[ad_1]

In early August, sailors from the southwestern Pacific Ocean began to see their environment metamorphose. As far as the eye can see, the ocean has gone from azure delight to a colossal gathering of floating and shaking rocks. And then came the sulphurous odors.

These rocks, some the size of a human head, were easy to pick up by hand. They were quickly recognized as pumice, volcanic debris filled with holes and pockets of trapped gas that give them a buoyancy in the water.

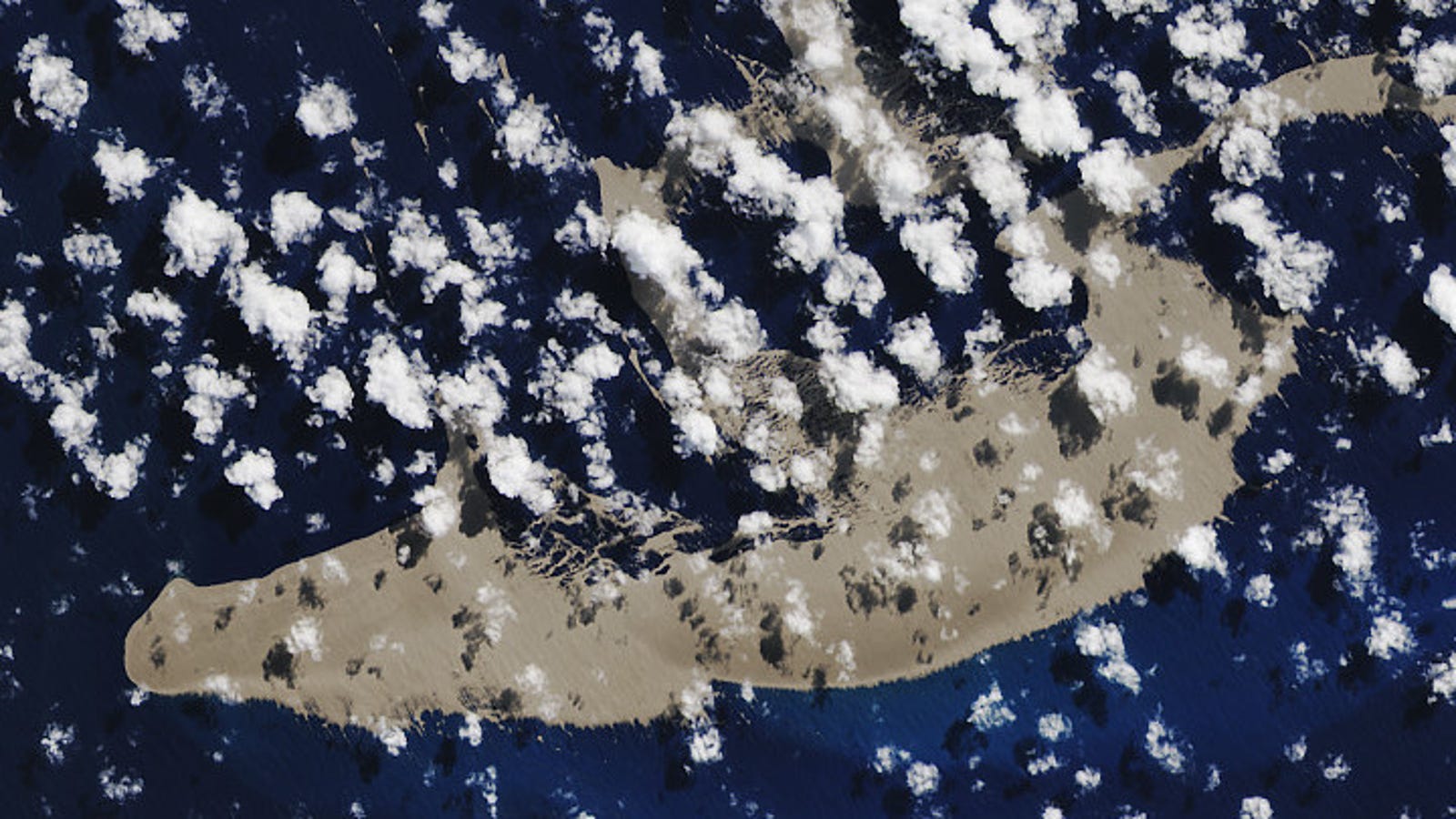

Satellite images – many of which were shared on Twitter by Simon Carn, a volcanologist at Michigan Technological University – showed a giant pumice raft torsion and warping in the open sea, driven by winds and waves. The raft covered an area a little larger than San Francisco.

Undoubtedly, a major underwater eruption took place, but it was not possible to immediately determine which volcano was responsible. Using satellite images, scientists have now found a main suspect: Unnamed. Seriously, it's the name of the volcano, at least for now.

This submarine volcano, located near the Tongan Archipelago, made its debut in 2001 with the appearance of a smaller pumice raft in the region. "A rash once, of course. Twice, okay, I think we'd better name you, "said Scott Bryan, a geoscientist at the Queensland University of Technology.

