[ad_1]

A system of storms arriving during the second half of next week has the potential to bring moderate to heavy rain throughout southern California, according to the National Weather Service.

Rainfall rates can be high at times, increasing the possibility of debris flows in recent burn areas, as well as mud and rock slides on mountain roads. Significant snowfall accumulations are possible with the storm, mainly above 5,000 feet.

The biggest storm, the third in a series, is expected to incorporate an atmospheric river. Atmospheric rivers are a concentrated stream of water vapor in the middle and lower levels of the atmosphere. Because they are lower in the atmosphere, they tend to be hotter, even though they are not a pipeline directly to the tropics.

This atmospheric river will come more from the west, said Eric Boldt, meteorologist in charge of coordinating alerts at the Oxnard National Weather Service. “It is not a direct tropical connection, but [has] a higher than normal water content which can lead to moderate and regular rains for many hours. “

An atmospheric river is expected to accompany the most powerful of a series of three storms affecting Southland through the end of the week.

(Paul Duginski / Los Angeles Times)

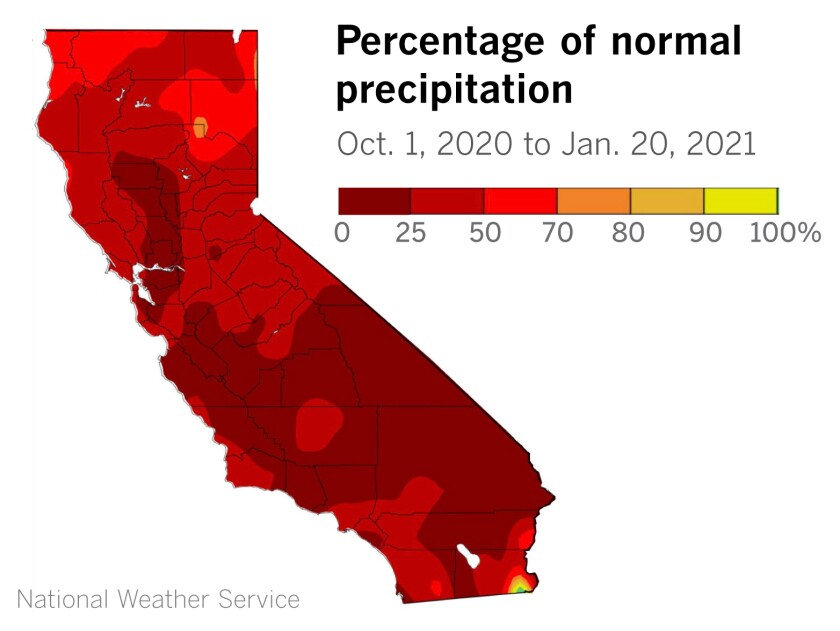

The change in model comes after a record-breaking summer, the worst fire season in California history, and a dry fall and early winter raked by Santa Ana winds.

After a hot summer, the entire state was unusually dry during the fall and early winter.

(Paul Duginski / Los Angeles Times)

