[ad_1]

Scientists have made clumps of human tissue that behave like early-stage embryos, a feat that promises to turn research into interim first steps in human development.

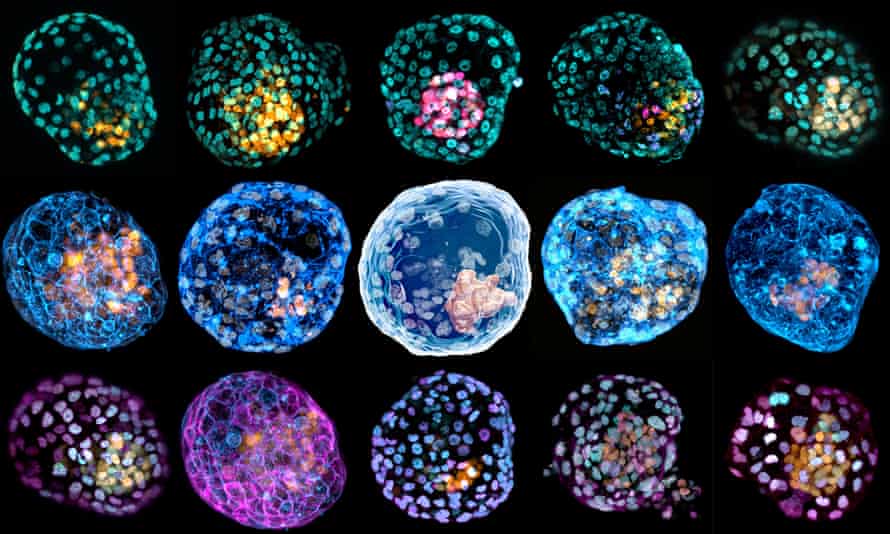

The clumps of cells, called blastoids, are less than a millimeter in diameter and look like structures called blastocysts, which form a few days after an egg is fertilized. Blastocysts usually contain around 100 cells, which give rise to all tissues in the body.

Two teams of researchers have found that they can make tiny blastoids from reprogrammed stem cells or skin cells by growing them in 3D wells filled with broth containing the chemicals necessary for normal blastocyst formation.

In separate articles published in Nature, scientists describe how cells self-assembled into ball-shaped blastoids after six to eight days of culture. Tests revealed that they contained all of the cells seen in natural blastocysts. Some continued to attach themselves to plastic culture dishes, mimicking the process of implantation in the uterus.

By studying blastoids, scientists hope to learn how newly formed embryos develop before implantation and understand why so many miscarriages occur at this delicate stage of human pregnancy.

Other work will use cells to understand how certain birth defects can arise and to study the impact of environmental toxins, drugs and even viral infections on healthy embryonic development.

“The ability to work at scale, we believe, will revolutionize our understanding of these early stages of human development,” said Professor José Polo, who led one of the teams at Monash University, Australia.

Until now, research into the early stages of human development has relied heavily on couples donating excess IVF embryos to science. This practice aroused ethical objections, and limited donations resulted in severe restrictions on progress for scientists. By law, researchers can only study human embryos until they are 14 days old.

The creation of blastoids is expected to overcome these problems by allowing scientists to make hundreds of embryo-like structures in the lab at a time.

“We’re very excited,” said Jun Wu, assistant professor at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas, Texas, and leader of a separate team. “Studying human development is really difficult, especially at this stage of development. It is essentially a black box. Wu said the blastoids were cultured to the equivalent of about 10 days for a human embryo.

Naomi Moris, from the Francis Crick Institute in London, which uses stem cells to model the development of the human embryo, called the work important and highlighted the rapid progress being made in this area. “The value of these models is that we can hopefully use them to begin to understand how normal human development takes place and what processes might be at play when things go wrong, miscarriage or death. birth defects for example, ”she said.

Polo and Wu said that while blastoids are similar to early stage embryos, they are not identical and can only mimic the first week of human development. The approach will not be used to make embryos for implantation, said Amander Clark, of the University of California, Los Angeles, who has worked with Polo.

But in a companion article in Nature, scientists at the University of Michigan suggested that scientific advancements would lead to blastoids that more closely mimic human blastocysts.

The scientists, Yi Zheng and Jianping Fu, wrote, “This will inevitably lead to questions of bioethics. What should be the ethical status of human blastoids and how should they be regulated? Should the 14 day rule apply? These questions will need to be answered before research on human blastoids can proceed with the required caution.

[ad_2]

Source link