[ad_1]

The decline of the Tasmanian devils has an unusual training effect: the animal carcasses have already been swallowed up by the devils, and now it takes several days to disappear.

We made the discovery, published today in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B, placing carcasses in various places and observing what happened. We found that the reduction of cleaning by devils resulted in extra feeding for less efficient collectors, such as feral cats.

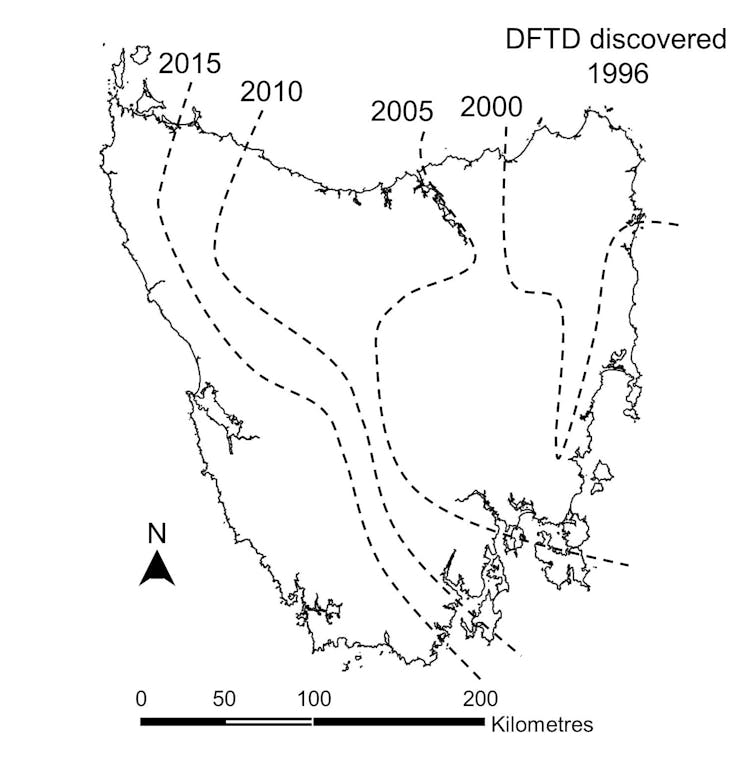

Tasmanian devils have struggled for two decades against a transmissible cancer typically fatal, the disease of the tumors of the face to the devil. The disease has caused devil populations to fall by about 80% on average and up to 95% in some areas.

Calum Cunningham / Menna Jones

Scavengers are carnivores that feed on dead animals (carrion). Almost all carnivores recover to a greater or lesser degree, but the devil is the predominant predator in Tasmania. Since the extinction of the Tasmanian tiger, it is also the largest predator of the island.

A scanning experience

In our study, we set up Tasmanian Pademelon carcasses (a small wallaby weighing about 5 kg) in various locations, ranging from disease-free areas with a large population of demons to areas of long-term disease where the number of demons is very weak. We then used motion-sensing cameras to record all the scavenger species that were feeding on the carcasses.

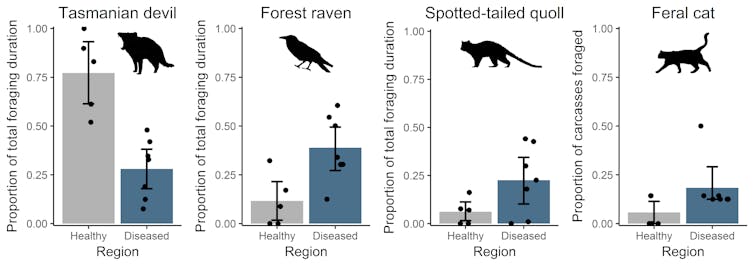

Unsurprisingly, far less carrion has been consumed by devils in areas where demon populations have declined. This has increased the availability of carrion for other species, such as the invasive wild cat, the spotted tail quail and the forest raven. All these species have greatly increased their cleaning in places with less devils.

Acts of the Royal Society B

The responses of the native scavengers (quolls and crows) were slightly different from those of wild cats. The amount of food provided by the quolls and crows depended simply on the amount of each carcass already consumed by the devils. Crows and quolls are smaller and less effective than demons in consuming carcasses. They therefore have the opportunity to feed only when the demons have not yet monopolized a carcass.

Read more:

The Tasmanian devils bred in captivity show that they can thrive in the wild

In contrast, wildcats tended to feed only on sites where devils were in very low abundance. This suggests that healthy devil populations create a "landscape of fear" that causes cats to completely avoid carcasses in areas where they may encounter the devil. It seems that the life of a wild cat is now less scary in the absence of devils.

Prevalence of predators

In reviewing 20 years of bird surveys conducted by BirdLife Australia, we also found that the chances of encountering a raven in Tasmania more than doubled from 1998 to 2017. We were not able to to establish a direct link with the devil's declines. It is likely that the population of crows is increasing due to many factors, including land-use change and intensification of agriculture, as well as the reduction of competition with demons.

Other studies have shown that cats have also become more abundant in areas where demons have declined. This highlights the potential of demons to act as natural biological control on cats. Cats are a major threat to small native animals and are involved in most Australian mammalian extinctions.

Carcass problems

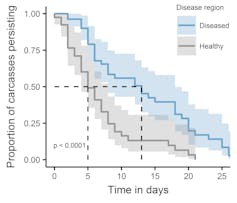

Although the smaller scavengers consumed more carrion as the devils declined, they were unable to consume them as quickly as the devils. This resulted in an accumulation of carcasses that would have been eaten quickly and completely by demons.

In places rich in devils, the carcasses were completely consumed in five days on average, compared to 13 days in places where the facial malignant disease of the devil rages. This means that carcasses last much longer where demons are rare.

<figure class = "align-this About 2 million medium-sized animals are killed by vehicles or slaughtered each year in Tasmania, and most are just left to decompose where they fall. As devils consume much less carrion, it is likely that carcasses accumulate in Tasmania. It is not known how much disease risk they pose to wildlife and livestock. Large carnivores are declining worldwide, with repercussions such as the increasing abundance of smaller predators. In recent years, some large carnivores have begun to return to their former ranges, giving hope that their lost ecological roles could be restored. Carnivores are declining for many reasons, but one of the underlying causes is that humans do not necessarily appreciate their vital role in the health of whole ecosystems. One way to change this is to recognize the useful services that they provide.

Read more: Our research highlights one of these benefits. This corroborates arguments that we should help the demon population to recover, not only for their own sake, but also for other species, including those threatened by wildcats. The devil seems to solve the problem of the disease itself, by rapidly developing a resistance to facial tumors. Any management plan should help this process and not hinder it. Returning devils to the Australian mainland could offer similar benefits to wildlife threatened by wild predators.

Calum Cunningham / Menna Jones

Keep carnivores

Tasmanian devils evolve rapidly to fight deadly cancer

[ad_2]

Source link