[ad_1]

A recent study of the Greenland ice cap found that glaciers are retreating in almost all areas of the island, while also undergoing other physical changes. Some of these changes lead to the diversion of freshwater rivers under the ice.

In a study conducted by Twila Moon of the National Snow and Ice Data Center, researchers examined in detail the physical changes of 225 of Greenland’s glaciers that terminate the ocean – narrow fingers of ice flowing from the inside of the cap. glacial towards the ocean. They found that none of these glaciers had advanced significantly since 2000 and that 200 of them had retreated.

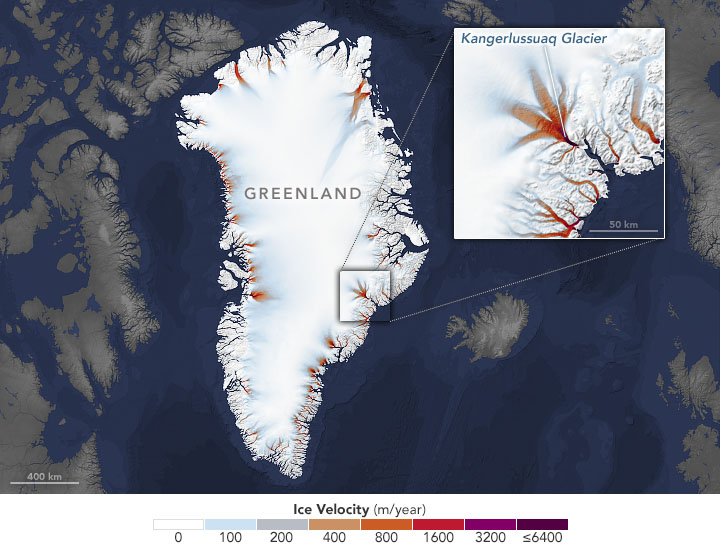

The map at the top of this page shows measurements of ice speed across Greenland as measured by satellites. The data was compiled as part of the Inter-mission Time Series of Land Ice Velocity and Elevation (ITS_LIVE) project, which brings together glacier observations collected by multiple Landsat satellites between 1985 and 2015 into a single dataset open to scientists and to the public.

About 80 percent of Greenland is covered by an ice cap, also known as a continental glacier, which reaches a thickness of up to 3 kilometers (2 miles). As glaciers flow out to sea, they are usually replenished by new snowfall inside the ice cap which compacts into ice. Many studies have shown that the balance between melting glaciers and replenishment is changing, as is the calving rate of icebergs. Due to rising air and ocean temperatures, the ice sheet is losing its mass at an accelerated rate and additional meltwater is flowing into the sea.

“Greenland’s coastal environment is undergoing a major transformation,” said Alex Gardner, snow and ice specialist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory and co-author of the study. “We’re already seeing new sections of the ocean and fjords opening up as the ice sheet recedes, and now we have evidence of changes in these freshwater flows. So losing ice isn’t just about changing sea level, it’s also about reshaping Greenland’s coastline and changing coastal ecology.

While Moon, Gardner and colleagues’ findings are consistent with other observations from Greenland, the new investigation captures a trend that was not apparent in previous work. As glaciers retreat, they also change so as to likely divert freshwater flows under the ice. For example, glaciers change thickness not only as warmer air melts ice from their surfaces, but also as their flow velocity changes. Both scenarios can lead to changes in the pressure distribution under the ice. This, in turn, can change the path of subglacial rivers, as water will always take the path of least resistance (lowest pressure).

Citing previous studies on the ecology of Greenland, the authors note that freshwater rivers beneath the ice cap provide nutrients to bays, deltas and fjords around Greenland. In addition, rivers under ice enter the ocean where ice and bedrock meet, often well below the ocean surface. The relatively floating freshwater rises, carrying the nutrient-rich deep water to the surface, where the nutrients can be consumed by phytoplankton. Research has shown that glacial meltwater rivers directly affect the productivity of phytoplankton, which serves as the foundation of the marine food chain. Combined with the opening of new fjords and sections of ocean as glaciers and ice shelves retreat, these changes amount to a transformation of the local environment.

“The rate of ice loss in Greenland is astounding,” Moon said. “As the ice cap edge responds to rapid ice loss, the character and behavior of the system as a whole changes, with the potential to influence ecosystems and the people who depend on them.

Image from NASA’s Earth Observatory by Joshua Stevens, using Landsat data from the US Geological Survey and NASA / JPL’s Time Series of Land Ice Velocity and Elevation (ITS_LIVE) Inter-mission project -Caltech, and the General Bathymetric Chart of the Oceans (GEBCO). Story of Calla Cofield, Jet Propulsion Laboratory, with Mike Carlowicz.

[ad_2]

Source link