[ad_1]

The air on our planet during the pre-industrial era was not as pure as one might think, according to new research in Antarctica.

An analysis of six ice drill holes taken from the southernmost continent revealed a substantial increase in carbon black from the 14th century onwards.

This is long before humans in the southern hemisphere began to burn coal, meaning the pollution likely came from pre-industrial fires feeding on natural biomass. Over the past 700 years, emission levels appear to have increased steadily, eventually tripling in number.

When the researchers modeled the potential flux of carbon black particles, they tracked the soot to Tasmania, New Zealand or Patagonia. While Tasmania and Patagonia were first settled by humans, the Maori people settled in New Zealand in the late 13th century, just as this carbon black began to appear in the archives. Antarctic ice cores.

The island nation’s palefire records also align with this timeline, suggesting that the burning of land in New Zealand was responsible for the large-scale distribution of the soot.

The initial mass migration to New Zealand must have been large enough to have such an immediate and widespread impact, the researchers say.

“The idea that humans at this time in history caused such a large change in atmospheric carbon black through their clearing activities is quite surprising,” says atmospheric scientist Joe McConnell of the Desert Research Institute ( DRI) in Nevada.

We once thought that human impacts on Earth’s atmosphere or our planet’s climate before the Industrial Revolution were negligible. Studies like these contribute to a growing awareness that our ability to change environments on a large scale is not a strictly modern phenomenon.

New Zealand was the last habitable place on Earth to be inhabited by people. When the Maori arrived, the forest cover was around 85 percent. Today, it’s around 25 percent, and research suggests these forests have been lost or eroded within decades of human habitation.

Already seven hundred years ago, it seems that the Maori systematically burned the native forests, which had little experience with fire and easily succumbed to the new force.

(Jack Triest)

(Jack Triest)

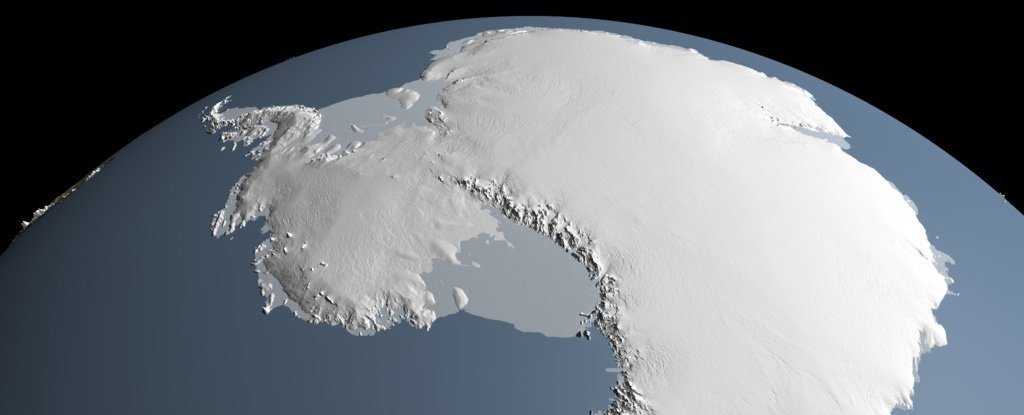

Above: The James Ross Island core drilled to bedrock in 2008 by the British Antarctic Survey provided an unprecedented record of soot deposition in the northern Antarctic Peninsula. Robert Mulvaney led the pit collection.

As evidenced by the ice cores, the black carbon from these fires reached Antarctica. Based on what we can see today, emissions appear to have peaked in the 16th century, reaching around 36,000 tonnes per year.

To put this into perspective, in 2019, the world’s energy-related CO2 emissions reached 33 gigatonnes, more than a million times more.

Yet even this relatively small amount of black carbon has eclipsed other human emissions in the region over the past 2,000 years, affecting some of the most remote parts of our planet.

Not only did soot smoke settle in Antarctica, but micronutrients from those fires likely also spilled into the South Pacific, feeding plankton thousands of miles away.

“Compared to natural burning in places like the Amazon, Southern Africa or Australia, you wouldn’t expect the Maori burning in New Zealand to have a big impact, but it does. on the Southern Ocean and the Antarctic Peninsula ”, explains a hydrologist. Nathan Chellman, also of DRI.

“Being able to use the ice core recordings to show the impacts on atmospheric chemistry that reached the entire Southern Ocean, and being able to attribute this to the arrival and settlement of the Maori in New Zealand 700 years ago was Truly unbelievable.”

Not only do the results give us a better baseline against which to measure current industrial activity, but they also reveal truths about New Zealand’s early settlers and when they arrived in this great southern country.

Just a few months ago, a study in New Zealand found that widespread deforestation started by the Maori and continued by white settlers today has already caused some insects to lose their ability to fly.

After all, without the surrounding forests to protect them, the winds of change could easily sway a flying insect from its path. The current study suggests once again that we are the huffers and huffers.

The study was published in Nature.

[ad_2]

Source link