[ad_1]

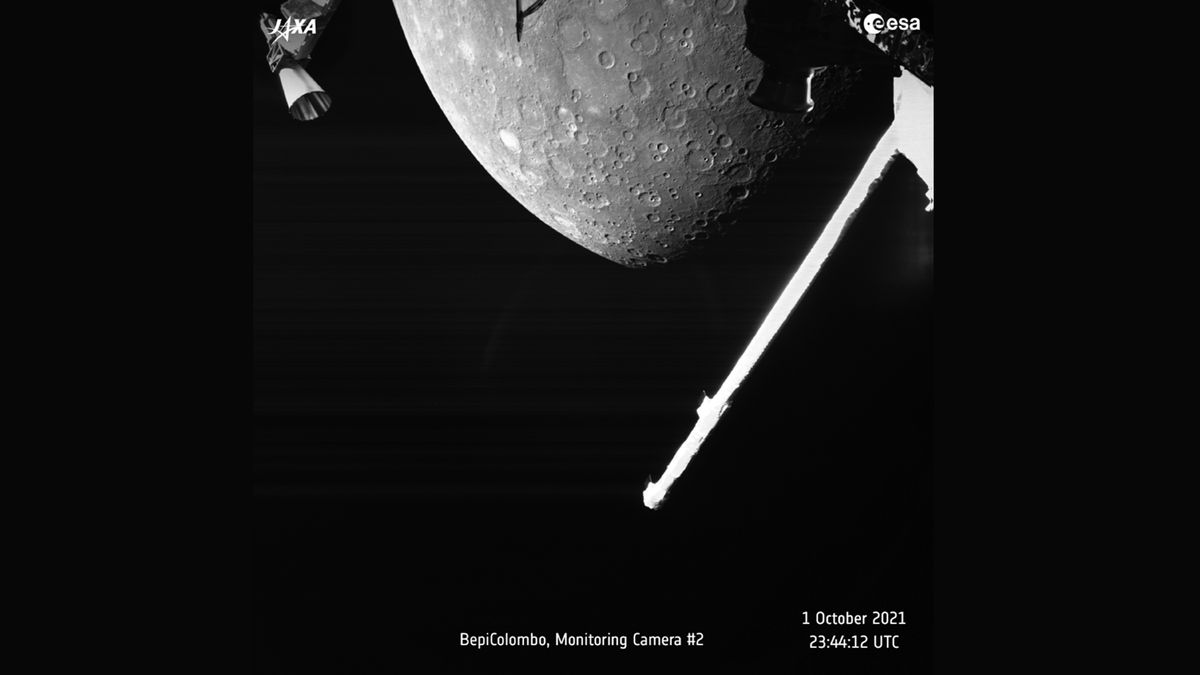

European and Japanese spacecraft BepiColombo made the closest ever measurements of Mercury’s magnetic field over the planet’s southern hemisphere as it passed by, taking epic selfies along the way.

European Space Agency (ESA) and Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) scientists are still processing the data that will present the first small contribution of the BepiColombo mission to unravel the mysteries of the smallest and most intimate planet of the solar system.

The flyby, carried out on Friday (October 1), was designed to slow BepiColombo in its orbit around the sun using the gravity of Mercury. Five more such overflights will be needed before the spacecraft can finally enter orbit around the planet in 2025.

During the flyby, three surveillance cameras on the spacecraft’s transfer module photographed the planet, with the results being released as a short video on Monday (October 4). This sequence of 53 images taken at distances of 620 to 57,800 miles (1,000 to 93,000 kilometers) represents BepiColombo’s first glimpse of its target planet.

Related: Mercury may not have declined as much as scientists think

During the flyby, BepiColombo approached the surface of Mercury at a distance of 120 miles (200 km), which is closer than its ultimate scientific orbit around the planet of 300 to 930 miles (480 to 1,500 km). ). The closest approach, however, occurred from the night side and could not be captured by cameras, ESA BepiColombo project scientist Johannes Benkhoff told Space.com.

“For us it was of course fantastic to see our planet for the first time,” said Benkhoff. “We now have our goal in mind and will use what we did during this flyby to fine-tune our parameters for even better results on future flyovers.”

