[ad_1]

Scientists have discovered a gigantic prehistoric limulus relative in the 500-million-year-old Burgess Shale in Canada, according to a study published Wednesday in the Royal Society Open Science. The creature is believed to have been one of the largest of its time, surpassing other prehistoric crabs previously discovered.

Paleontologists at the Royal Ontario Museum named the new species Titanokorys gainesi and dated it to the Cambrian Period – part of an era between 541 and 485.4 million years ago that produced the explosion of most intense evolution ever. While most ocean organisms from this period were no bigger than a little finger, the Titanokorys were over half a meter long.

“The size of this animal is absolutely breathtaking, it is one of the largest animals of the Cambrian period ever found”, Jean-Bernard Caron, Richard M. Ivey curator of the museum of invertebrate paleontology and associate professor in ecology and evolution. biology and earth sciences at the University of Toronto, said in a press release.

Royal Ontario Museum

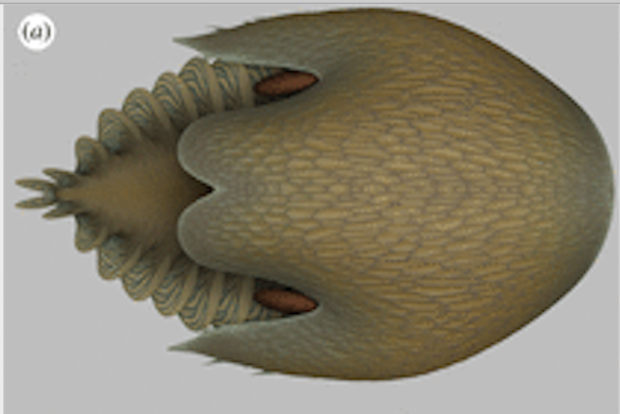

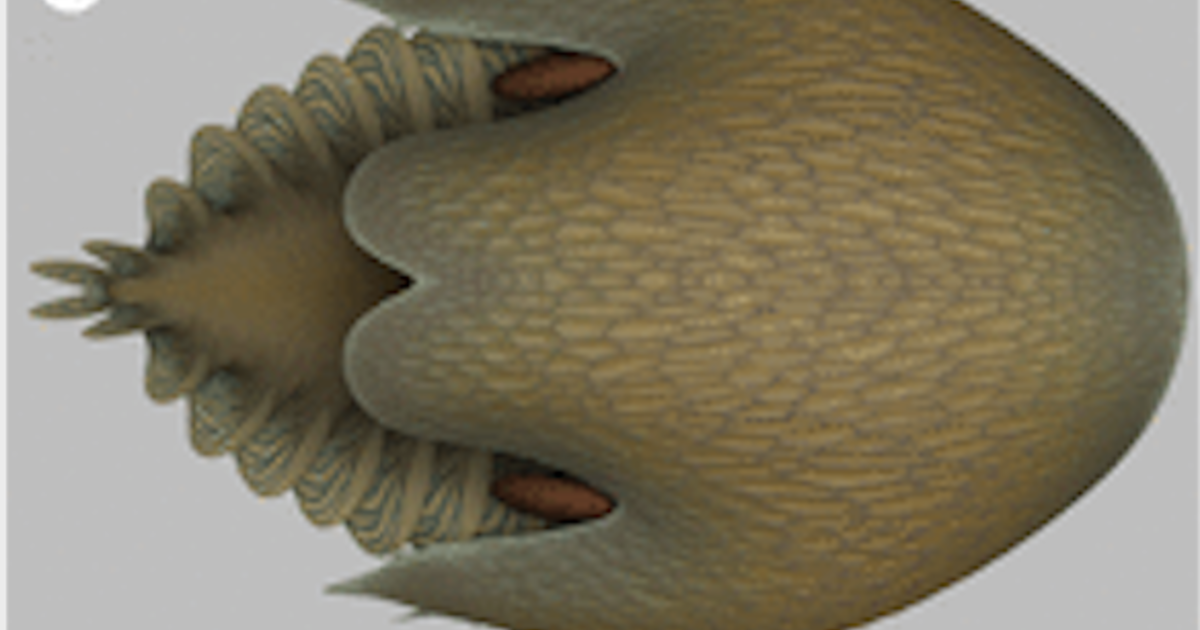

Both Titanokorys and Anomalocaris were radiodons, which were primitive arthropods with “multifaceted eyes, a mouth shaped like a pineapple slice and lined with teeth, a pair of thorny claws under its head to capture prey. and a body with a series of flaps for swimming. “, according to the press release.

“These enigmatic animals certainly had a big impact on the ecosystems of the Cambrian seabed. Their front limbs looked like several stacked rakes and would have been very effective in bringing whatever they caught in their tiny thorns back to their mouths.” , added Caron.

Some radiodont species also had large head shells – or defensive shells – and Titanokorys have one of the largest ever found. Unfortunately, scientists don’t fully understand why some radiodons have “such a bewildering array” of shell sizes and shapes, but Titanokorys’ broad, flat head was likely designed to help them forage deep in the sea. ocean.

Royal Ontario Museum

“The head is so long in relation to the body that these animals are actually little more than swimming heads,” said Joe Moysiuk, co-author of the study and a doctorate in a museum. studying ecology and evolutionary biology at the University of Toronto, said in the statement.

The Burgess Shale, located in Kootenay National Park of Canada, was discovered less than 10 years ago. However, scientists have already found many small parents of Titanokorys with similarly shaped head shells in the region. According to paleontologists, Titanokorys and its relatives may have competed for similar prey living at the bottom.

[ad_2]

Source link