[ad_1]

The Pfizer and Moderna vaccines are expected to become the mainstay of the COVID-19 vaccine rollout in Australia over the year, according to recently released government projections.

As of September, up to 1.3 million average doses of Pfizer vaccine and another 125,000 doses of Moderna vaccine, which has not yet been approved, are expected to be available per week. These numbers are expected to increase from October, as use of the AstraZeneca vaccine declines.

Both Pfizer and Moderna vaccines are mRNA vaccines, which contain tiny fragments of the genetic material known as “messenger ribonucleic acid”. And if social media is something to do, some people fear that these vaccines could affect their genetic code.

Here’s why the chances of that happening are next to zero, and some pointers on how the myth originated.

Remind me, how do mRNA vaccines work?

The technology used in the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines is a way to give your cells temporary instructions to make the coronavirus spike protein. This protein is found on the surface of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19. Vaccines teach your immune system to protect you if you ever come across the virus.

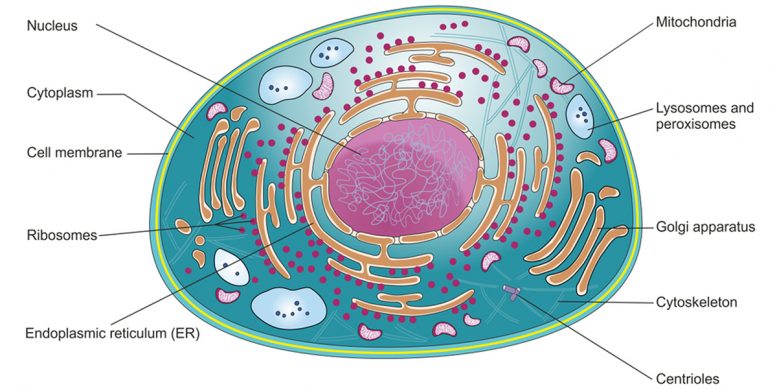

The mRNA from the vaccine is taken up by cells in your body and found in the fluid inside each cell called the cytoplasm. Our cells naturally make thousands of our own mRNAs all the time (to encode a range of other proteins). The vaccine mRNA is therefore just another. Once the vaccine mRNA is in the cytoplasm, it is used to make the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein.

The vaccine’s mRNA is short lived and breaks down quickly after it does its job, as it does with all of your other mRNAs.

The vaccine’s mRNA is in the cytoplasm and once it has done its job, it is broken down.

Here’s why mRNA can’t fit into your genetic code

Your genetic code is made up of a different but related molecule to the vaccine’s mRNA called DNA or deoxyribonucleic acid. And mRNA cannot fit into your DNA for two reasons.

First, the two molecules have different chemistry. If mRNAs could systematically fit into your DNA at random, it would wreak havoc on the way you make proteins. It would also scramble your genome, which is passed on to cells and future generations. The life forms that do this would not survive. That’s why life evolved for it do not happen.

The second reason is that the vaccine’s mRNA and DNA are found in two different parts of the cell. Our DNA stays in the nucleus. But the mRNA from the vaccine goes directly into the cytoplasm, never entering the nucleus. We do not know of any transport molecules that carry mRNA into the nucleus.

But are there no exceptions?

There are extremely rare exceptions. One is where genetic elements, known as retro-transposons, hijack cellular mRNA, convert it into DNA, and reinsert that DNA into your genetic material.

This has happened sporadically throughout evolution, producing old copies of mRNAs scattered throughout our genome, to form pseudogenes.

Some retroviruses, like HIV, also insert their RNA into our DNA, using methods similar to retro-transposons.

However, there is a very small chance that a natural retro-transposon will become active in a cell that has just received an mRNA vaccine. There is also a very small chance of getting infected with HIV exactly at the same time as receiving the mRNA vaccine.

There is a very low chance of getting infected with HIV at the same time as having an mRNA vaccine.

Even if a retro-transposon becomes active or a virus such as HIV is present, the chances of it finding the COVID vaccine mRNA, among the tens of thousands of natural mRNAs, are extremely unlikely. This is because the vaccine’s mRNA is broken down within a few hours of entering the body.

Even if the vaccine mRNA became a pseudogen, it would not produce the SARS-CoV-2 virus, but just one of the viral products, the harmless spike protein.

How do we really know this?

We are not aware of any studies looking for vaccine mRNA in the DNA of people who have been vaccinated. There is no scientific basis for suspecting that this insertion has occurred.

However, if these studies were to be done, they would have to be relatively straightforward. This is because we can now sequence DNA in individual cells.

But in reality, it will be very difficult to satisfy an opponent who is convinced that this insertion of the genome is taking place; they can always argue that scientists need to look deeper, harder, into different people and into different cells. At some point, this argument will have to be dropped.

So how did this myth come about?

One study reported evidence for the integration of coronavirus RNA into the human genome in laboratory-grown cells that had been infected with SARS-CoV-2.

However, this article did not examine the mRNA vaccine, lacked critical controls, and has since been discredited.

These types of studies must also be seen in the context of public distrust of genetic technology in general. This includes public concerns about genetically modified organisms (GMOs), for example, over the past 20 years.

But GMOs are different from the mRNA technology used to make COVID vaccines. Unlike GMOs, which are produced by inserting DNA into the genome, vaccine mRNA will not be in our genes or passed on to the next generation. It breaks down very quickly.

In fact, mRNA technology has all kinds of applications beyond vaccines, including biosecurity and sustainable agriculture. It would therefore be a shame if these efforts were hampered by disinformation.

Written by:

- Archa Fox – Associate Professor and ARC Future Fellow, University of Western Australia

- Jen Martin – Head of Science Communication Education Program, University of Melbourne

- Traude Beilharz – Associate Professor ARC Future Fellow, Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Monash Biomedicine Discovery Institute, Monash University

Originally posted on The Conversation.![]()

[ad_2]

Source link