[ad_1]

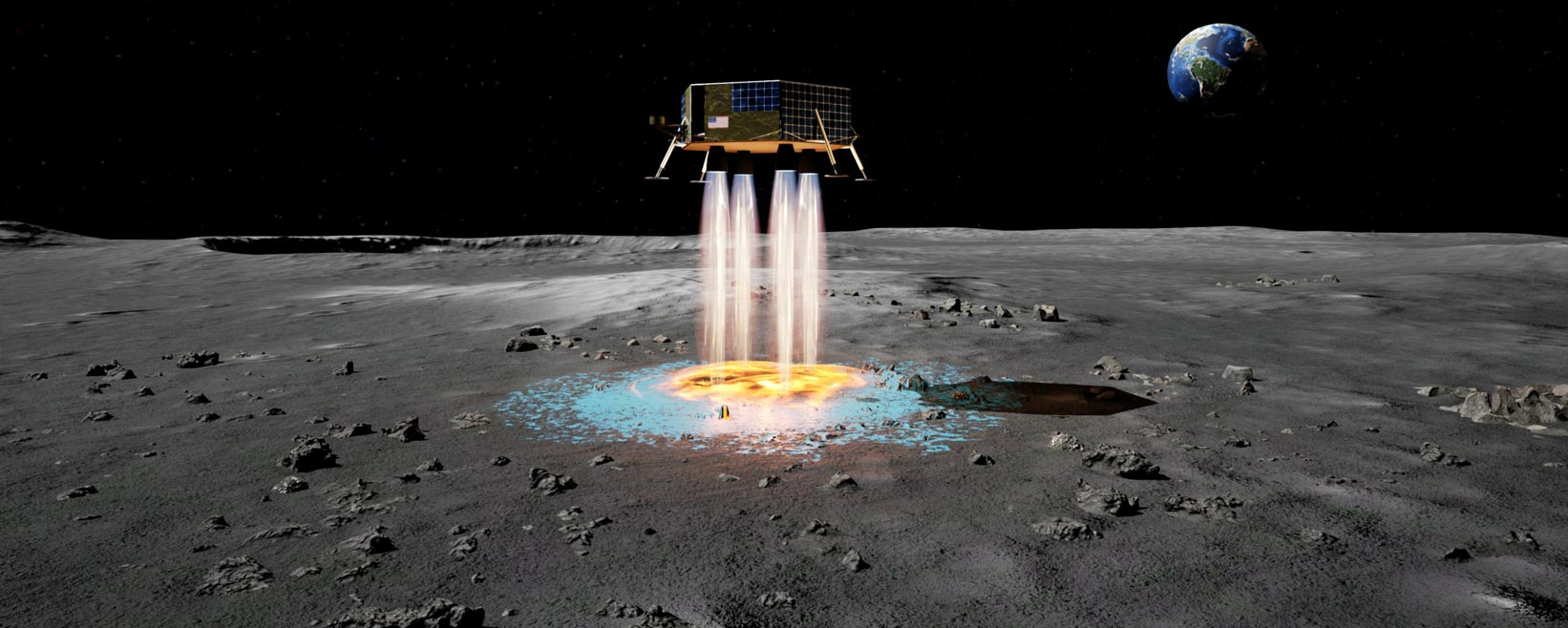

The artistic depiction of a lunar lander uses the deposition technology of a FAST landing pad. Credit: Masten Space Systems

Space exploration requires all kinds of interesting solutions to complex problems. There is a branch of Nasa designed to support innovators trying to solve these problems – the Institute for Advanced Concepts (NIAC). They sometimes give grants to worthy projects that attempt to address some of these challenges. The results of one of these grants are now available and they are intriguing. A team from Masten Space Systems, supported by Honeybee Robotics, Texas A&M, and the University of Central Florida, found a way for a lunar lander to drop off its own landing pad on the way down.

Moon dust is a major problem for all powered landers on the surface. The retrograde rockets needed to gently land on the moon’s surface will also throw dust and swing through the air, potentially damaging the lander itself or any surrounding human infrastructure. A landing pad would reduce the impact of this dust and provide a more stable place for the landing itself.