This raft is already moving. It will reach a few islands on the way to the east coast of Australia, perhaps cumbersome harbors and bays, hobbling inside them, annoying fishermen and people just wanting to go from an island to the other. According to Ed Venzke, he will control the volcano database of the Smithsonian Institution's Global Volcanism Program.

This includes boats still in the area. "There was a report that said pumice was backing up in their restrooms," Venzke said. For the most part, however, the raft will be quite harmless to us, surface dwellers.

Volcanism, despite its many benefits, is often perceived as an agent of destruction. In this case, however, "volcanism helps life", said Janine Krippner of the global program on volcanism. Countless marine life forms, from seaweed to molluscs, will do what they always do when objects float in the ocean: grab hold of it and get ready to invade the land that 's gotten. they reach.

According to Venzke, the beginning of the events is not entirely clear, but rumors of volcanic activities at sea began to appear shortly after 7 August. A few days later, boats began to be threatened by pumice.

Rebecca Carey, a volcanologist at the University of Tasmania, said that this part of the world is being watched decently by some satellites. Since satellites can take multiple images a day, scientists can use them to track the evolution of the raft.

"Over there, there's literally a trillion dollars of pumice that make up this raft. And each piece of pumice is a vehicle for an organism. "

Early on, Bryan explained, the raft was compact, with a boat estimating that it was about a foot thick and about 20 to 40 square miles wide. It then cleared up and expanded, covering an area of 58 square miles. An apron of white ash abraded in its wake spread over an area three times larger.

Based on observations from seafarers and satellites, Bryan estimated the oil produced at about 530 million cubic feet. In other words, all these debris would fit into more than 6,000 Olympic decent enough by the standards of all volcanoes.

In the larger order of things, this raft of debris resembling Swiss cheese and consuming boats is a pipsqueak. In 2012, a volcano named Havre, which hid under the waves north of New Zealand, had a colossal upchuck, creating a raft of 155 square kilometers wide.

This Tongan raft fails to make its own weather conditions. A particularly cohesive group of it formed an ephemeral island adorned with its own clouds at one point.

It's unclear how he managed to do that, but Carey explained that the pumice would have cooled down soon after it appeared on the surface of the ocean. This means that these clouds are probably not related to steam. It is possible that the raft has created its own microclimate, but for now, we do not know what is happening.

So where does all this pumice come from? Satellite imagery and some telltale seismicity at the beginning of the raft indicate that it is most likely the unnamed volcano. According to a 2007 sonar study in the area, a volcano was no more than 100 feet below the sea surface, according to the Smithsonian's global volcanism program.

It lies on the Tonga-Kermadec Volcanic Arc, a line of volcanoes, many of which also remain anonymous. The trench, which stretches from the eastern north of New Zealand's North Island to the northern tip of the Tonga Islands, is 1,740 miles long and marks the point where tectonic plates from the Pacific and Australia collide, the Pacific being forced to sink into hellish depths.

It is a very active volcanism area. From the 1970s until today, various pumice rafts have appeared somewhere along this one. Our favorite unnamed volcano is far from isolated; it's a member of a large family that also includes the champion of deep-sea eruptions, Le Havre.

Like many of these rafts, the new pumice ventures westward on the eastern shores of Australia, said Bryan. He thinks that this new ship will make stops in Fiji, Vanuatu and New Caledonia before ending up on the coast of Queensland around April 2021.

It's not that all beach lovers recognize it as pumice: it will be completely covered with life, explained Bryan. "There, there is literally a trillion pieces of pumice stone forming this raft. And each piece of pumice is a vehicle for an organism. "

Millions of molluscs and billions of barnacles and bryozoans – and a ridiculously ridiculous number of algae – will be heading to Queensland in the coming months. It will be a huge influx of biomass. "Every pumice is like its own little island," said Bryan.

In fact, this one is perfectly timed, said Bryan, as he will sweep various islands and reefs by the end of November, just in time for the big coral spawning events. This means that many corals will be brought to the Great Barrier Reef, which has seen better days.

This is not the only reason why the nameless pumice raft is welcome. These rafts also help scientists to detect a new volcanism they would otherwise have completely forgotten, thus giving them a glimpse of the world they rarely have the chance to see.

When it comes to monitoring volcanoes on land, researching and mapping underwater volcanoes, or anything on the seabed, is actually relatively expensive. Even when this happens, seabed mapping does not have the same resolution as the surface world maps.

"We know so little about the seabed," said Jackie Caplan-Auerbach, a seismologist and volcanologist at Western Washington University.

It is often said that 70 or 80% of global volcanism occurs on the sea floor, but this figure is a rough estimate, said Caplan-Auerbach. In fact, we do not know how much volcanism is going on there, but our knowledge of plate tectonics and seabed sounding suggests that it is a lot. Unfortunately, unless we stumble upon it, we are often never trapped.

This may be changing. Increasingly accurate seismometers can sometimes detect a secret eruption, and technology that listens to the sounds of an underwater volcano can be a great way to hear a distant paroxysm. But scientists will not complain when an underwater volcano decides to be a little too rogue and create a life raft over it.

Now all you have to do is give this volcano that is very interested. As he is on the territory of the Kingdom of Tonga, said Carey, it will be up to the kingdom to decide his name.

[ad_2]

Source link