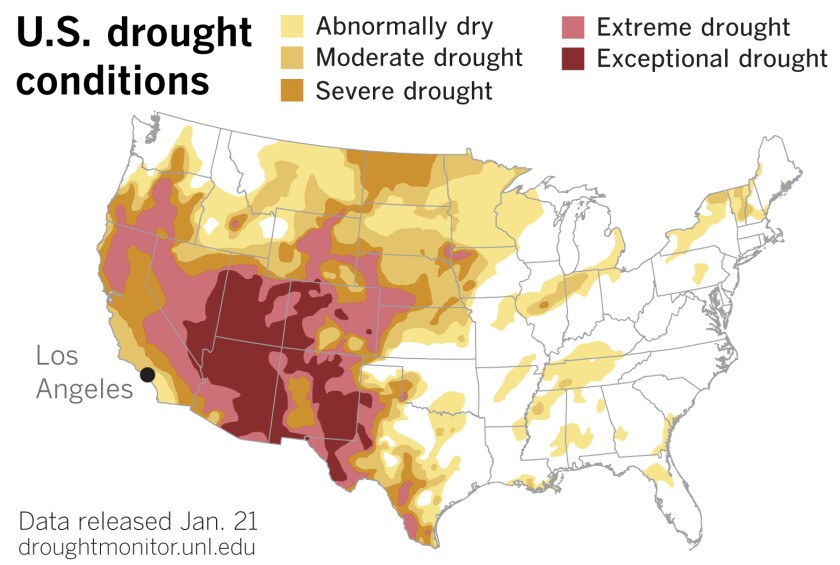

Although the Pacific Northwest and northern Intermountain West have benefited from heavy rainfall following a series of North Pacific storms, the central and southern regions of the West experience roughly drought. as serious as possible. With areas already classified as being in extreme and exceptional drought, “little deterioration can be introduced,” the US Drought Monitor reported Thursday.

A wetter pattern would bring welcome relief in the southwest, which has been parched by prolonged drought. The most recent data from the US Drought Monitor was released on Thursday.

(Paul Duginski / Los Angeles Times)

The only way for such a parched and scorched landscape to get worse would be to release heavy rain from an atmospheric river – rain that looks like a fire hose – washing away mud and debris from the steep slopes. It takes rain, but not all at once. If heavy rains do occur, there is a risk of debris flow in recent burn scars such as those left by the Lake, Bobcat and Ranch2 fires, and other fires in Orange County and the Inland Empire.

Forecasters don’t expect an epic rain scenario, but warn the public should pay attention to updates and follow instructions from authorities if asked to evacuate.

Massive amounts of rain are not necessary to create a dangerous situation. For example, the Montecito Mudslide in Santa Barbara County on January 9, 2018, following the Thomas Fire, occurred after only about a half inch of rain. But that rain fell in about 5 minutes and produced debris flows 15 feet high.

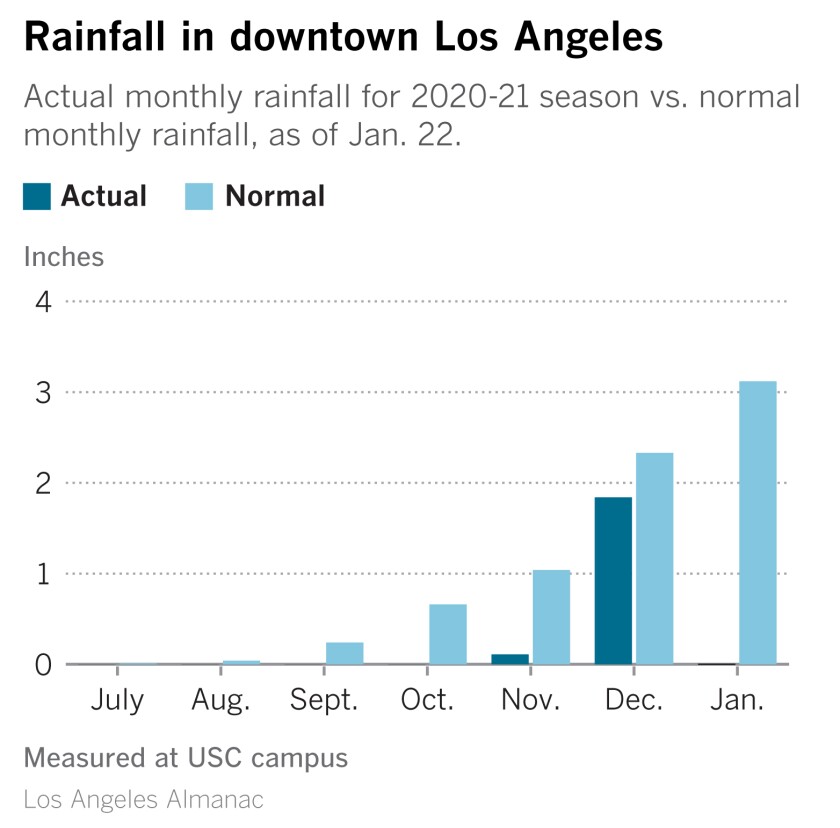

A decent storm in December punctuated an otherwise dry fall and early winter in downtown Los Angeles.

