[ad_1]

Find the latest news and advice on COVID-19 in Medscape’s Coronavirus Resource Center.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

welcome to Impact factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I am Dr F. Perry Wilson from the Yale School of Medicine.

Wouldn’t it be nice if there was a COVID-19 treatment that was safe, effective, inexpensive, and out of the control of faceless pharmaceutical executives, more beholden to shareholders than to patients? The dream of such a magic solution has led to a number of similar claims that any given drug – or supplement, in some cases – has dramatic effects against COVID-19. We saw it first with hydroxychloroquine, but a similar hype surrounded vitamin D, ivermectin, melatonin, vitamin C and, of course, zinc.

What makes the claims so compelling are two things. One was a dose of biological plausibility. Biologists might argue that there was an underlying reason Why a given vitamin would help, usually citing beneficial effects on immune function or a reduction in inflammatory cytokines. But more than that, these drugs had an outsider history. These modest agents who have been with us for decades or more could become our most powerful ally against this scourge of the virus. The preliminary data was often run out of steam, but, as I pointed out about vitamin D, we had already been burned. Many of us wanted to see the randomized trials before we embarked on any of these potential treatments.

This week we had one of those trials, appearing in JAMA network open, examine the ability of zinc and vitamin C – alone or in combination – to shorten symptoms of COVID-19 in ambulatory patients.

It was a 2×2 factorial design, as you can see here. Patients were randomized to usual care or to one of the three treatment arms approximately equally.

.PNG)

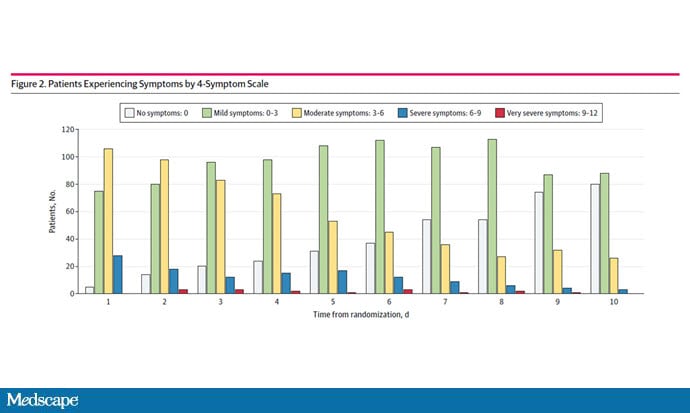

They were ambulatory patients, so we weren’t going to see a ton of difficult results. Instead, the researchers used a rank-based symptom scoring method. Each day, participants were asked about four symptoms, which they rated on a scale of 0 to 3, resulting in a symptom score between 0 and 12. The primary outcome was the time taken to halve the symptoms. symptom score; in other words, if you start at 4, the time it takes to get to 2; or if you start at 10, the time it takes to get to 5. This is a bit of a weird result, because it assumes a mathematical equivalence where I don’t think there is, but I guess it is. is as good as we can get.

Here are the symptoms over time for the entire study cohort. You can see a general decline in moderate symptoms (yellow) in favor of mild symptoms (green).

Thomas S, et al. JAMA Netw Open. 2021; 4: e210369. doi: 10.1001 / jamanetworkopen.2021.0369

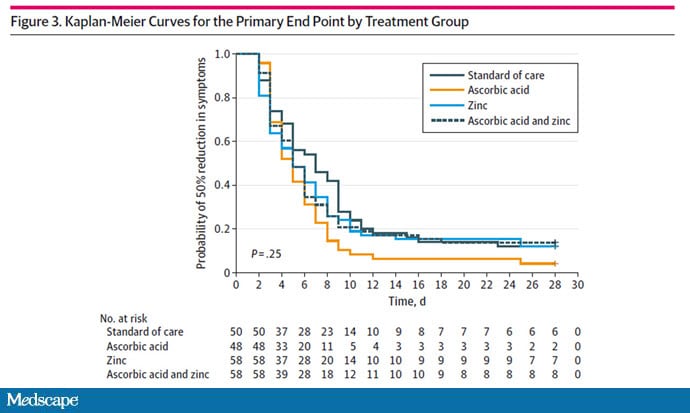

But when you stratified by treatment, the 50% symptom reduction time was basically the same across the board: around 5.5-6.5 days, depending.

Thomas S, et al. JAMA Netw Open. 2021; 4: e210369. doi: 10.1001 / jamanetworkopen.2021.0369

No individual symptom resolved faster with zinc, vitamin C, or the combo. Basically, the population looked like we expected: a few days of fever, with persistent cough and fatigue.

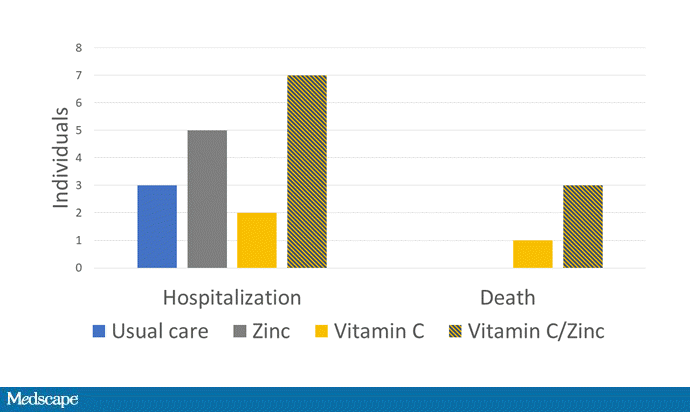

The hospitalization rate did not differ significantly, although it was slightly higher in the supplement groups. And thankfully, there were only three deaths – one in the vitamin C group and two in the combo group.

In terms of side effects, there was nothing crazy. But obviously, the authors saw more in the treatment groups than in the usual care group, mostly gastrointestinal stuff.

Now, zinc apologists will no doubt note the lack of a zinc ionophore (like chloroquine or pyrithione) as a reason it didn’t work. And again, I remind everyone that biological plausibility is not the end of medical research but the beginning; this is the minimum bar to be crossed to ethically conduct a definitive test, not an end in itself. I’ll be happy to do a read on any upcoming randomized hydroxychloroquine-zinc combo trials that emerge.

More broadly, I think we just have to come to terms with the fact that a cure for COVID is unlikely to be in our closets. Many chemicals have activity against pathogens in test tubes, just as many chemicals work in vitro against cancer. But this trial reminds us that more often than not, biologically promising agents do not survive the rigors of real-world testing. Be hopeful, but bring data.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is Associate Professor of Medicine and Director of the Yale Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator. Her science communications work can be found in the Huffington Post, on NPR, and here on Medscape. He tweets @fperrywilson and hosts a repository of its communication work on www.methodsman.com.

Follow Medscape on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and YouTube

[ad_2]

Source link