[ad_1]

John T. Consoli / University of Maryland

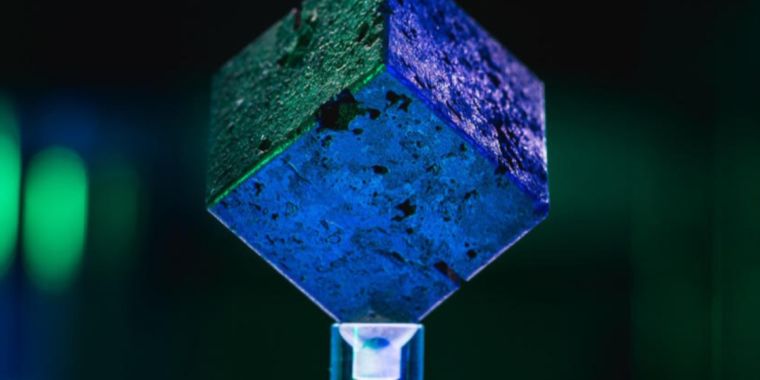

When the physicist at the University of Maryland, Timothy Koeth, received a mysterious heavy metal cube as a birthday present several years ago, he immediately recognized it as one Uranium cubes used by German scientists during the Second World War for the purpose of nuclear reactor. In case of doubt, there was an accompanying note on a piece of paper wrapped around the cube: "Taken from Germany, the nuclear reactor that Hitler was trying to build." Don of Ninninger. "

This is how Koeth's six-year quest began to trace the origins of the cube, as well as several other similar cubes that had found their way across the Atlantic. Koeth and his partner in the quest, Miriam "Mimi" Hiebert, a graduate student, reported on their progress so far in the May issue of Physics today. It's all a tale, filled with top-secret scientific intrigues, a secret Allied mission and even black market dealers eager to hijack the United States on cubes from the United States. uranium in their possession. It is not surprising that Hollywood has expressed the desire to adapt the story to the screen.

Until recently, Koeth was leading the nuclear reactor program at UMD. That's how he met his co-author. Hiebert is completing a Ph.D. in Materials Science and Engineering, specializing in the study of historical materials from museum collections (including glass) and methods used to preserve them, using the reactor facility for the purpose. neutron imaging of some samples. Koeth told her about her research on the origins of her cube, and she began collaborating with him as a side project.

A quest for cubes

Until now, they have found ten cubes in the United States. For example, the Smithsonian Institute had a German uranium cube. "We ended up in a warehouse that looked like the final scene of The adventurers of the lost arch, wooden boxes from floor to ceiling, "said Koeth. And in one of these cases, there was another German cube. "They followed a third cube at Harvard University, where students are regularly introduced to introductory physics courses as curiosities (the cubes are only slightly radioactive and do not pose a health problem, According to Koeth, because uranium is so dense, "He ends up protecting himself," he said, "the radiation you measure comes only from the surface.")

-

The Alsos team dismantles a "uranium machine" in the Haigerloch cave in April 1945. The uranium cubes are in the center, surrounded by graphite.

-

A replica of B-VIII reactor broken down exposed at the Atomkeller museum in Haigerloch, Germany.

-

Close up on the cubes of uranium tied together to form a "looming luster".

Felix Koenig / Wikimedia Commons

In the United States, the Manhattan Project underlined the fear that German scientists under the Nazi regime of Adolf Hitler would pass the Allies under a nuclear bomb. The Germans had a two-year lead, but according to Koeth, "fierce competition over limited resources, bitter interpersonal rivalries and inefficient scientific management" have led to significant delays in their progress towards a sustained nuclear response. German nuclear scientists have been separated into three isolated groups based in Berlin (B), Gottow (G) and Leipzig (L).