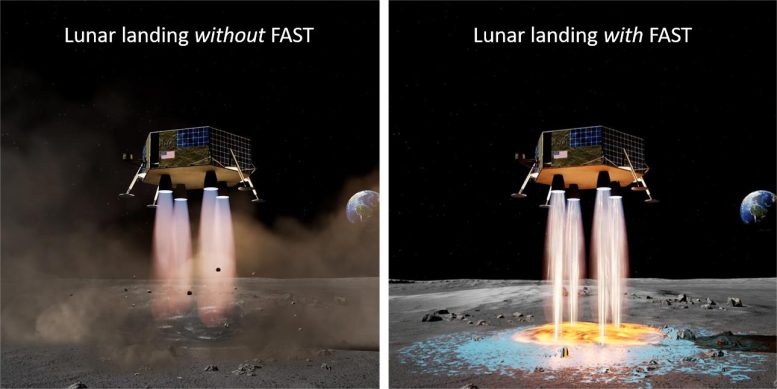

Graph showing the difference between landing with or without the depot system. Credit: Masten Space Systems

But building such a landing pad in the traditional way would be prohibitively expensive. Current estimates put the cost of building a lunar landing pad using traditional materials at around $ 120 million. Such a mission also suffers from a chicken and egg problem. How do you put in place the materials to build the airstrip if there is no airstrip, to begin with?

The technology developed by Masten is an ingenious solution to these two problems. Laying down a landing pad during descent would allow astronauts to have a landing pad in place before a spacecraft lands on it. It would also cost a lot less to install as all that is needed is a relatively simple additive to the rocket exhaust already thrown into the surface.

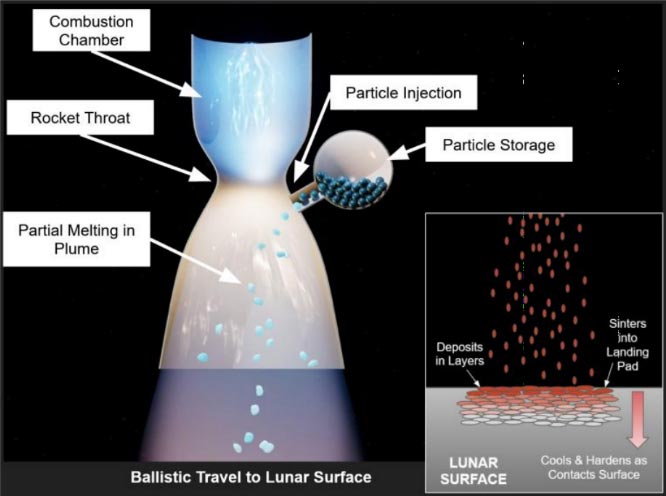

Graphic showing the whole process of the FAST particle injector system. Credit: Masten Space Systems

Masten’s general idea is quite easy to understand. Adding solid pellets to the rocket exhaust would allow this material to partially liquefy and settle on the exhaust blast area, potentially hardening it to a point where dust is no longer a factor because it is encapsulated in a hard outer shell. Masten thought he could find the right material to add to rocket exhaust to do just that.

Success or failure would depend on the physical properties of the additive pellets. Any additive with too much heat tolerance would not melt properly in the rocket exhaust, essentially bombarding the surface with tiny bullets. On the other hand, any additive that is too poorly tolerant of heat could be completely melted by the rocket exhaust and vaporized into an unnecessary cloud.

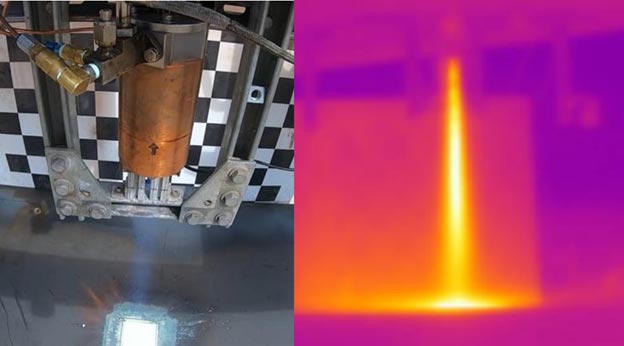

Example of the amount of dust that can be raised even on Earth during the test firing of one of Masten’s rockets. Credit: Masten Space Systems

To find the perfect balance, Masten developed a two-tier system, with relatively large (0.5mm) alumina particles used to create a 1mm base layer of molten lunar surface combined with alumina. . Then, as the lander got closer to the base layer, the additive would change to a 0.024mm alumina particle, which would settle at 650m / s on the base layer and create a landing pad. 6m in diameter that would cool in 2.5 seconds.

It all sounds like a pretty impressive idea, but it’s still early days. Like many federal grants, the NIAC grant focused on developing this depositable landing platform idea takes a phased approach. Most of Phase I, which just ended, has focused on demonstrating the feasibility of the idea, which Masten thinks it is.

Example of the effects of an alumina plate, similar to what would be deposited on the surface of the moon in a fully enlarged system. An infrared image of the rocket exhaust can be seen to the right. Credit: Masten Space Systems

Feasible isn’t the same as functional, but that’s precisely what NIAC grants are supposed to support – crazy ideas that might just fundamentally change some aspect of space exploration. If Masten is correct and the approach is possible and can be enlarged, landing platforms could appear all over the lunar surface. And finally everywhere March also.

[ad_2]

Source link