(Paul Duginski / Los Angeles Times)

How did we get to this point?

A La Niña is in place in the equatorial Pacific and is expected to persist through the remainder of the winter. La Niña typically results in a dry winter in Southern California and the southwest, although this is not always the case. El Niño, the wetter cousin of La Niña, usually means a wet winter in Southern California, based on the story, but, again, there are no guarantees.

The Southland has experienced a storm for the past nine months, and the dry regime so far has been consistent with a typical La Niña winter – which is typically characterized by wetter than normal weather in the northwest of the Pacific and across the northern United States.

Even though the Los Angeles area had near normal precipitation last winter, the excessive summer heat and dry Santa Ana winds in the fall and early winter left the fuels dry. Numerous large fires have burned more than 4 million acres in California in 2020, sometimes enveloping almost the entire state in smoke.

In a Mediterranean climate like that of California, rain falls mostly in winter. Even without the influence of El Niño and La Niña, southern California depends on five to seven major storms for its precipitation each year.

“In Los Angeles, it doesn’t rain or drizzle every day during the winter, like in Seattle,” climatologist Bill Patzert said. “The rain comes in five, six or seven events. There are generally less than 20 days of rain and less than 10 days of heavy rain throughout the season. “

The Los Angeles Basin is a floodplain. After a season that began to dry out in 1937-1938, two storms in late February and early March 1938 abruptly brought as much rain over the region in five days as it usually does in an entire season. Catastrophic flooding in the foothills of Long Beach followed, causing the equivalent of a billion dollars in damage in today’s dollars. The Angelenos were fed up with the repetitive, damaging flooding. These events ultimately prompted authorities to tame the Los Angeles River and other waterways by covering them with concrete to fight flooding.

As Patzert points out, these concrete channels do not flow significantly about 99% of the time.

A reminder of what could have happened before these waterways were turned into concrete canals came on New Years Day 1934.

In November 1933, a fire exposed an area of 7.5 square miles in the foothills above Montrose and La Crescenta. Then on December 31, 1933 and January 1, 1934, an atmospheric river storm dropped 10 to 15 inches of rain over communities in the foothills, and up to 20 to 30 inches over the foothills and mountains. Downtown Los Angeles received 8.27 inches of rain, as reported by The Times.

The deadly New Year’s flood made headlines in the Los Angeles Times.

(Los Angeles Times)

“The Montrose Flood, as the calamity was quickly called, left at least 45 dead, destroyed a hundred homes and turned the small community into a barren, mud-filled landscape,” said local historian Art Cobery, who has become an expert on the disaster and its consequences, ”The Times reported in 2009.

After the 1934 New Years flood in Los Angeles, cars were stuck in the mud outside the Bohemian Gardens on Mission Road. A man lost his life there.

(Los Angeles Times)

Singer-songwriter Woody Guthrie commemorated the tragedy in a song about the “Los Angeles New Years Flood”.

Atmospheric rivers are extremely humid plumes of moisture. They can deposit rain on the plains upon reaching land, but as they lift themselves up and traverse steep, rugged hills and coastal mountains, their cargo of moisture is wrung out. This means they deposit heavy rains, perhaps at an intense rate, on the very areas that were stripped of vegetation by forest fires in the previous summer and fall.

“It all serves as an uplifting tale for those who live under scorched areas such as the Bobcat Fire in the San Gabriel Mountains. Landslides cannot be predicted, but they can be anticipated, ”Patzert said. “The best protection against landslides is to stay informed and to evacuate when authorities issue warnings.

“Great droughts, fires, floods and landslides after heavy rains, decade after decade. It’s a story told for thousands of years, ”Patzert added. “It’s a California classic.”

[ad_2]

Source link