[ad_1]

The adventures of Alexander von Humboldt Andrea Wulf and Lillian Melcher Pantheon (2019)

Four years ago, the historian Andrea Wulf saved the Prussian naturalist Alexander von Humboldt (1769-1859) from a relative international obscurity with his charming biography, The invention of nature.

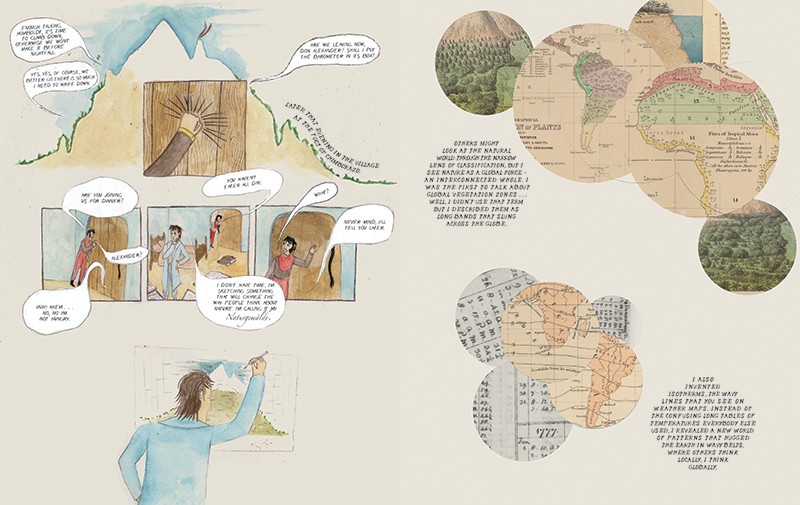

To celebrate the 250th anniversary of Humboldt's birth this year, Wulf partnered with artist Lillian Melcher to create The adventures of Alexander von Humboldt, a non-fiction graphic work describing Humboldt's five years of exploration in Latin America in his youth.

At a time when scientists were obsessed with measuring and documenting all aspects of their environment, human characteristics at the altitude of the hills. But nobody went further in the environmental investigation than Humboldt – and no one thought so seriously about how measurements could be integrated into a global understanding of our globe.

