorities fear that if things get worse, hospitals may have to start rationing care.

Los Angeles County has by far the largest population in California, with over 10 million people, and is racially and economically diverse. Experts say the city has been vulnerable since the start of a pandemic. According to the CDC, the county has a high social vulnerability score, which indicates how a natural disaster or disease outbreak can affect the health of a community. Neighboring counties of San Bernardino and Riverside have even higher scores.

Kim-Farley said the sometimes mixed messages from county leaders have confused residents, including those on the divided supervisory board, some of whom want to see the economy reopen and others who want the strong measures of the public health department are continuing.

“People are not united around a common vision and message, and that confuses people,” Kim-Farley said. “This has been a problem at many levels of government.”

In neighboring Orange County, the case rate averaged 104 per 100,000 residents last week. Hospitalizations are up 225% from a month ago. While the stay-at-home order in the Southern California area has been extended, meaning restaurants are closed for in-person dining, some Orange County restaurant owners have defied restrictions by using the hashtag #OpenSafe.

Riverside County recorded 73 deaths on Tuesday, a record high for the county.

The California National Guard has deployed medical staff to support an understaffed county hospital, and overwhelmed patients waiting for beds to open have been placed in the facility’s cafeteria.

Kim-Farley said Southern California counties are having their “New York moment.” As the pandemic began, case rates in New York City skyrocketed and hospitals were overwhelmed.

“I think we’re going to see another increase over the next couple of weeks because of the amplification that happens over the holidays,” he said. “There is a light at the end of the tunnel with vaccines, but the tunnel looks more and more ugly to go through.

Todd Trumbull designed the graphics for this article.

Kellie Hwang is a writer for the San Francisco Chronicle. Email: [email protected]

[ad_2]

Source link