[ad_1]

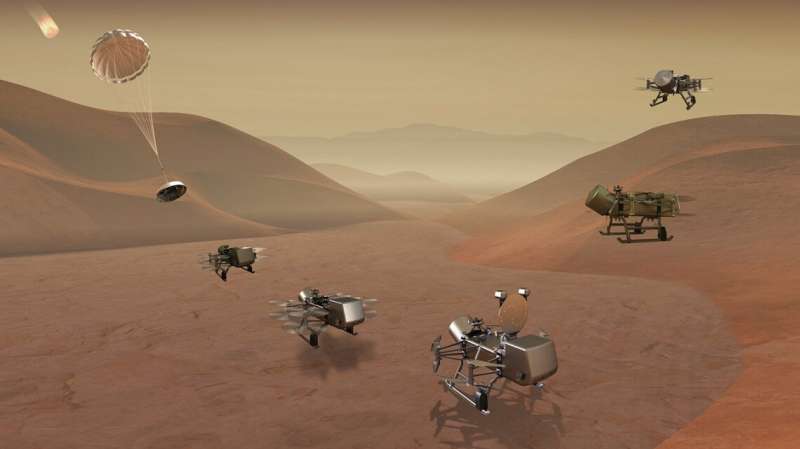

Concept illustration of the Dragonfly entry, descent, landing, surface operations and flight mission concept at Titan. Credit: Johns Hopkins / APL

Of the many moons in our solar system, Saturn’s Titan stands out – it is the only moon with a substantial atmosphere and liquid on the surface. It even has a weather system like Earth’s, although it rains methane instead of water. Can it also harbor some kind of life?

NASA’s Dragonfly mission, which will send a movable rotorcraft lander to the surface of Titan in the mid-2030s, will be the first mission to explore the surface of Titan, and it has big goals.

On July 19, the Dragonfly science team published “Science Goals and Objectives for the Dragonfly Titan Rotorcraft Relocatable Lander” in The Journal of Planetary Sciences. The lead author of the article is Jason Barnes, Associate Principal Investigator at Dragonfly and Professor of Physics at the University of Idaho.

Dragonfly’s goals include research for chemical biosignatures; investigate the moon’s active methane cycle; and explore the prebiotic chemistry currently taking place in Titan’s atmosphere and on its surface.

“Titan represents an explorer’s utopia,” said co-author Alex Hayes, associate professor of astronomy at the College of Arts and Sciences and co-investigator of Dragonfly. “The scientific questions we have for Titan are very broad because we don’t yet know much about what is really happening on the surface. For every question we answered during the Cassini mission’s exploration of Titan since Saturn’s orbit, we’ve gained 10 new ones. “

Although Cassini has been orbiting Saturn for 13 years, the thick methane atmosphere on Titan made it impossible to reliably identify materials on its surface. While Cassini’s radar allowed scientists to penetrate the atmosphere and identify Earth-like morphological structures, including dunes, lakes and mountains, the data could not reveal their makeup.

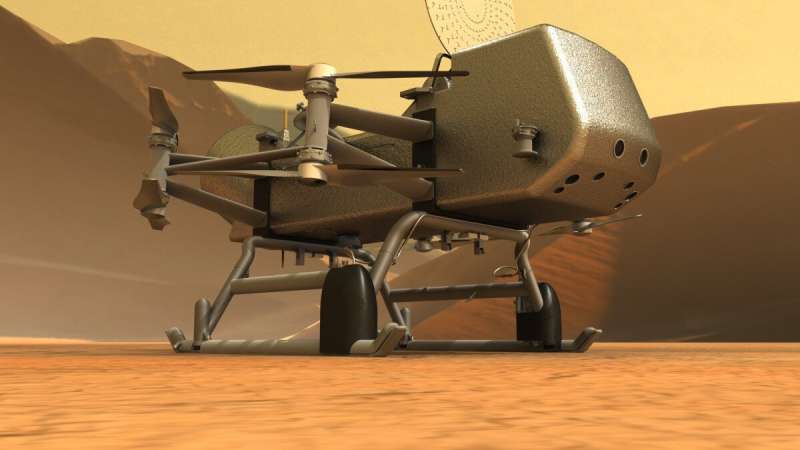

NASA’s Dragonfly mission, which will send a movable rotorcraft lander to the surface of Titan in the mid-2030s, will be the first mission to explore the surface of Titan. Credit: Johns Hopkins / APL

