[ad_1]

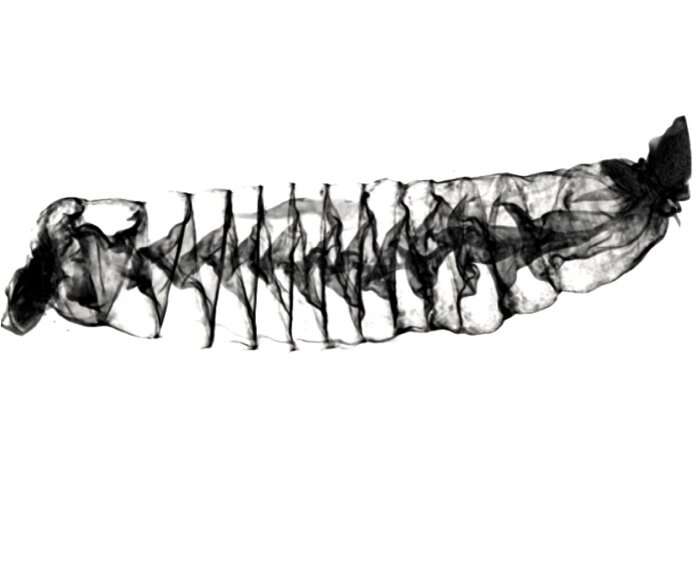

Computed tomography image of the spiral intestine of a Pacific Spiny Dogfish (Squalus suckleyi). The beginning of the intestine is on the left and the end is on the right. Credit: Samantha Leigh / California State University Dominguez Hills

Contrary to what the popular media portrays, we don’t know much about what sharks eat. Even less is known about how they digest their food and the role they play in the wider ocean ecosystem.

For more than a century, researchers have relied on flat sketches of sharks’ digestive systems to discern how they function and how what they eat and excrete impacts other species in the ocean. Today, researchers have produced a series of high-resolution 3D scans of the intestines of nearly three dozen shark species that will provide insight into how sharks eat and digest their food.

“It is high time that modern technology was used to examine these truly incredible spiral shark intestines,” said lead author Samantha Leigh, assistant professor at California State University Dominguez Hills. “We have developed a new method to digitally scan these tissues and can now examine soft tissues in so much detail without having to cut them out.”

The research team at California State University Dominguez Hills, the University of Washington and the University of California at Irvine, published their findings on July 21 in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

The researchers mainly used a computer tomography (CT) scanner at UW’s Friday Harbor Laboratories to create 3D images of shark intestines, from specimens held at the Natural History Museum in Los Angeles. The machine works like a standard CT scanner used in hospitals: a series of X-ray images are taken from different angles and then combined using computer processing to create three-dimensional images. This allows researchers to see the intricacies of a shark’s gut without having to dissect or disturb it.

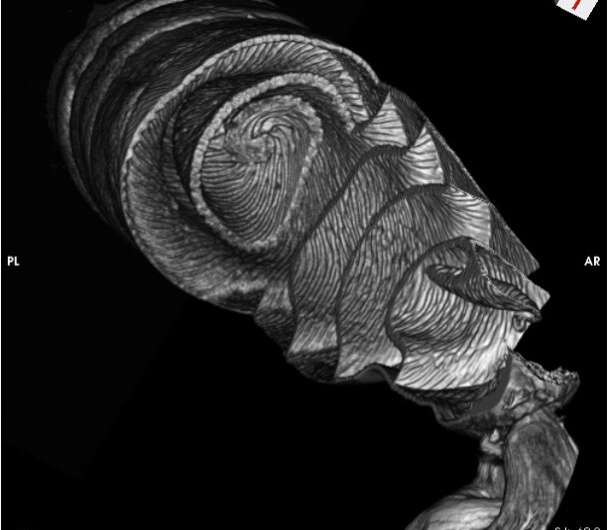

A CT image of a dogfish spiral intestine, shown from top to bottom. Credit: Samantha Leigh / California State University Dominguez Hills

“Computed tomography is one of the only ways to understand the shape of sharks’ intestines in three dimensions,” said co-author Adam Summers, a UW-based Friday Harbor Labs professor who led a global effort to scan the skeletons of fish and other vertebrate animals. “The intestines are so complex – with so many overlapping layers, that the dissection destroys the context and connectivity of the tissue. It would be like trying to figure out what was reported in a journal while taking scissors out of a rolled up copy. The story just won don’t hang out together. “

From their analyzes, the researchers discovered several new insights into how sharks’ intestines work. These spiral-shaped organs appear to slow the movement of food and direct it downward through the intestine, relying on gravity in addition to peristalsis, the rhythmic contraction of smooth muscle in the intestine. Its function resembles the one-way valve designed by Nikola Tesla over a century ago which allows fluid to flow in one direction, without backflow or assistance from any moving part.

This finding could shed new light on how sharks eat and process their food. Most sharks typically spend days or even weeks between large meals, so they rely on their ability to hold food in their system and absorb as many nutrients as possible, Leigh explained. The slower movement of food through their gut caused by the spiraling gut likely allows sharks to hold food for longer, and they also use less energy to process that food.

Because sharks are the ocean’s primary predators, and they also eat a lot of different things – invertebrates, fish, mammals and even seagrass – they naturally control the biodiversity of many species, the researchers said. Knowing how sharks process what they eat and how they excrete waste is important for understanding the ecosystem as a whole.

Two live Pacific acute sharks (Squalus suckleyi). Credit: Samantha Leigh / California State University Dominguez Hills

“The vast majority of shark species, and the majority of their physiology, are completely unknown. Every natural history observation, internal visualization, and anatomical investigation shows us things we might not have guessed,” Summers said. “We need to take a closer look at sharks and, in particular, we need to take a closer look at parts other than the jaws and species that do not interact with humans.”

The authors plan to use a 3D printer to create models of several different shark intestines to test how materials move through structures in real time. They also hope to collaborate with engineers to use shark intestines as inspiration for industrial applications such as treating wastewater or filtering microplastics out of the water column.

Monster shark movies undermine shark conservation efforts

Shark spiral intestines can function as Tesla valves, Proceedings of the Royal Society B , rspb.royalsocietypublishing.or… .1098 / rspb.2021.1359

Provided by the University of Washington

Quote: New 3D images of shark intestines show they function like Nikola Tesla’s valve (2021, July 20) retrieved July 20, 2021 from https://phys.org/news/2021-07-3d -images-shark-intestines-function.html

This document is subject to copyright. Other than fair use for private study or research purposes, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is provided for information only.

[ad_2]

Source link