[ad_1]

YYou may not like it, but your heart is exactly what an advanced endurance machine should look like. And if you do not use this machine, it could have serious consequences for your health, including a heart that looks a bit more like a monkey's.

Human hearts are thin, flexible and able to pump a huge volume of blood – about 2,000 gallons a day. In an analysis published Monday in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciencesa team of scientists says these adaptations have paid off by allowing our ancestors to become prolific hunters, gatherers and runners – benefits that distinguish humans from our grandparents' great apes.

But even today, if we do not use our finely tuned endurance machines, we can literally transform the look and function of our hearts. Robert Shave, Ph.D., co-author of the study and professor of health sciences and exercise at the University of British Columbia, tells reverse ignoring the needs of our heart can trigger the cycle of heart disease.

"We've known for a long time that physical activity, especially endurance physical activity (or cardio), is beneficial to the cardiovascular system, but this study helps to explain why it's this is so, "says Shave. "Diet and stress matter, but an evolutionary perspective helps to explain why the lack of physical activity of endurance makes the cardiovascular system more vulnerable to disease."

Why your heart is made to work

In this study, Shave worked with Daniel Lieberman, Ph.D., an evolutionary biologist at Harvard, and Aaron Baggish, Ph.D., a cardiologist at Massachusetts General Hospital, to examine the evolution of the heart. human. To do this, the team collected data on the hearts of healthy endurance runners, footballers, subsistence farmers and sedentary people. They compared all these hearts to the hearts of chimpanzees and gorillas – our parents of apes with whom we share about 99% and 98% of our DNA, respectively.

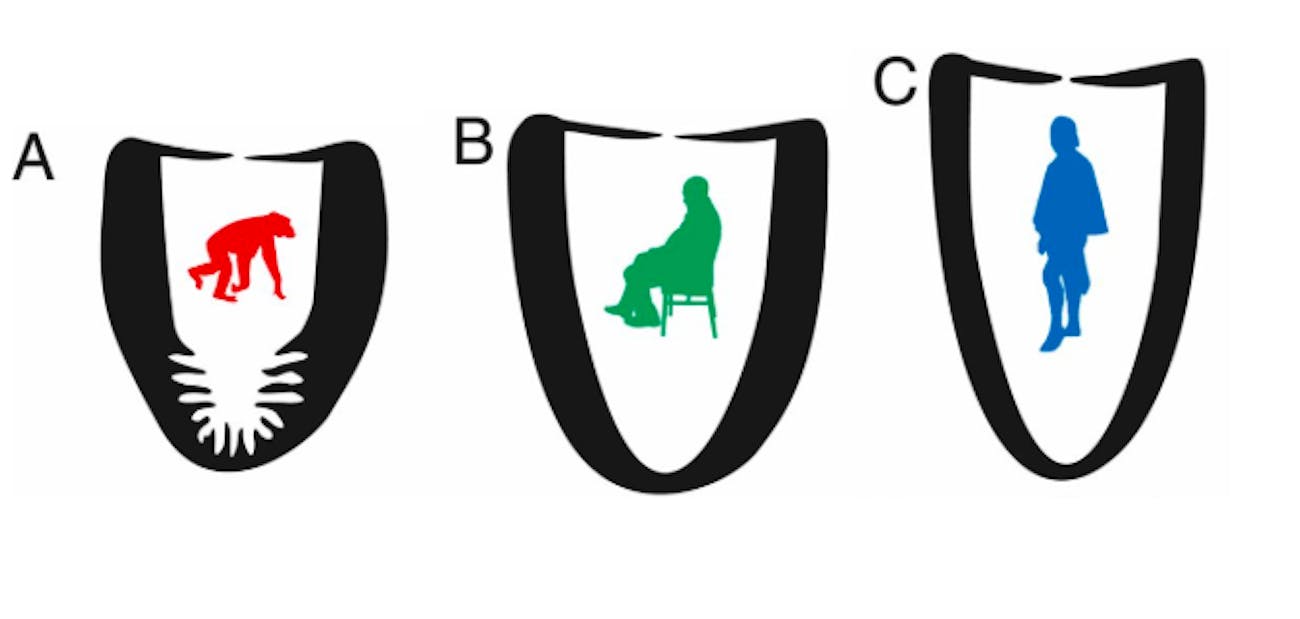

Compared to chimpanzee hearts, human hearts were elongated and slightly thinner. The hearts of the chimpanzees were rounder, thicker and smaller and also filled with trabeculations or folds at the bottom of the left ventricle. Over time, the team suggested that humans had actually lost these trabeculations, allowing our hearts to twist slightly as they filled with blood – a process called apical detorsion.

All together, these adaptations only add one thing: our hearts have become extremely well adapted to fill with abundant amounts of blood, and then pump it efficiently all over the body. This is exactly what your body needs to do during moderate exercise.

Endurance physical activity (aka cardio) is beneficial to the cardiovascular system, but this study helps to explain why it is so … »

Lieberman explains that chimpanzees walk about two to four kilometers a day or perform short periods of intense activity, such as climbing or fighting. But hunter-gatherers, like the first humans, needed stamina to travel enormous distances. Having a heart capable of pumping more blood efficiently would be helpful if you have to cover so much ground:

"Pickers, on the other hand, have to travel long distances every day (9-15 km is the global average), often carrying food and babies. They also spend hours a day digging and performing other tasks of moderate intensity, "adds Lieberman.