BepiColombo consists of two orbiters that will circle Mercury separately – the ESA-made Mercury Planetary Orbiter (MPO) and JAXA’s Mercury Magnetospheric Orbiter (MMO) – that travel to Mercury stacked on top of a transfer module. This setup, however, blocks some of the mission’s instruments, including high-resolution cameras on MPO, limiting the possible science during overflights.

The black and white “selfie” cameras used in this flyby were originally intended to monitor the deployment of the spacecraft’s solar panels after its launch in 2018. These cameras provide images with a modest resolution of 1024 x 1024 pixels (comparable to a flip phone from the early 2000s). , which, according to Benkhoff, still reveals some of the interesting features of Mercury’s surface.

“The resolution of our surveillance cameras is not as good as that of the science cameras we have on board, so we were happy to have been able to identify some features on the surface,” said Benkhoff. “We can see differences in color, we can see shiny features that indicate a younger material, for example the Lermontov crater with hollows.”

The hollows are small bumps on the surface of Mercury discovered by NASA’s Messenger mission, the first and so far the only mission to orbit Mercury, which it did from 2011 to 2015. These troughs appear young, scientists say, and could be an indication of evaporation from matter of the interior of the planet. The BepiColombo team hopes to pick up where Messenger left off and compare the images of the hollows obtained by the two spacecraft. That task, however, must wait for images from high-resolution cameras, Benkhoff said.

Nonetheless, data from the October 1 flyby may still add new information to the scientific understanding of Mercury.

“Messenger followed an elliptical orbit, which brought it very close to the surface of Mercury in the northern hemisphere,” Benkhoff said. “With this overflight, we were close to the surface in areas that Messenger was still far away from.”

Scientists are now examining data from BepiColombo’s magnetometer, which could reveal new information about the planet’s weak magnetic field. Mercury’s magnetic field was a surprise discovery made by NASA Mariner 10 spacecraft, which made three overflights of Mercury in the 1970s and obtained the first near-planet images.

Scientists did not expect Mercury to have a magnetic field at all due to the small size of the planet. Of the four rocky planets of the inner solar system, only Earth has a strong magnetic field, which protects it from cosmic radiation and bombardment by cosmic particles. March probably had a magnetic field in the past, but lost it at some point causing the planet to lose its atmosphere.

Instead, not only does Mercury have a magnetic field, it’s also weird. “The Messenger spacecraft subsequently discovered that Mercury’s magnetic field is shifted north by 20% of the planet’s radius,” Benkhoff said. “By probing the south, we might be able to confirm this change or see that it might be a little less offset.”

Scientists at BepiColombo also hope to measure the magnetization of Mercury’s dried crust and see how it interacts with the main magnetic field.

The flyby provided the first opportunity to test the spacecraft’s performance under the harsh conditions around Mercury that the two orbiters will have to withstand during their planned one-and-a-half-year missions. (MPO is expected to withstand temperatures of up to 840 degrees Fahrenheit, or 450 degrees Celsius, during its mission, which is hot enough to melt lead.) Due to this high temperature, some instruments that may otherwise be used in the cruise configuration were not allowed to take action because operators were concerned about the impact of the heat.

“The experience of this overflight will give us more operational safety for the next five overflights of Mercury that we must complete before we can finally enter orbit around Mercury,” said Benkhoff. “We hope that as we understand the temperatures around the spacecraft better, we may be able to use more instruments in future overflights.”

BepiColombo’s next meeting with Mercury will take place in June 2022 at a similar distance to the recent one. Four additional overflights will take place in June 2023, September 2024, December 2024 and January 2025.

Mercury is notoriously difficult to reach. Although the moon-sized planet is on average 10 times closer to Earth than Jupiter That is, a mission to Small World orbit requires about the same cruising time as a mission to the gas giant. This is because a mission to Mercury must constantly brake against the gravitational pull of the sun. This braking could theoretically be achieved with thrusters, but this operation would require an enormous amount of fuel. Instead, the spacecraft takes a long, roundabout route, taking advantage of the gravity of celestial bodies along the way to release energy and hit its target at the correct speed.

BepiColombo has already made a fly over the earth in April 2020 and two to Venus in October 2020 and August 2021.

Follow Tereza Pultarova on Twitter @TerezaPultarova. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

[ad_2]

Source link