“In fact, at the time Cassini was launched, we weren’t even sure if Titan’s surface was a global liquid ocean of methane and ethane, or a solid surface of water ice and solid organic matter,” said Hayes, also director of the Cornell Center for Astrophysics and Planetary Science and the Spacecraft Planetary Image Facility at A&S.

The Huygens probe, which landed on Titan in 2005, was designed to float in a sea of methane / ethane or to land on a hard surface. His science experiments were mostly atmospheric, as they weren’t sure he would survive the landing. Dragonfly will be the first mission to explore the surface of Titan and identify the detailed makeup of its organic-rich surface.

“What’s so exciting to me is that we’ve been making predictions about what’s going on locally on the surface and how Titan works as a system,” Hayes said, “and the images and Dragonfly’s measurements will tell us how wrong they are. “

Hayes has worked on Titan for most of his career. He is particularly keen to answer some of the questions raised by Cassini in the area of his specialty: planetary surface processes and surface-atmosphere interactions.

“My main scientific interests are to understand Titan as a complex Earth-like world and to try to understand the processes that govern its evolution,” he said. “It involves everything from the interactions of the methane cycle with the surface and the atmosphere, to the routing of materials through the surface and potential exchanges with the interior.”

Hayes will also bring significant expertise in another area: the operational experience of rover missions to Mars.

Artist’s impression of Dragonfly in flight over Titan. Credit: Johns Hopkins / APL

“The Dragonfly mission benefits and represents the intersection of Cornell’s substantial history with rover operations and Cassini science,” said Hayes. “He brings these two things together as he explores Titan with a movable moving ship.”

Cornell astronomers are currently involved in the Mars Science Laboratory and Mars 2020 missions, and led the Mars Exploration Rovers mission. Lessons learned from those Mars rovers are being transferred to Titan, Hayes said.

Dragonfly will spend a full Titan day (equivalent to 16 Earth days) in one location to conduct scientific experiments and observations, then fly to a new location. The science team will need to make decisions on what the spacecraft will do next based on lessons learned from the previous location, “which is exactly what Martian rovers have been doing for decades,” said Hayes.

Titan’s low gravity (about one-seventh that of Earth) and its thick atmosphere (four times as dense as Earth’s) make it an ideal location for an aerial vehicle. Its relatively calm atmosphere, with winds lighter than Earth, makes it even better. And while the science team doesn’t expect rain during Dragonfly’s flights, Hayes noted that no one really knows the local weather conditions on Titan, yet.

Many of the scientific questions outlined in the group’s article relate to prebiotic chemistry, an area of great interest to Hayes. Many of the prebiotic chemical compounds that formed on early Earth also formed in Titan’s atmosphere, and Hayes is eager to see how far Titan has actually gone on the prebiotic chemistry road. Titan’s atmosphere could be a good analog for what happened on early Earth.

Dragonfly’s research for chemical biosignatures will also be extensive. In addition to examining Titan’s habitability in general, they will study potential chemical biosignatures, past or present, from water-based life to one that could use liquid hydrocarbons as a solvent, such as in its lakes, seas. or its aquifers.

The recipe is different, but Saturn’s moon Titan has ingredients for life

Jason W. Barnes et al, Science Goals and Objectives for the Dragonfly Titan Rotorcraft Relocatable Lander, The Journal of Planetary Sciences (2021). DOI: 10.3847 / PSJ / abfdcf

Provided by Cornell University

Quote: Dragonfly Mission to Titan Announces Big Science Goals (2021, August 10) retrieved August 10, 2021 from https://phys.org/news/2021-08-dragonfly-mission-titan-big-science.html

This document is subject to copyright. Other than fair use for private study or research purposes, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is provided for information only.

[ad_2]

Source link