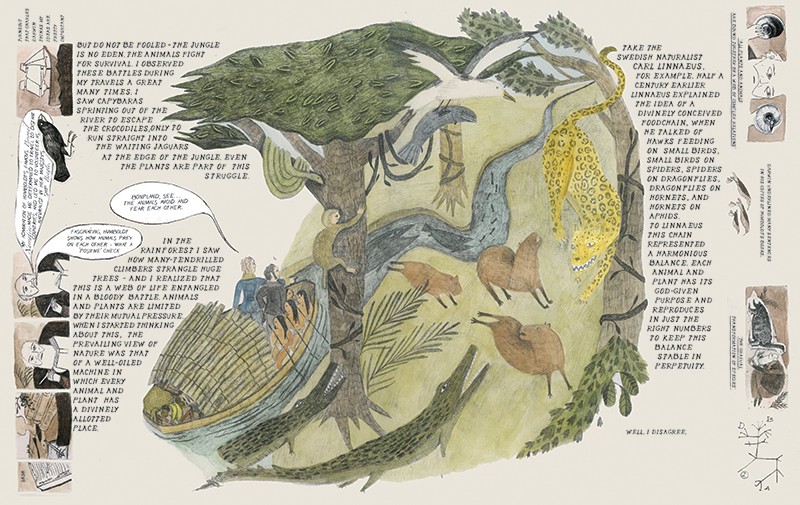

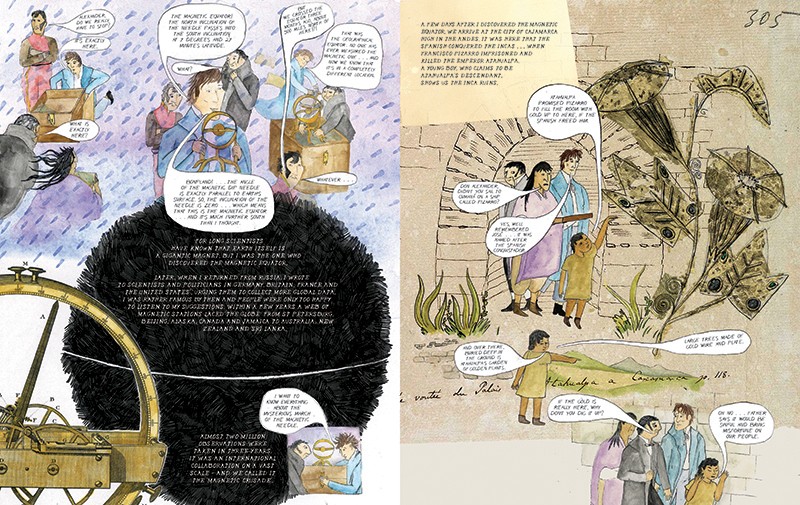

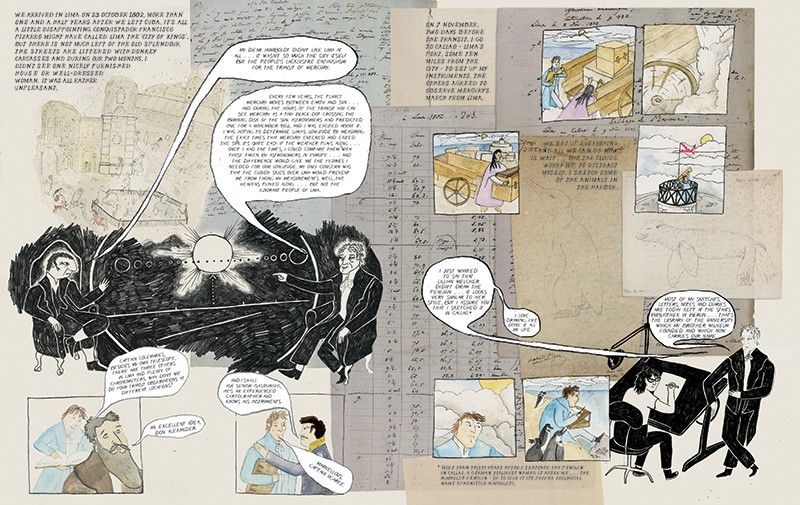

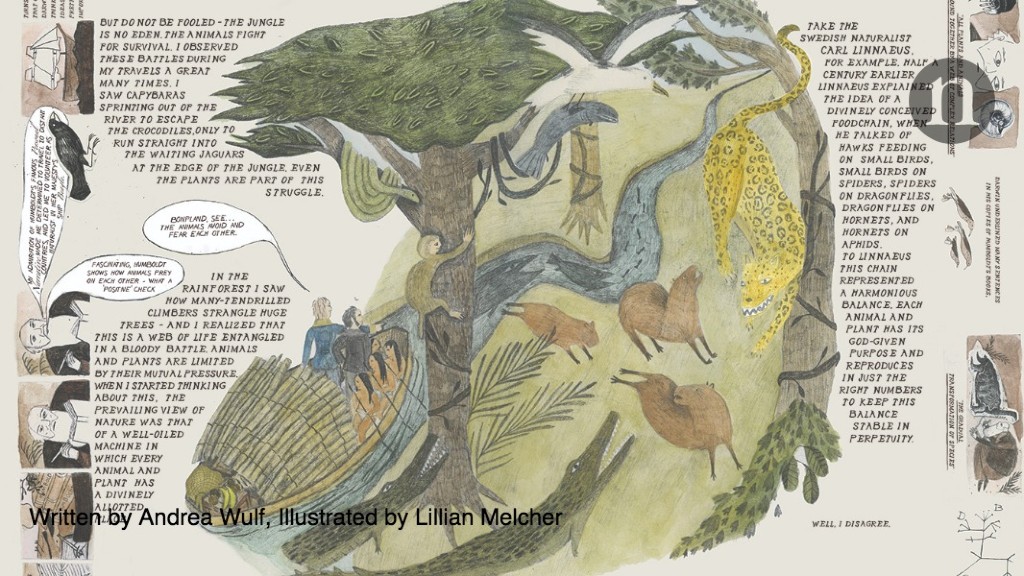

The history of adventure and discovery is well suited to the graphic format, and Wulf and Melcher are proud of it. The informative, light text and inventive illustrations give life to the moronic character of Humboldt, who drags his small group of companions far beyond their comfort zones: burning volcanoes, treacherous mine shafts, along rivers filled of crocodiles, through tropical rainforests covered with mosquitoes.

