[ad_1]

Mars’ Gale Crater may not have been so wet after all, a new study suggests.

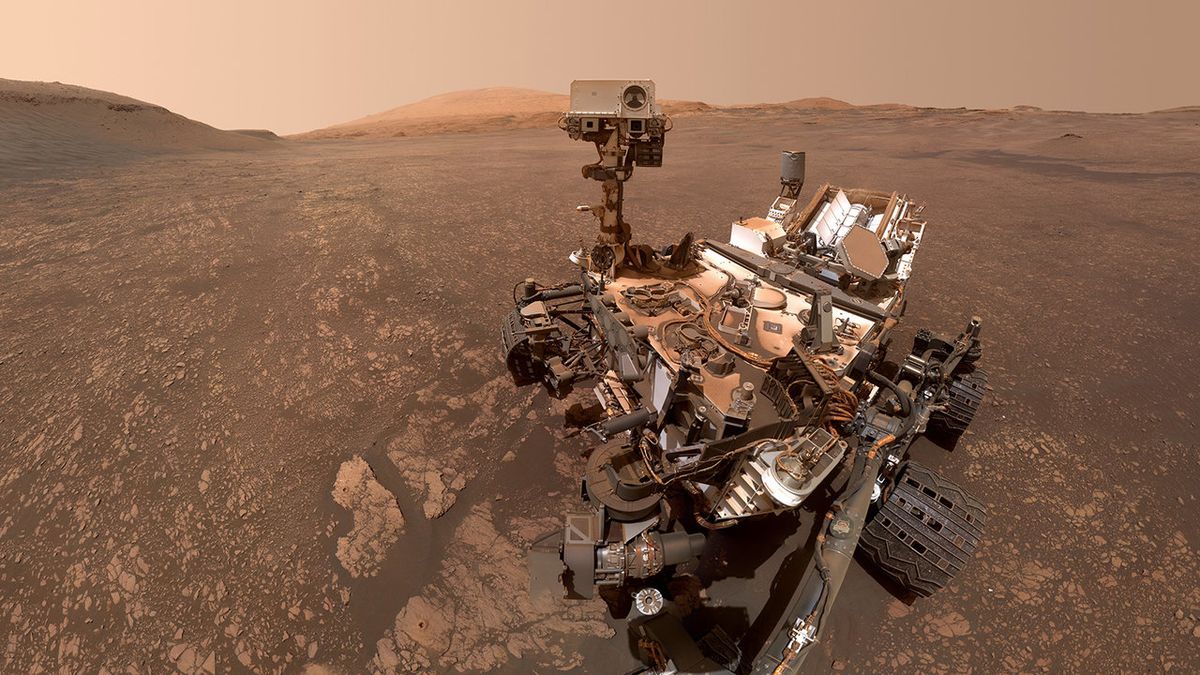

that of NASA Curiosity rover landed inside the 96-mile-wide (154-kilometer) Gale in August 2012, as part of a mission to assess the region’s past survival potential.

At a location near its Mars landing site called Yellowknife Bay, the car-sized robot found fine-grained “mudstone” sediment – solid evidence of an ancient lake. As it roamed the crater over the months and years that followed, Curiosity spotted more and more signs of past liquid water, which led the rover team to conclude that Gale hosted a large lake about 3.7 billion years ago.

Related: Stunning photos of Mars by NASA’s Curiosity rover

“This lake was large enough to have been able to last for millions of years – enough time for life to start and flourish, enough time for sediment from the lake to accumulate and form Mount Sharp,” Michael Meyer, scientist principal of the Mars exploration program at NASA headquarters in Washington, said at a press conference in December 2014.

Mount Sharp is the giant mound that rises approximately 3.4 miles (5.5 kilometers) into the Martian sky from central Gale. Its existence is one of the reasons NASA sent Curiosity to Gale: Since September 2014, the rover has been rolling down the slopes of the mountain, reading its many rock layers in search of clues to the changing history of the climate. Of March.

A new study, however, offers a different interpretation of Curiosity’s data and Gale’s past.

While the Yellowknife Bay mudstones were likely deposited in an ancient lake, the “majority of the stratigraphic section is interbedded sandstone and mudstone-sandstone, which is intensely weathered but probably not lacustrine. [lake-related] originally based on the suite of sedimentary structures, mineralogy and geochemical trends observed as a geological formation, ”researchers led by Hong Kong University (HKU) doctoral student Jiacheng Liu wrote in the paper, which was published today (August 6) in the journal Science Advances.

Liquid water caused this alteration, but it did not happen in a lake, suggest Liu and his colleagues. They offer a different scenario: most of the deposits examined by Curiosity entered the crater via wind and / or volcanic activity, and then were weathered by acid rain.

“This is most likely a chemical alteration caused by precipitation from a ground-like environment,” study co-author Joe Michalski, deputy director of the Space Research Laboratory, told Space.com. HKU and Liu’s doctoral advisor.

The data collected by Curiosity, which is still so strong today, point to the existence of a handful of small lakes in Gale long ago rather than a single large one, Michalski said. These small lakes were probably relatively transient, persisting for a few tens of thousands of years at a time, he added.

If Liu, Michalski, and their HKU co-author Mei-Fu Zhou – neither of whom are members of the Curiosity Mission team – are correct, then perhaps life has been more difficult to get started in Gale. than scientists thought. After all, the larger and more sustainable an environment that is conducive to life, the better the chance that chemistry will produce something complex and interesting in it.

This interpretation also has other consequences. For example, it stings Gale Crater as less aberrant than is generally believed, and therefore more representative of ancient Mars as a whole. And that’s an exciting prospect, said Michalski.

“It means we understand environmental conditions in a broader sense, looking at something that is much more average,” he said.

We could get more clarity on the Gale Lake issue fairly quickly, added Michalski, courtesy of Curiosity’s cousin. Perseverance. Perseverance landed last February on the floor of Mars’ 28-mile-wide (45 km) Jezero Crater to search for signs of ancient life and collect samples for future return to Earth, among other tasks. (Perseverance is now collects its very first Red Planet sample, in reality.)

Jezero’s soil certainly hosted an important, albeit transient, lake a long time ago, Michalski said.

“I suspect the sediments will be different,” he said. “So we can look at these two things side by side and say, ‘OK, buddy: this is what we see in a lake, and this is what we see in Gale. And they don’t look alike. ‘”

Mike Wall is the author of “The low“(Grand Central Publishing, 2018; illustrated by Karl Tate), a book on the search for alien life. Follow him on Twitter @michaeldwall. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or Facebook.

[ad_2]

Source link