[ad_1]

Sudanese Islamic burial sites are not located at random as has traditionally been believed. Rather the opposite. Using satellite technology, it has been discovered that contrary to the belief that these Islamic burials were scattered haphazardly across the ancient landscape, thousands of burial sites follow a “galaxy-like” pattern of distribution.

Knowing this audience, I know I can safely open this story with the deeply Gnostic statement: “As above, so below. I am sure that a large majority of you will understand the implications associated with this concept, and by the end of this article it will become perfectly clear why I have chosen this phrase to represent the results of a new published study. in the open access journal. PLOS ONE by Stefano Costanzo from the University of Naples “L’Orientale”.

Islamic funeral qubbas scattered around Jebel Maman in Sudan. (Costanzo et al. / PLOS ONE )

Discover the galactic distribution model of Islamic tombs and burials

The Kassala region in eastern Sudan is home to a wide range of funerary monuments that date back thousands of years to the Islamic tombs of the modern Beja people. Sudanese Islamic burial sites are found scattered in patches throughout the region known as Jebel Maman and until now it was assumed that they were located at random. However, the new study shows that they were distributed based on large-scale environmental factors and small-scale social factors, creating what is described as “a galaxy-like distribution pattern.”

According to a report in Live Science Professor Costanzo said archaeologists suspected that the location of these monuments was most likely influenced by geological and social factors. Based on this premise, the researcher set out to unravel all the underlying models within the ancient funerary landscape. His goal? Provide new information on the “ancient cultural practices of the people who built them,” according to the new document.

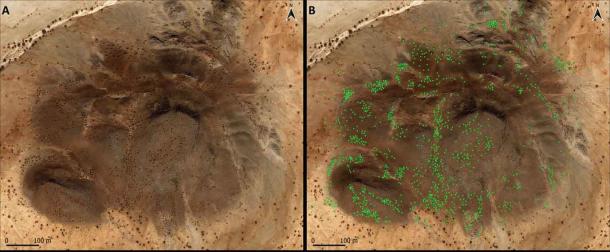

Satellite imagery showing 1,195 qubbas, or Islamic burials, around and above a small rocky outcrop. (Costanzo et al. / PLOS ONE )

The above and the below: using satellite imagery to find patterns

Getting back to “As above, so below.” In this new study, Costanzo and his team used remote sensing satellite images to trace the location of 10,000 grave monuments over 4,000 km2 (1,544 square miles). To analyze the data set, they adopted a “Neyman-Scott cluster model” that was originally developed to study spatial patterns within the cluster of stars and galaxies.

Thanks to this new application, it has been revealed that, just as the stars cluster around the centers of high gravity, the burial monuments of Kassala cluster by the hundreds around the central “parent” points. Researchers believe that these parent points themselves likely represent older graves of regional significance.

What then made certain sites become parent points, or central regional sites of importance, compared to others? The authors hypothesize that the environment greatly influenced the larger-scale distribution of the graves. The so-called “high density” areas focus on areas with “favorable landscapes and available building materials,” according to the newspaper.

They also determined that the smaller-scale distribution was more of a “social phenomenon” and that the graves surrounded older or significant central burial structures. Did you notice that I still haven’t answered that last question that I asked myself? Let us ask it differently. Why then were some burial sites more important than others, so much so that they became “parent” points in the new study?

An example of a buttress burial mound in the Kassala region of eastern Sudan, which are simple raised stone structures that were prevalent throughout prehistoric times and African history. (Costanzo et al. / PLOS ONE )

The dawn of cosmo-archeology

The answer to “why” some burial sites have become more important remains unanswered. However, it is suspected that more recent family burials may have caused more intense clustering, or that the predominance of burials is increasing around older burials of traditional significance. What is perhaps a greater discovery than the new fact that Sudanese Islamic burial sites are not randomly distributed is that for the first time, archaeologists have applied “advanced geospatial analysis” to uncover them. environmental and societal influences underlying the burial landscape of ancient eastern Sudan.

Essentially, what happened here was a change of resolution, and this change revealed some old hidden secrets. Standing at any cluster of burial sites looking across the horizontal plane, the minds of archaeologists have only a fraction of the spatial data needed to appreciate the underlying distribution patterns. By using satellites, a whole new dimension was reached, and thus clusters were identified. Thus, the new study represents the first time that a cosmological approach has been applied to an archaeological problem in this way.

This means that the more our measurement technologies improve, the more we realize that in our universe, which is above , is really reflected below. And on a more immediate level, the use of satellite technology in archeology to verify that ancient burial mounds and Islamic burials cluster like stars in distant galaxies around central sites, represents the dawn of a whole new approach to explore our ancient origins.

Top image: A panoramic view of the qubba tombs, a type of burial tomb or Islamic shrine, around an area known as Jebel Maman. (Costanzo et al. / CC-BY 4.0 )

By Ashley Cowie

[ad_2]

Source link