[ad_1]

Alzheimer's disease is one of the most feared diagnoses, and fear is especially acute in the elderly. This complex brain disorder, which usually affects the elderly, can lead to many cognitive disorders, including memory problems.

About 5.7 million Americans live with Alzheimer's disease. In addition, millions of loved ones and caregivers are affected, according to some estimates there would be up to 16 million unpaid caregivers.

As the baby boom generation begins to turn 65, the number of people diagnosed with this disease is expected to continue to rise.

The available medications do not help much in managing memory problems and associated behavioral changes. There is a clear need for more effective treatment options.

In response to this request, a group of researchers tested the use of deep brain stimulation to improve the memory and cognition of people with Alzheimer's disease (Trial ADvance). Although the long-term benefits for memory have not been as robust as expected, nearly half of patients reported recalling past experiences. This is a notable observation because it has occurred in people with memory problems. In addition, it can help researchers better understand how memory is formed and retrieved.

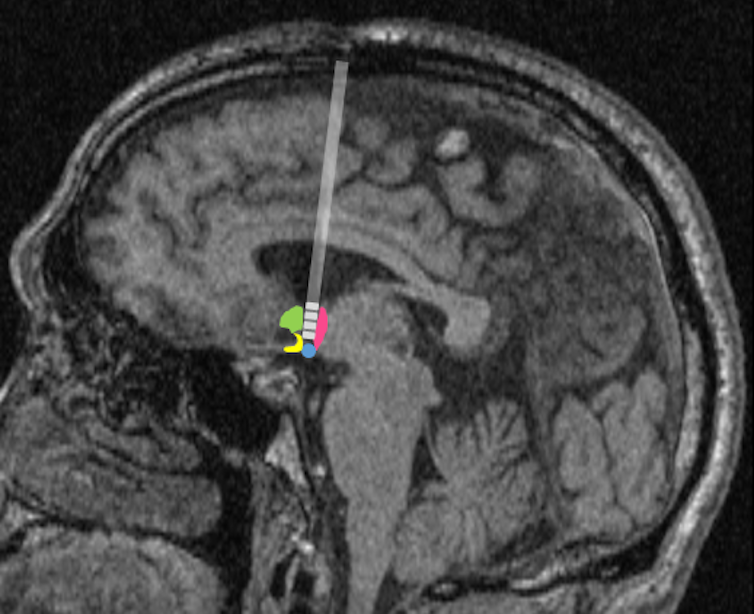

Deep brain stimulation for Alzheimer's disease

Wissam Deeb, CC BY-SA

Deep brain stimulation is an FDA approved treatment for many neurological conditions such as Parkinson's disease. It involves implanting stimulating electrodes through the skull, with electrical wires, into deep structures of the brain. These electrodes are then connected to pacemaker devices located in the patient's chest. Pacemakers produce an electrical signal that alters brain activity and improves targeted symptoms, such as tremors in Parkinson's disease.

In Alzheimer's disease, the circuits of memory in the brain, which include a remarkable structure called fornix, are affected. Fornix is important for remembering events and personal concepts. In the ADvance trial, the researchers evaluated whether deep brain stimulation at the fornix level improved the memory of 42 subjects with Alzheimer's disease. They found a possible improvement in memory among the over 65s; the researchers saw no benefit in evaluating all participants. Learning from this experience, researchers embark on another trial called ADvance II.

But there is more in the story

Recently, researchers involved in the trial and myself wrote an article for the New England Journal of Medicine that analyzes an interesting observation from the essay: About half of the subjects spontaneously said they remembered intense memories. These were detailed and unsolicited memories of their past. These memories only appeared for a short time and their presence did not translate into an improvement in long-term memory. A key point to remember is that deep fornix brain stimulation can induce memories, at least briefly, although the implications for treatment and long-term effects remain unclear.

Of the 42 subjects who participated in the ADvance trial, 20 described past events during the first assessment session of their deep brain stimulation for potential side effects. During these assessment sessions, the intensity and location of the stimulation were varied to determine the optimal parameters.

Analyzing the data from the first trial, we counted 85 unique memories in memory more or less detailed. Twenty-nine memories had detailed details about the place and time of these memories. For example, one person reported having spent a holiday in Aruba, including the taste of lime in the margarita and his feeling of "buzzing". Some memories go back decades.

These were memories that participants had not thought about for many years and that had a lot of emotional value. I found it interesting that increasing the intensity of deep brain stimulation increased the detail of memories. The details were limited only by the appearance of undesirable side effects related to more intense stimulation of deep brain stimulation. For example, one person originally described a generic memory of "helping a guy find something on his property" that then evolved, as the intensity of the stimulation increased, remembering that it was a good thing. was the night around Halloween, and that he was with his son. .

The 20 subjects who developed these memories when deep brain stimulation was activated did not do better than those who did not have cognitive tests. In addition, there was no association between these memories or their intensity and cognitive and memory outcomes. Therefore, the implications of these results for treatment remain unclear.

Despite these limitations, these results offer some ideas. First, they add to accumulated knowledge about areas of the brain involved in memory, including the brain of people with memory impairment. Secondly, they reveal that it is possible, albeit perhaps only temporarily, for people with Alzheimer's disease to access memories stored with electrical stimulation that we had not had. access previously, probably because of brain changes associated with the disease.

Further work and research is needed to clarify the role of these electrically induced memories. Do they last long after the implantation of deep brain stimulation? How to induce different memories? Why only half of the subjects have developed such memories? How can researchers use these memories to develop deep brain stimulation and other treatments for Alzheimer's disease?

This work provides a better understanding of the effect of electrical stimulation in the fornix region in people with Alzheimer's disease. It also provides additional information in the scientific quest to treat this disease. And as part of the study of Alzheimer's disease, any new information that may be useful is good news.

[[[[Deep knowledge, daily. Sign up for The Conversation newsletter. ]![]()

Wissam Deeb, Assistant Professor of Neurology, University of Florida

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

[ad_2]

Source link