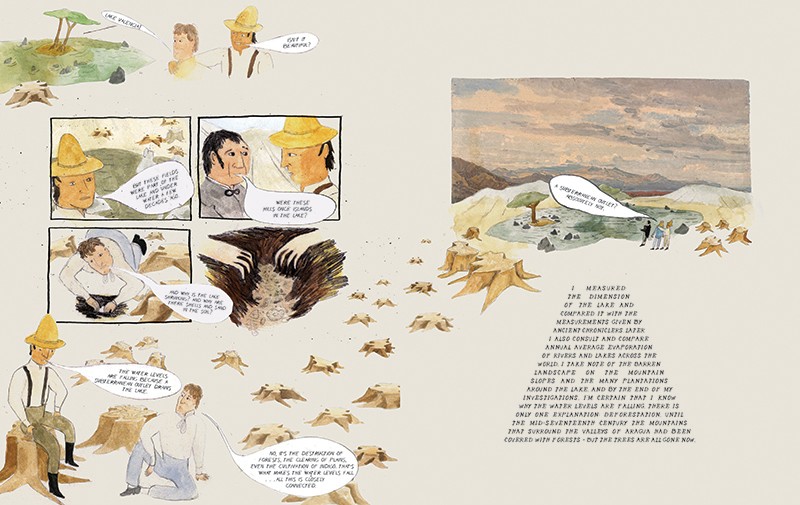

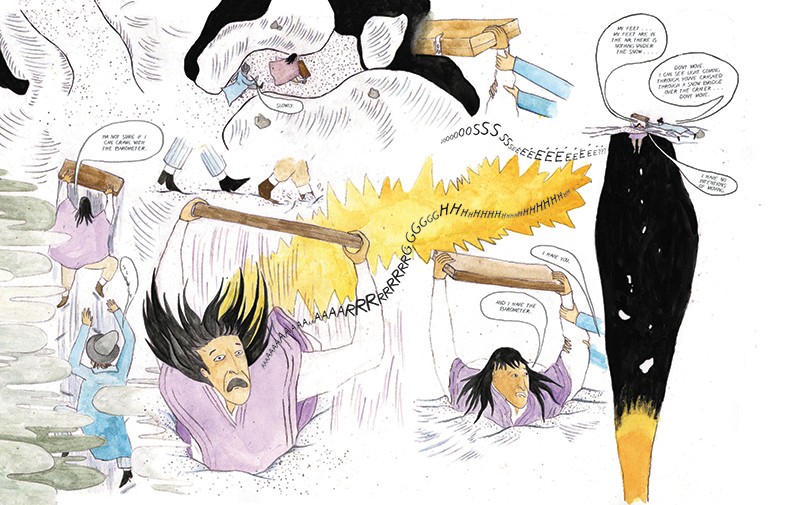

Travelers were equipped with the latest scientific instruments – often resolutely fragile – to measure as many physical parameters as possible. (Humboldt's precious barometer, with its modest supply of spare glass tubes, often appears in the book.) They also took away many notebooks: Humboldt carefully recorded every measurement taken and every species of flora or fauna encountered. Melcher often arranges his illustrations into collage compositions using pages from these notebooks.

As you read Humboldt's extraordinary achievements, you wonder how he may have been so forgotten outside of Germany. His appetite for knowledge was voracious and he left nothing – not even a personal danger – to obstruct the collection of data on all aspects of the natural world.

His ability to synthesize knowledge was equally vast, which allowed him to develop his main theory that everything in nature is connected (it is concretized in his massive book of 1845-1862). Cosmos; see A. Abbott Nature 431631; 2004). Disrupting any element of the nature giant, be it a local species or climate, will have repercussions, he said. In particular, he warned that deforestation could harm the climate and the environment, as forests humidify and cool the atmosphere and prevent soil erosion.

He was friends with other intellectual giants of his time, including the polymath Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, and Charles Darwin recognized his intellectual debt to Humboldt. Numerous phenomena bear its name, from the Humboldt Current along the west coast of South America to the majestic Humboldt Peak in the Colorado Rocky Mountains. Many plant and animal species also bear his name – and many German cities have a Humboldtstrasse.

Humboldt was a liberal who had opposed slavery. He was a motivated and highly focused scientist. He was a man of almost infinite self-confidence. The adventures of Alexander von Humboldt offers a great way to get to know him.

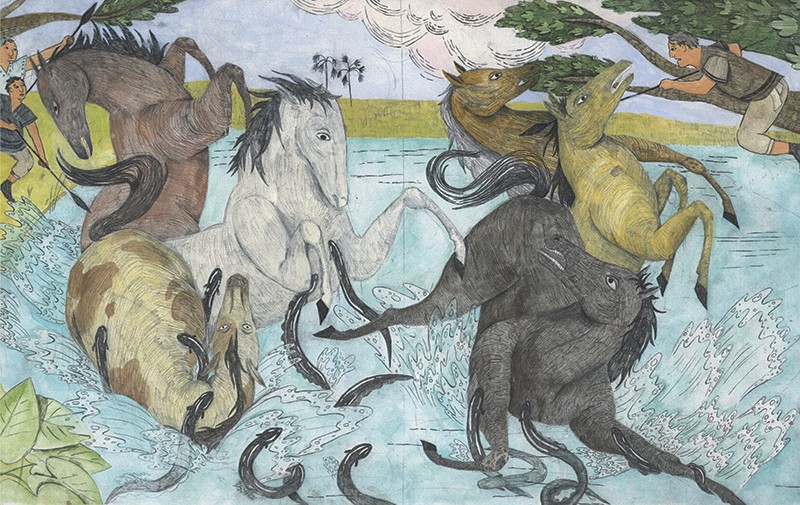

In the Amazon, indigenous peoples showed him how they used horses to catch electric eels (Electrophorus electricus). Humboldt then used the fish in experiments (including some on himself) to understand the particular properties that allowed them to stun prey and predators with electric shocks.

Combining his own observations with known information, he concluded that the Valencia Lake in Venezuela was decreasing as the surrounding forests had been cleared.

He challenged the view of Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus that a divine plan kept nature in a harmonious balance. Humboldt has observed that nature is much more brutal than that.

His explorations put him in danger, as well as his less intrepid companions, but he is still concerned about his instruments.

He invented the isotherms, the wavy lines – which are now well known weather maps – that connect regions of the world where the temperature is the same.

He discovered the position of the Earth's magnetic equator.

He observed the passage of Mercury from 1802 through the Sun in 1802, which allowed him to calculate the longitude of Lima.

Sign up for the everyday Nature Briefing email

Stay informed about what matters in science and why hand-picked from Nature and other publications around the world.

S & # 39; register

[ad_2]

Source link