In short, the team suggests that exercise has helped turn our hearts into elongated and flexible things that they are today. And still today, cardio continues to play a role in their maintenance.

A heart "monkey"

The endurance exercise seems to be one of the key elements that keep our heart particularly neat Human. And the types of exercise we do (or do not do) can change the appearance of our hearts.

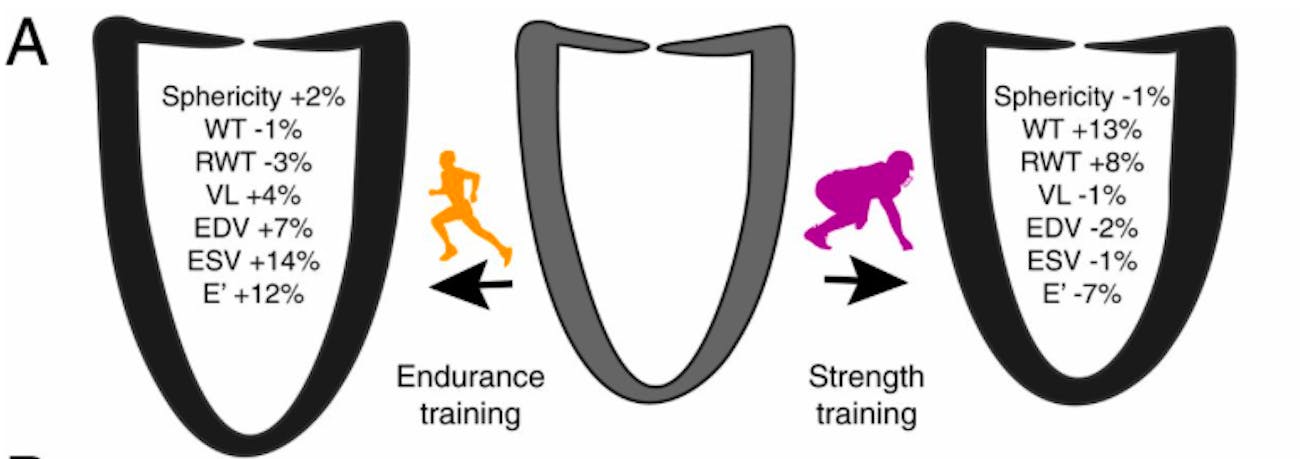

For example, in the sample of football players, the team found that offensive line players who did a lot of strength training and comparatively little endurance training tended to have a thicker, rounder heart. . The endurance runners, on the other hand, had a much more supple and elongated heart.

These two opposite sides of the spectrum evoke the idea that the heart changes physically according to the type of exercise practiced (endurance and endurance). strength training have their advantages). The big idea behind the comparison is that our hearts are malleable. And do not exercise also tends to change our hearts too.

When the team examined healthy and sedentary humans, they found that they tended to have signs of "intermediate phenotype". In short, their hearts began to reshape and develop thicker walls and a rounder shape reminiscent of chimpanzees.

Shave adds that this is important because these changes have been observed in healthy, sedentary adults, suggesting that exercise itself can play a role in helping the heart retain its structure even before it 's. occurrence of conditions such as high blood pressure.

"It is also important to note that sedentary individuals are starting to show signs of remodeling even in the absence of high blood pressure, which highlights the importance of a lifetime activity" said Shave.

Once the thickening has begun, the team proposes. Thickening can lead to high blood pressure, which can lead to even greater remodeling. Over the course of his life, the team writes that this can "lead to" heart disease.

"The findings in this article emphasize not only the importance of exercise with aging, but also about starting and maintaining healthy physical activity habits very early in life." says Baggish. "In essence, the lack of adequate physical activity, even in people [in their] The 20s and 30s seem to confer later health risks. "

The authors add that they will have to test this hypothesis in greater depth. But for now, this highlights the importance of setting up a moderate exercise routine. Your heart is an endurance machine that needs to be used and allowing rusting too long can be a long-term problem.

Abstract:

Chimpanzees and gorillas, when they are not inactive, practice mainly short physical resistance activities (RPAs), such as climbing and fighting, which create pressure stress on the cardiovascular system. On the other hand, to hunt and gather, and then to cultivate, preindustrial human survival is thought to be dependent on moderate endurance life-long physical activity, which creates cardiovascular voluminal stress. Although musculoskeletal and thermoregulatory derived adaptations of EPA in humans have been documented, it is not known if selection has acted in the same way on the heart. To test this hypothesis, we compared the structure and left ventricular (LV) function in semi-wild sanctuary chimpanzees, gorillas, and a sample of humans exposed to very different physical activity patterns. We show that human LV has derived characteristics that help increase cardiac output (CO), thus allowing EPA. However, human VG also demonstrates phenotypic plasticity and, therefore, variability, in a wide range of habitual physical activities. We show that the propensity of human LV to remodel differently in response to chronic pressures or volume stimuli associated with intense RPP and EPA and physical inactivity represents an evolutionary compromise with potential implications for contemporary cardiovascular health. Specifically, human LV exchanged pressure adaptations for volume capabilities and converged to a chimpanzee-like phenotype in response to physical inactivity or sustained pressure loading. Therefore, derived VG and persistent hypotension appear to be partially supported by a regular moderate intensity EPA, whose decline in post-industrial societies probably contributes to the modern epidemic of hypertensive heart disease.

[ad_2]

Source link