Well-known physicist Werner Heisenberg led the Berlin group. As the Allied forces advanced in the winter of 1944, Heisenberg moved his team to a cave under a castle in a small town called Haigerloch, now home to the Atomkeller Museum. It is here that the group built the B-VIII reactor. It looked like a "looming luster", according to Koeth, as it consisted of 664 uranium cubes strung with an airplane cable and then immersed in a heavy tank of graphite-shielded water to avoid any radiation exposure.

While German scientists fought against time, Lieutenant-General Leslie Groves, Manhattan project manager, launched a secret mission called "Alsos", with the express purpose of gathering information and material related to scientific research conducted in Germany. When the Allied forces finally closed their doors, Heisenberg disassembled the B-VIII experiment and buried the uranium cubes in a field, taking essential documents to a latrine. (Pity Samuel Goudsmit, the poor physicist who had to dig them up.) Heisenberg himself escaped on a bicycle, carrying a few cubes in a backpack.

Koeth is interested in physics in general and nuclear physics especially since a young age. "My parents will tell you that they tried to take me to Toys R Us at the age of four and I just cried until we went to Radio." Shack, "he said. When he was eight, an uncle gave him a copy of the seminal story of Richard Rhodes, The manufacture of the atomic bomband a nuclear physicist was born. So, he knew a little about the cubes' story and his first question when he received one as a gift was, "What happened to the other cubes?"

John T. Consoli / University of Maryland

He first assumed that all the cubes of uranium would have been confiscated after the Nazi defeat and sent to the Oak Ridge uranium processing plant in the United States. , to feed an atomic bomb. But a historian told him that in April 1945, the United States had enough raw material and would not have needed additional uranium. He wondered if anyone would have distributed them as souvenirs, perhaps to serve as a clipboard.

There is no trace of cubes entering the United States, but Koeth and Hiebert thought that they might be able to determine if there was a common source for all the recipients of the cubes they followed up to present: a "zero patient" responsible for distribution. their. Koeth's cube came with this note as a clue. It only remained for him to determine who was "Ninninger".

It turned out that the last name had an extra "N." Koeth found a memo from the War Department dated February 24, 1945, stating that "Robert D. Nininger, second lieutenant, had been appointed real estate officer for the Murray Hill area." This area was part of the Manhattan Project's raw materials network. This meant that he was responsible for all the uranium in this part of the network, Koeth said. Nininger proved to be a geologist by training and had even written a book on minerals for atomic energy.

As Heisenberg himself reported, the latest experiment of German scientists failed because the amount of uranium contained in the cubes was insufficient to trigger a sustained nuclear reaction. But Heisenberg was convinced that a "slight increase in his size would have been enough to start the process of producing energy". A model described in a 2009 article confirms it, showing that the group would have needed only 50% more uranium cubes for the project to work.

"If the Germans had pooled their resources rather than divide them, they would have been much closer to creating a functioning reactor."

During their quest, Koeth and Hiebert discovered at the National Archives a box of declassified documents on German uranium and discovered that there were about 400 other cubes of uranium from an experiment. separate reactor made by the Gottow Group. "The combined inventory would have been more than enough to reach criticality in reactor B-VIII," the authors concluded. Germany's secret isolationist approach thus hindered its nuclear program, as both groups did not share information or resources. That said, it might not have changed the course of the war in favor of the Axis powers, because the American project Manhattan was already well advanced.

"Many contributing factors have probably been involved in the resulting sequence of events," write the authors. "Yet the revelation of the existence of additional cubes clearly shows that if the Germans had pooled their resources rather than divided their resources, they would have been much closer to creating a reactor in working order before the end of the war."

For Koeth and Hiebert, the cubes "represent a bygone era of science" and provide a crucial backdrop to this crucial period in the history of physics, as well as other forgotten objects. "Perhaps more importantly, the story of cubes is a lesson in scientific failure, even if it's worth celebrating," they wrote.

DO I: Physics today, 2019. 10.1063 / PT.3.4202 (About DOIs).

[ad_2]

Source link